Jiv (name changed for privacy reasons), a 25-year-old labour migrant from Nepal, had been working in Qatar for three months. But his time abroad ended abruptly when he was sent back to his home due to health issues.

Upon his return, Jiv visited a private hospital where he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. However, it is unclear what kind of counselling he received because he opted to purchase medication from a nearby Indian town and self-medicate for six months. He did not follow up with any health workers nor did he disclose his condition to anyone. Eventually, Jiv assumed he had been cured without proper investigations, and life went on.

After a few years, he started experiencing fever and cough that did not go away with antibiotics prescribed by private clinics he consulted. Around the same time, outreach workers collected his sputum sample and took it to a microscopic centre to test for tuberculosis.

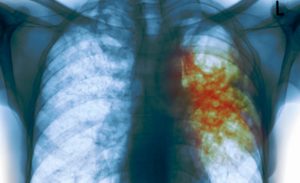

The test came back positive, but Jiv initially denied the result. After counselling, he agreed to take another test. This time, a gene-expert test was performed, which showed the drug-resistant status of his TB.

This case highlights the importance of proper diagnosis, follow-up, treatment and contact tracing for tuberculosis in Nepal. The lack of proper counselling and insufficient human resources for screening and counselling are major barriers to controlling tuberculosis in Nepal.

In this context, ownership of hospitals and local governments is essential for the proper management and mobilisation of staff and resources. These findings underscore the urgent need for policymakers to invest in TB control and prevention programmes in Nepal to ensure that cases like Jiv’s do not slip through the cracks.

Controlling tuberculosis in Nepal

After more than six decades of TB control programmes, most people now understand that tuberculosis is preventable and treatable. Still, with almost half of the population infected, the epidemiology of the disease is not about where it is, but rather where it is not. Tuberculosis in Nepal remains a major public health problem, which is still the second infectious killer worldwide and among the top 10 causes of mortality in Nepal. Since the establishment of a control centre in Nepal in 1989, there has been a systematic effort to control the disease, focusing on prevention, detection, treatment, and cure. However, there is still much to do at the community level to end tuberculosis, as there are estimated 69,000 new cases every year, with 191 new cases reported each day. The disease causes an estimated 17,000 deaths annually, with 44 deaths every day.

In Nepal, as per the annual report of 2020/21, the National Tuberculosis Programme registered 28,677 TB cases. The figure of diagnosed cases also points to the 58% of missing cases out of estimated 69,000 cases. The other alarming concern is the rising antibiotic resistance. Nepal was recently listed among the top 30 high MDR/RR-TB (multidrug/rifampicin-resistant) burden countries by the World Health Organization for 2021-2025.

Only about half of the total cases of tuberculosis in Nepal enrol themselves in the National Tuberculosis Programme, and without adequate knowledge about the presumptive cases even to health workers in rural settings, delayed diagnosis of the cases will continue. Along with coinfection of HIV among TB patients (2.4%), other chronic diseases such as diabetes, COPD and malnutrition are major factors contributing to the high prevalence of tuberculosis in Nepal. Current trends call for a substantial strengthening of efforts to reduce tuberculosis incidence to meet the goals of the WHO End TB strategy by 2035.

Weighing challenges and opportunities

The prevention of tuberculosis in Nepal has failed in primary (health education and awareness) and secondary (early detection and treatment) measures. In this context, drug compliance issues need special attention as the DOTS programme has suffered a loss of compliance with the protocol itself. However, due to the Covid pandemic, the practice of DOTS has not been directly observed as the name suggests, with the package DOTS being the norm, in which infected patients get a handful of ATT drugs for a number of days, weeks to months. There exists a poorly implemented community-based DOTS (CB-DOTS) programme too, but that has not been sufficient to monitor the anti-tubercular therapy.

In recent years, the use of telemedicine to control tuberculosis in Nepal has emerged as a proven effective method of delivering services to patients remotely. In 2014, researchers from Iowa University led by Prof Keith Mueller demonstrated the use of tele-emergency services providing immediate and synchronous audio/video connections, between rural low-volume hospitals and an urban “hub” emergency department. The Curative Service Division has been planning a similar model of telemedicine services in Nepal.

Similarly, in 2018, Richard S Garfein and his team from the University of California San Diego generated evidence to demonstrate the multifold benefits of using video technologies (video-DOT) in monitoring tuberculosis patients. Another study comparing smartphone-enabled video-observed versus directly observed treatment for tuberculosis shows VDOT is likely preferable to DOT for many patients across a broad range of settings, providing a more acceptable, effective, and cheaper option for supervision of daily and multiple daily doses than DOT.

Several such new innovations can be used in controlling tuberculosis in Nepal.

Acting local

In Nepal, a five-year action plan for 2021-2026 has been implemented, aligning with a pledge to end tuberculosis in Nepal by 2035 and eliminate it by 2050. However, there is a need to scale up the necessary infrastructure and human resources and increase access to diagnostic tools, tests, and drugs.

Meanwhile, to create role models at the local level, the government has launched the TB-free municipality programme in 22 local units to achieve tuberculosis-free status within five years. However, the effectiveness of health programmes depends not only on the availability of resources and infrastructure but also on cultural, organisational and political factors such as festivals, elections, human resource turnover and unstable governance that cause occasional disruption in the otherwise regular programme.

Amidst all these, there have been debates about whether federalism has impacted the health sector and public health interventions in an unexpectedly negative way. However, there is no clear evidence to support or refute this narrative. Regarding tuberculosis in Nepal, under federalism, local leaders have shown a willingness to support public health interventions and manage cases. Local governments are now more involved and take responsibility for prioritising and funding various programmes. Additionally, local governments can facilitate more effective diagnosis and treatment. However, while commitment is abundant, accountability can be lacking.

Tuberculosis in Nepal is a litmus test of our social progress. A social disease such as tuberculosis and the economy are interrelated and demands social security in tuberculosis control plans and implementation. In Pained – Uncomfortable Conversation about Public Health (2020), Sandra Galea and Micheal D Stein present a beautiful metaphor of football, which says regardless of the competence of the goalkeeper (medicine), if the other ten players (social determinants) are not playing well, the game cannot be won.

We know how tuberculosis is transmitted, and how it can be stopped, and treated; we have tests and drugs provided free of cost to the people. Yet we are failing to control tuberculosis in Nepal. This should be acceptable, neither as a health worker nor as a citizen.