Before he migrated to Kathmandu at the age of 10 in 2001, Saaune Sankranti used to be one of the most interesting festivals of the year for Dinesh Sharma, a native of Kavre. Since then, every year on the first day of Saaun/Shrawan, the fourth month of the Nepali calendar, he just misses the day—for he cannot celebrate it in the way he used to do. In particular, he misses the Luto Phalne tradition.

“The biggest fun was in the evening,” Sharma, now 30, narrates, “The whole family would gather in the yard, outside the house, ignite small pieces of firewood and throw them on all sides—wishing we would not catch luto (scabies) throughout the year.”

After migrating to Kathmandu, Sharma found such a tradition was not present in Kathmandu. However, he is also aware that the tradition of throwing away lighted fire wishing good health is not as vibrant as it used to be in his own village also. As the young people of the village are in cities or abroad, the tradition is dying out gradually.

Though the Luto Phalne festival sounds strange for the new generation of Nepalis, the festival used to hold a significant position in the lives of rural Nepalis, culture experts observe, highlighting reasons for the celebration.

When?

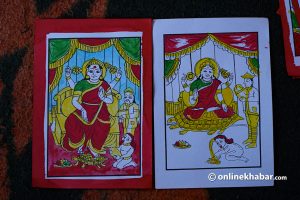

In the evening of the Saaune Sankranti, people celebrate Luto Phalne festival by worshipping the night god Kandarak.

Cultural expert Jagaman Gurung says the festival is directly linked to the agricultural tradition of Nepali society. “Whereas the farmers get busy throughout Ashadh planting rice, the festival marks the end of the hectic schedule.”

“While planting rice in the field, farmers work barefoot in muddy water for long hours. They have to get wet in the rain during plantation,” Gurung explains the logic behind the festival, “Such farming activities could invite various skin diseases like scabies to their bodies. To ward off such problems and the itchiness it causes, this day is celebrated as a cleansing day of the whole body.”

From the religious perspective, Saaune Sankranti is an important day, hence it is a good time for celebration, according to Nawaraj Ghimire, who teaches Puranas at Valmeeki Vidyapeeth.

How?

As explained by Gurung, to observe the Luto Phalne tradition so as to take away scabies traditionally, first, a part of the front yard of the house is smeared with either cow or ox dung. Then, two balls of cow dung are made and on them, cucumber flowers are kept. Also, in the smeared part, a taro leaf (karkaloko paat) is kept and over it, green chilli, peach, dropping fig (khanayo) and corn are placed.

After that, two bundles of small and thin bamboo stems are taken to the oven in the kitchen to ignite the fire. From the kitchen, it is brought back and placed beside the two cow dung balls. Then, herbs like mugwort (titepati) mixed with ghee are burnt there.

According to Gurung, it is believed that the area from where the burning torch is thrown away up to where it lands comes under one kingdom, traditionally the kingdom of Sinjatpati. Sinja, currently a part of the Jumla district in Karnali, apparently, is the place where the Nepali language and Khas culture originated.

Again, four torches from the kitchen stove are brought outside and thrown on all four directions, chanting “Luto Laija…Luto Laija” (Please take away scabies). Meanwhile, everyone plays drums and bells or even bangs plates and other kitchen utensils to make noise.

Finally, a bundle of locally available herbs such as asparagus is kept under the roof of the house to conclude the Luto Phalne festival.

Why?

Gurung stresses the Luto Phalne tradition includes all aspects of human life including psychological, religious, scientific, and cultural ones. This tradition also gives the exhausted farmers time to rest and indulge in the rituals.

Adding to this, historian Dinesh Raj Panta points out that this tradition in all ways connects nature and the god to human life. “As this tradition is related to the cleansing of the skin diseases like scabies and allergies, it signifies the importance of health in human life,” he says.

Gurung points out that, scientifically also, viruses are killed or cleansed by heat or fire. During this festival as well, the viruses of the land surface are destroyed by the burning bamboo stems’ bundle and the viruses on the air are destroyed by the torches thrown in all four directions.

Also, the firing of bullets and noise from bells, plates, and drums during this festival act as a sound therapy for many, he claims.

Therefore, other communities except for the Khas people also have similar rituals and festivals in their annual calendar though they do not observe this Luto Phalne tradition, according to Gurung. For example, the Newars of Kathmandu celebrate Gathemangal.

Strangeness in Kathmandu

Despite being originated in western Nepal, the tradition is in existence in eastern Nepal also. However, it is completely a strange affair in Kathmandu. Why?

Gurung surmises it is because there were a few Khas people—Brahmins and Chhetris—in Kathmandu in the past, and they did not have the capacity to establish this tradition. “Newars live in the centre of the valley and ethnic groups such as Gurungs and Tamangs inhabit the edges of it. The Khas people live in between, the area called Kaanth,” Gurung explains, adding perhaps the Khas people felt sandwiched between different ethnic groups from both sides and gave up the tradition.

Originally published on July 16, 2020.