Deborah Merola, PhD, is an American theatre director. She first came to Nepal in 1992 and later as a Fulbright scholar in 2003 and 2011. Under the Fulbright programme in 2011, she also worked with Gurukul Theatre in Kathmandu and produced a play, Desire Under the Elms. Even after nine months of the programme, she chose to stay in Kathmandu and began teaching drama at Tribhuvan and Pokhara universities. Also, Merola established One World Theatre, a company that has produced and performed over 30 plays in Nepal, mostly in English and some in Nepali. Over these years, she worked with stars of Nepali theatres and films such as Bipin Karki, Namrataa Shrestha, and Rajkumar Pudasaini.

Merola was preparing for a play to stage in Kathmandu in March 2020 when fears of the Covid-19 pandemic gripped the country. She closed her production and moved back to the US and hopes to return to Kathmandu later this year. As people are gradually returning to normality, the veteran director is hopeful of the revival of Nepali theatre soon.

Onlinekhabar recently talked to Deborah Merola on the past, present, and the future of the Nepali theatre. Excerpts:

You said you closed a production 10 days before its opening last year. How did you feel when you took that harsh decision?

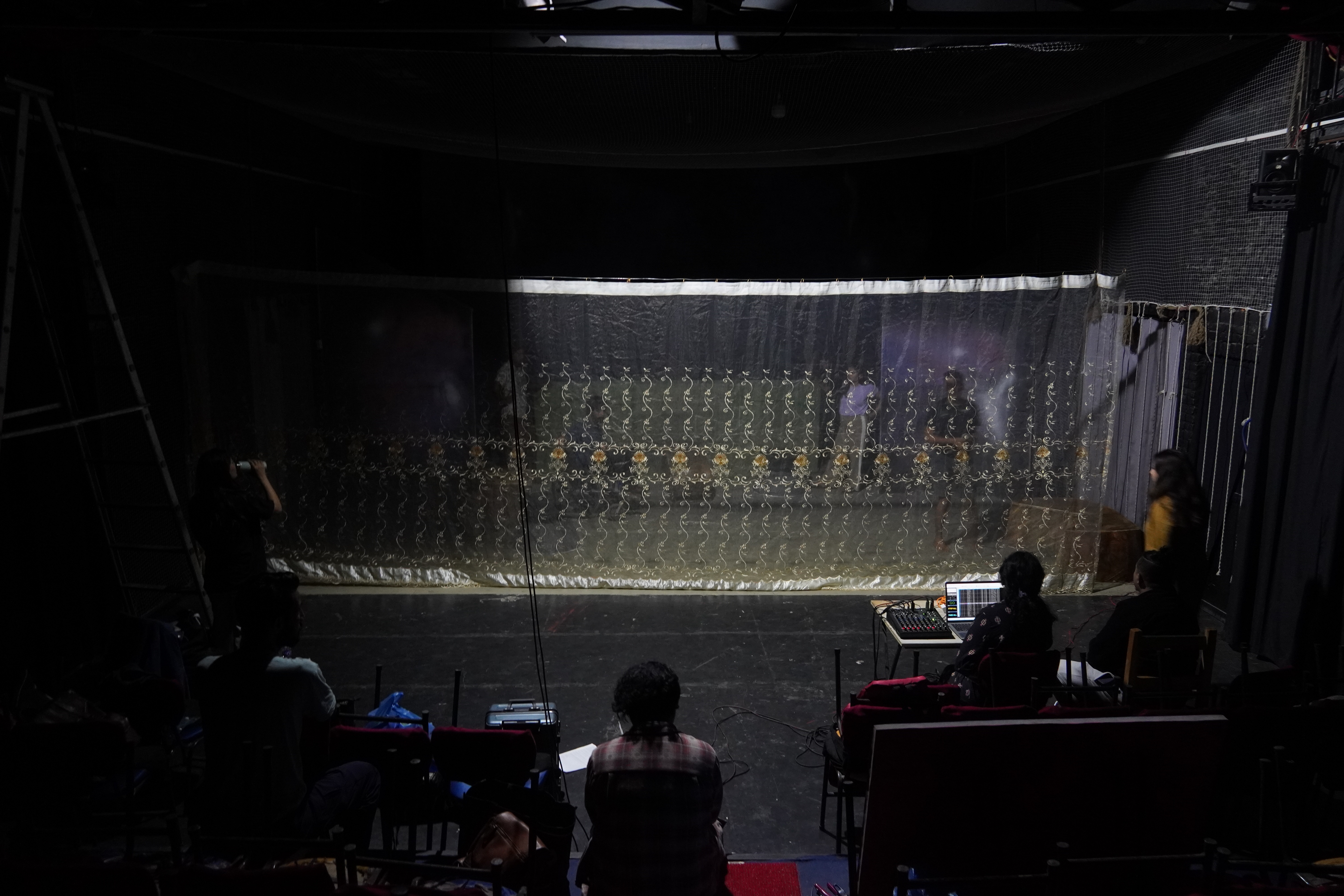

Our promising remaining theatre season had to be cancelled or postponed because of Covid-19. The Ride Across Lake Constance by Nobel Laureate Peter Handke was proving to be a truly funny and thrilling ride, but we shut it down only ten days from our scheduled opening on March 13, 2020. We paid the cast two-thirds of their salary to help them through the coming difficult period, which was difficult indeed, with all theatres closed.

Now, we plan to perform The Ride Across Lake Constance on September 10 to September 19, 2021, on the occasion of our tenth anniversary, in the outdoor courtyard of Barbermahal Revisited, allowing for social distancing.

So, it seems Nepali theatres were seriously hit by the Covid-19 pandemic, doesn’t it?

Like so much in life, benefits and disadvantages can balance out. We do not own our own theatre but do not carry overhead. One World Theatre is really an international theatre company—in 2019 we had two directors from the USA (Rose Schweitz and me), one from France (Alize Biannic), one from Belgium (Bruno Deceukelier), and two Nepali directors in the Nepali language plays (Rajkumar Pudasaini and Sandesh Shrestha). Our plays that year originated or were centred in Argentina, India, Nepal, and the USA.

The Westerners in our company do not count on OWT for their livelihood and therefore could weather the theatre closures more easily than our Nepali partners who were really suffering. In our 2018-2019 theatre season, we produced eight full-length productions, including four original dramas and employed over 120 Nepalis, several more than once. When the 2020 season was cancelled mid-March, all the paid work for Nepali artists was cancelled too. In addition, we all suffered from the loss of our shared creativity.

I know about the impact of Covid-19 primarily through One World Theatre artists who have had a very difficult time. Although we always pay our artists at a rate that compares—even favourably compares—to other theatres, even in ordinary times, the OWT artists need to supplement the income from production budgets by acting in other theatres, doing voiceovers, and making films. Most of those regular outlets are now also closed due to Covid-19 except for some Zoom teaching sessions.

How do you compare it with the Covid-19 impact on the theatres worldwide?

I think theatres in the West have more and better technical capacity for virtual productions, with their artists, too, better prepared to work remotely. Some Western theatres are producing quite advanced digital collaborations and live-streaming. But, it is a hard adjustment for all since much of the spontaneity, creativity and joy comes from doing live theatre and connecting with an audience.

But, don’t you think Nepali drama scene was already facing a great disaster even before the pandemic? The audiences were scarce and theatre companies were opening and closing one after another.

This was not my experience, although as a non-Nepali speaker, very busy with producing English language dramas at One World Theatre, my experience is limited. Although Gurukul faltered and Theatre Village closed, established theatre companies continued to present excellent dramas: the faithful social justice productions at Sarwanam, Sabine Lehman’s well-attended annual productions at Studio 7, and Anup Baral’s Actor’s Studio that brought the advanced director training from Indian National School of Drama as had Sunil Pokharel and Bimal Subedi. In its own right, One World Theatre entered into very active production of iconic and experimental Western dramas and original plays, often in Nepali.

The artists at Mandala Theatre built their own theatre, which became a new centre, consistently able to attract large audiences of mainly young people. Ghimire Yuba Raj oversaw the building of Shilpi Theatre with commedia dell’arte training and a Shaili was successful in organising children’s theatre festivals. There was the Theatre Mall too, focusing on children. More recently, Kausi Theatre has emerged as a centre for women-centric drama and Sulakchhyan Bharati is just opening Purano Ghar. International theatre festivals in Kathmandu and Theatre Hub encourage cooperation among our amazing theatre community.

Several of these theatres have offered excellent actor training programmes, although sadly, there is often not enough quality productions happening for these young artists to make a living.

But, I think it is a good thing that young artists are filling the gap, creating their own theatres, putting on dramas, and learning by doing, even if their fledgeling theatres fail. It reminds of the 60s in the USA or even the early days of Hollywood when making a drama or a film was not prohibitively expensive (hence, not financially lucrative) or regulated. Until Covid-19 brought all this creative activity to a halt, albeit a temporary one, the theatre was experiencing a renaissance in Nepal, with the number of offered productions easily able to fill theatre festivals.

Not all of these productions were of the same calibre, and contemporary playwriting in Nepali, or in English on Nepali themes, is needed. We look to our theatre to give us back an understanding of ourselves, our history, politics and culture, and communicate these insights across other cultures. In the United States, the dramas of Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, August Wilson, Tony Kushner, Suzan-Lori Parks, etc are part of our national heritage. In addition to religious and historical dramas, Nepal deserves a contemporary reflection of its culture, adding to its own national treasury.

But, I am no expert on Nepali theatre. For the five years after the founding of One World Theatre in 2011, I lived in Nepal and began to see productions in Nepali in an ever-growing number of theatres. The old Theatre Village where we rented theatre space was our focal point in those years. Likewise, Gurukul was the centre of the theatre world, complemented by a few other venerable theatre companies.

Yes, perhaps the best recent time Nepali theatre has ever got in Nepal was during the 2000s when Sunil Pokharel’s Gurukul was dominant in Kathmandu. You also worked with the Gurukul team. Why do you think no successor could replace the vacuum created by Gurukul’s absence in Kathmandu? Or, was this institute overrated?

I think Sunil Pokharel is a gifted actor and director, and a guru to many. But, like other companies or enterprises based on the brilliance of a single individual, this has inbuilt limitations. I did have the privilege to work with the Gurukul Theatre Company on Desire Under the Elms and later brought productions to the international theatre festivals it hosted.

I think Gurukul’s combination of a physical theatre where the actors lived and worked together and ran the theatre, engaged in continual training workshops and alternating in large and small roles, was extraordinary and the true model for a repertory theatre, which Mandala somewhat follows. One World Theatre was the tremendous beneficiary of this time, with built friendships with actors, most particularly Rajkumar Pudasaini, the finest actor I ever directed in my history of 75 productions in the States and Nepal.

But again, don’t you think theatres are losing their powers just because there are better mediums to express, communicate, and get entertained? For example, people have also stopped going to cinema halls because the films are already on the TV at home. The internet gives you everything.

This is a usual question: how can theatre, and film, survive? While the internet appears to give us everything, its content is often from the West and filtered through commercial exigencies, not ideal for Nepal. Also, the writers, directors, actors, and designers that produce these shows, need training. On TV platforms, we often see predictable plots and gratuitous violence and sex, although there are also some beautifully produced shows. On Netflix, I just saw One Night in Miami and the depth of its analysis and the power of its text came from the stage play on which it was based.

So, what needs to be done to revive the Nepali theatre?

In my opinion, the current pause is a temporary one in the on-going renaissance of Nepali theatre that once it begins, it will hopefully rebound. I see a new spirit of cooperation between theatres and new productions launched in the past weeks. This drive should get back its momentum soon given the amazing talent and devotion of its theatre artists.

For this, Nepal also deserves a national programme like the National School of Theatre in India, which supports multilingual and indigenous theatre throughout the country, and produces high-quality world drama. A BA/BFA Theatre Programme at Nepal colleges, and then a MA/MFA and PhD programme at a university could provide education, training and employment to theatre academics and artists.

Likewise, the theatre community needs to access the tourists visiting the country. There are many foreigners who visit Nepal and tell me they do not know if there is any theatre in Kathmandu. Further, until world governments view art as development, the theatre will not be the powerful educational and economic tool it can be.

Anything that the Nepali theatre can learn from the international experience, especially on resisting modern technology and asserting its presence in hard times?

Most theatre artists, especially at a high professional level, are not resisting but embracing modern technology, while also being able to function with very simple means. The human body, voice and soul are the essential elements of our craft in communication with other human souls.