Of late, respecting diversity has been one of the key topics of social discussions in Nepal. With this topic comes the idea of respecting and promoting different mother languages. Some efforts have been made to this end, for example by the Kathmandu metropolitan city that has implemented a Nepal Bhasa course up to the eighth grade. While the move has been appreciated by many, it has faced some questions too.

Amrit Yonjan-Tamang is an advocate for education in mother languages in Nepal. As a language expert, Tamang has served three terms at the Curriculum Development Centre under the Ministry of Education. Tamang has been a leading advocate for the promotion and preservation of the Tamang language and has recently led the opening of the Tamang National Library at Tamang Bhawan, Boudhha, Kathmandu.

Tamang observes that learning the mother language is an important part of a child’s development. But, as the world observes International Mother Language Day and UNESCO observes International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022-2032), he hopes that Nepal will also stride forward to preserve the diverse languages and not just a few selected ones, paving way for multilingual education. He talked to Onlinekhabar about the status and importance of the mother language, and mother language education in particular, in Nepal. Excerpts:

Let’s begin the conversation with your mother language. What is the status of the Tamang-speaking population in Nepal? What changes do you expect in the new census results?

If we go by according to the 2011 census data, the share of Tamang speakers was 5.11 per cent of the total population. Within the community, it was some 90 per cent who knew and spoke their mother language.

As for the new data in the census conducted last year, the number of Tamang speakers will not justify the reality, so we are not sure about the data. I say this because the census form has a section for the ‘purkhyauli bhasa’ (the language of the ancestors). The form was curated in such a way that it would bring forward the Sanskrit language as intended by some of the lobbyists. Before the census was conducted, we sat with the Central Bureau of Statistics team multiple times and tried to change this as Sanskrit does not qualify as a first language but rather a classical language. However, we did not succeed.

Meanwhile, we also have lobbied from our side and informed the community to write Tamang, both in the ancestor and mother language columns. So, we are not confident about the true number the census will show. But Tamang and Limbu are two communities that have been successful to retain their mother language most strongly, so we are hopeful.

Why is identifying one’s mother tongue in the census important?

The census is considered the national data and the national policies are made based on that. When we identify our mother tongue, it gives the policymakers a base to formulate the plans. There is no alternative to the census conducted by the CBS. If even other organisations try, they cannot replicate the task and there will always be a gap in the number; we may not get the true number.

If there is any community that has over 10 per cent population count, they are included or prioritised in policy-making, so it is important to participate in the census.

What are some of the key developments made for the promotion and retention of the Tamang as a key mother language in Nepal?

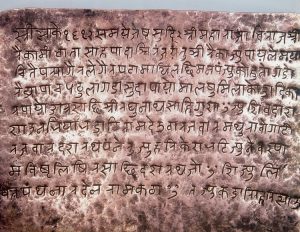

Tamang literature is a rather new one. It started in 1957 with Buddhiman Moktan’s book ‘Jikten Tamchhyoee’ or Tamang Vanshavali. Since then, there have been over 200 books including Brihat Tamang Shabdakosh (comprehensive Tamang dictionary). Apart from that, many poems, novels, stories, epics have also been published.

The community has got help from the media too in the promotion of the language. Radio Nepal in 1994 gave a five-minute slot to Tamang news which has been consistent to this day. There have been many news media portals run by the members of the community which have promoted the language.

Meanwhile, research about the language started in 1847/8. After that, many people have done their dissertations about the Tamang language, and they have helped the community learn more about itself. Teaching in the Tamang language has also been going on in some 400 schools all over the nation.

We are seeing that more and more people are forgetting or not feeling comfortable conversing in their mother language. Do you also observe the same? What do you think are the reasons?

Over the ten years, the new generation that moved to the cities has been more influenced by English and Nepali languages. Many have also migrated abroad for work and study reasons. In both situations, English and Nepali as peripheral or official language has more coverage or use in people’s lives.

The new generation learning their mother tongue is credited to the older generation, passing on the knowledge. But, parents are busy working or have migrated to cities and Gulf countries while the young generation is moving to developed countries for study and work. So neither of the generations is getting the time to learn and practise their mother languages.

So it has opened many gaps, because of which we have seen a great loss in the number of people speaking in their mother languages. In a way, Nepal has been unsafe and preservation of the language has been a challenge.

Multiple efforts have been made to preserve and promote mother tongues in Nepal, including social activism and curriculum development. How do you observe the development?

In the Kathmandu valley, there have been multiple efforts regarding the preservation and promotion of Nepal Bhasa, including its recent adoption in the school-level curriculum. It is natural because the community has seen some 35 per cent loss of language.

But, other languages including the Tamang language have not seen that level of activism. However, from our side, we are continuing to advocate for the community. Along with that, we are supporting and getting ourselves involved in the Language Commission.

Meanwhile, including Nepal Bhasa in the school curriculum is one thing; imposing the language on all is completely unfair and unconstitutional. There are 101 languages spoken in the valley and every child has the right to study in their mother tongue, but children are forced to study Nepal Bhasa. The way the curriculum has been designed is also unsystematic and not at all in the way the multilingual education that the constitution promotes.

Rather than choosing Nepal Bhasa as a medium of instruction, an approach should have been taken to teach the language. The content being taught can be learned in any other language, so its longevity is not confirmed.