The 2015 earthquake in Nepal shook the heart of Wolfgang Korn miles away. Yet, after some months, the German architect was a bit happy and proud that he could help in the reconstruction process of four monuments in the Kathmandu valley.

“Those four monuments could be rebuilt as my sketches helped them scale the dimensions in the initial phase although my sketches were not the only factors,” says Korn about the reconstruction of monuments of Maju Dega, Kasthamandap, and Char Narayan of Kathmandu and the Vatsala Temple of Bhaktapur.

In his 20s, Wolfgang Korn wanted to travel to West Africa, but destiny had other plans for him. Hence, without any expectation, he first visited Nepal in 1968 when he was 25 as a part of the German Development Service project.

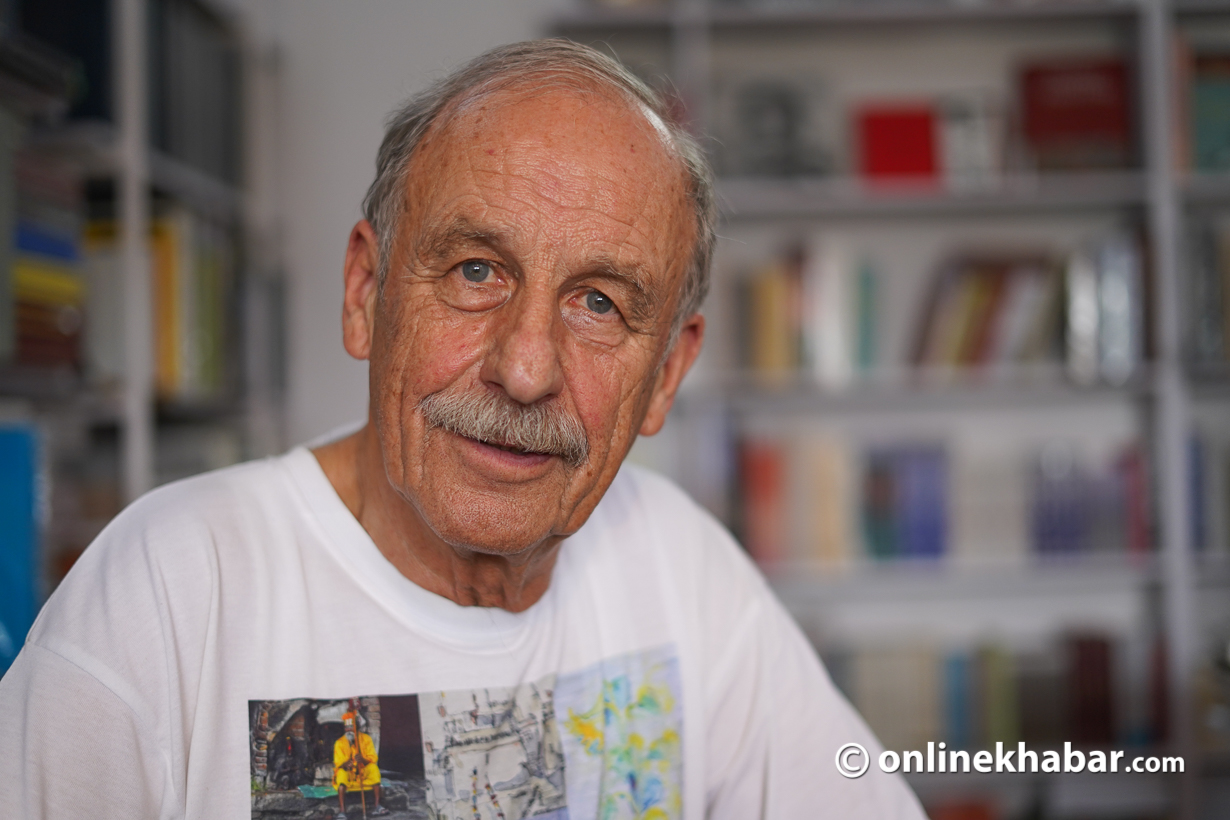

He is currently in his late 70s and still actively disseminating knowledge about traditional Nepali architecture to Nepali people. He has written four books about Nepali architecture—Traditional Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley, Lichhavi Chaityas in Kathmandu-Tal, The Buddhist Monasteries of Muang Sin and Erotic Carving of the Kathmandu Valley Found on Struts of Newar Temples—so far.

Renewing the old ties, he was sent to Nepal by the Senior Expert Service in Germany in 2013. The service sends some specialists contributing their skills during their young age to other countries, but only upon host countries’ request.

From his mid-20s to the late 70s, Wolfgang Korn studied a lot about Nepali culture and architecture, in particular those related to the Newa people of Kathmandu. The zeal he shows while talking about Nepal embodies the love and appreciation he has for the culture-rich Himalayan country.

Passion for Newa architecture

Wolfgang Korn finds the Newa architecture fascinating and gets amazed by the building technology Newa people have.

“The Newa architecture is not only impressive but also unique. I don’t know any building culture that is so highly developed in a very small place,” the scholar says, “Normally, in China or Europe, Germany or America, large areas of a country are living the same way, buildings are in the same way. Here, it is original and particular development patterns have not been copied.”

“I am very much amazed on how it is possible to make such construction only using two components—mud and timber,” exclaims Korn.

His passion for understanding Newa architecture grew as he stayed here and worked. “It was a bit difficult for me. When I came here in 1968, I did not know any history of Nepal or Nepali architecture. So by working for the building department, then working together with Mary Slusser and measuring monuments together with Gautama Vajra Vajracharya, I got more and more involved,” Wolfgang Korn says, “I like to explore anything that is new to me and get an answer to my curiosity. That’s how I learned and enhanced my knowledge about Newa architecture.”

About the fascinating Newa technology for building, he shares, “During the work for the Hanumandhoka project, I learned that the chukul (hinge) is the most important element in the building here because, traditionally, no metal nails or screws were used. You put a building together with beams and rafters and keep them in position with chukuls.”

“So if you start from top roofing, you pull chukuls and take rafters you can build and dismantle the structure. So, the whole thing is I didn’t know a technique that is simple but very effective before I came to Nepal.”

Kathmandu valley in his eyes

Wolfgang Korn says the Mangal Bazar area of Patan is his island of happiness today. Since 2013, he has been visiting Nepal thrice a year and staying here for up to six weeks.

He says he is in love with Nepali people and culture though he hates the traffic and the crowd. Likewise, he is tormented over how the Kathmandu valley changed with time. “For me having experienced Kathmandu as a green valley full of paddy fields, it just feels full of concrete now due to unmanaged urbanisation.”

On top of that, the 2015 earthquake that no one including him had anticipated hit the city hard and most of the historical Newa monuments got destroyed completely. He says, “I was supposed to arrive here in 2015 as well, but the trip was postponed for one month after the earthquake. After the arrival and studying the damages, it really pained me; in the beginning, while studying Newa architecture, I had never thought of an earthquake and these architectures could turn into rubble.”

Wolfgang Korn says he could not believe the change.

“Nor had I expected that the population would grow 10 times more. Between 1968 and 77, there was not one motorbike and travelling on your bicycle was normal without any problem,” he reminisces, “I used to ride my bicycle and roam around looking at the landmarks. But now, it’s all gone. There is just stupid traffic and noise. I was really shocked.”

“If it had been any normal place, I wouldn’t have come back. But my island of happiness is here.”

Nepal’s traditional architecture is now on the verge of extinction. The haphazard urbanisation, population growth and negligence of traditional technology are the reasons for its extinction, says Korn. “After the earthquake, the Newa community of the valley is being more careful. They are realising that it has to be them to work towards the conservation and preservation of traditional architecture. There won’t be any glory left if they do not care.”

He cites the example of the renovation of the Bhimsen temple in Patan where the temple’s guthi and local community contributed their skills and finances to building the same without asking for financial help from the government.

Upper Mustang project

After the Kathmandu valley, Wolfgang Korn finds peace in Upper Mustang. He designed houses for an entire village in Upper Mustang between 2014 and 2017.

“I have been to Upper Mustang for designing a modern Tibetan village. One village had to come down because there was not enough water in the field. So, they moved out to a better place, and so I went there and studied a bit of Tibetan architecture.”

To let the locals understand his design concept, Wolfgang Korn developed a technique that he worked on by creating miniature forms, using cardboard. “I realised that many people cannot read drawings. So I developed a system of creating cardboard houses so at least they can realise how it might look like.”

The new designs were also based on the traditional concept and his model also had the facility for extension of rooms and floors as per requirement.

But while being in Nepal, Wolfgang Korn is not only involved in learning and enhancing his architectural knowledge. He is actively involved in sports too.

Once, he was coaching female athletes under 14 at Mahendra Bhawan School. It was during the coaching there that he got in contact with Mary Slusser, who later published her monumental work Nepal Mandala in collaboration with Gautama Vajra Vajracarya.

Recent work

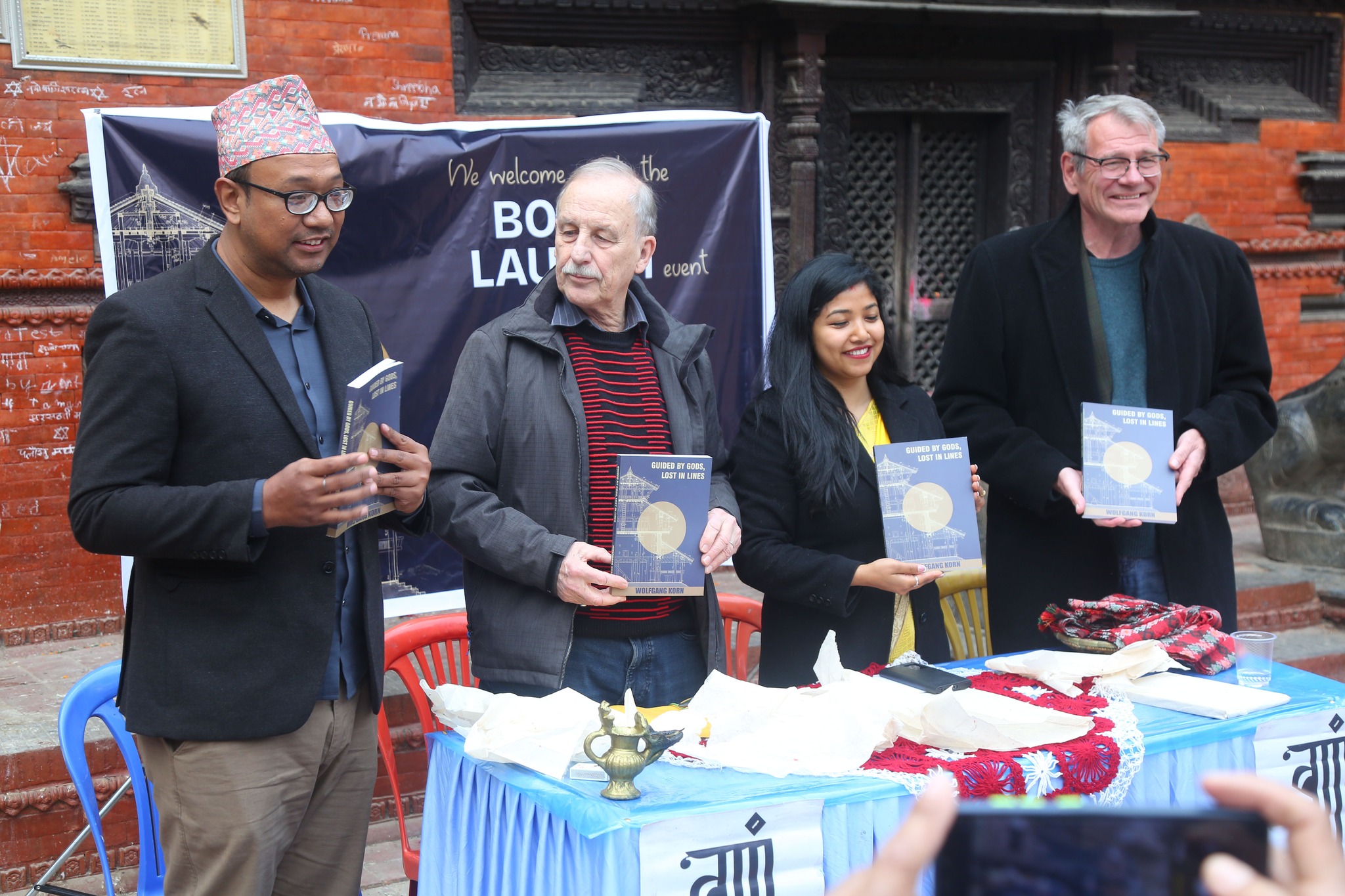

Recently, Wolfgang Korn was in Kathmandu with the support of the Senior Expert Service for his travel and the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust for his accommodation and food here. “After you are 50 years old, you do not work alone. But, to give knowledge or cooperate with Nepalis to work together, I am here.”

He visited various educational institutions sharing experiences of his work. He has already handed over most of his original drawings of Nepali architecture to the Taragaon Museum. Likewise, some of his drawings have been handed over to Kathmandu and Bhaktapur city governments.

As Wolfgang Korn looks back to the past, he finds himself being guided in a proper direction although he had never expected to be an architect. Coming from an economically weak background and parents being divorced, he somehow managed to get out of his country on his own.

“Looking back, I am happy. In my teenage, I did not have any idea about what I would do in my future,” he says hoping his experience could inspire other teens who are clueless about their careers.

,