For more than seven decades, human trafficking has been a major issue for Nepal, with people being coerced or deceived and traded domestically and cross-border. The National Human Rights Commission’s annual trafficking in persons report for the fiscal year 2018/2019 has stated that 175 cases of human trafficking have been registered in Nepal, but it promptly assumes that way more cases might not have been reported yet. The stakeholders say the underreporting is backed by a number of factors; the chief being people’s conventional perception that only the ‘sale’ of women abroad for the purpose of prostitution amounts to trafficking.

Sarah Rich-Zendel, a post-doctoral research fellow at York University, has been studying the scenario in Nepal for the past few years. As a senior research manager for the Human Trafficking Vulnerability Survey, a joint project of the University of California, Berkeley and York University, she has been looking into the impacts of awareness-raising anti-trafficking campaigns in Nepal. Coinciding with International Women’s Day, Onlinekhabar recently talked with Rich-Zendel about her research findings, the state of human trafficking in Nepal and other related issues.

Can you please tell us about your research project?

We started the project in 2013 with the intention of testing how effective anti-trafficking campaigns are. There are lots of international and local organisations which have been investing a lot of money and resources into such campaigns all over the country. But there’s very little evidence of what kind of effect they have on people’s attitudes towards trafficking; their beliefs about what trafficking is; and what the nature of the problem is. So the purpose of our study is to design campaigns that were locally relevant and very high quality and disseminate them and test them. We would survey people before and after experiencing the campaign or being exposed to it and then we would see how it affected what they thought about trafficking.

So what did you find?

We got some very interesting findings because the study was very large. We had a sample size of 5,000 participants from 10 districts in Nepal that covered a range of geographical locations, caste and ethnic group, and age group. And, we tested a lot of different types of campaigns.

Some of the campaigns are very scary and they try to use fear to raise awareness. Others might be more empowerment-based. Some have been on the radio. Sometimes you see a poster campaign. So we wanted to test all of these possible variations. And what we found was actually that empowerment narratives–when you use a campaign to tell a story and that story to empower someone and to raise awareness through empowerment–are much more effective than the campaigns that you use fear and try to use very scary images or focus on more of the danger aspects of trafficking. For example, the empowering campaigns have made people able to retain knowledge and facts about trafficking and dispel misconceptions about trafficking.

Why are many of these campaigns focused on cross-border trafficking?

One of the largest misconceptions about trafficking (in Nepal) is that it’s only cross-border. But actually, in Nepal and in many places around the world, domestic trafficking is a very big problem and often people are not aware of that because so many campaigns focus on cross-border trafficking. That means people are going to be less vigilant and careful around a practice that may make them more vulnerable to domestic trafficking. They’re less aware that it is a common problem. So, our research wasn’t focused on trying to determine what the prevalence of trafficking is, but we were focused mostly on the kinds of ways that campaigns can be used and how effective they are at dispelling this myth that most trafficking is cross-border.

Yes, then, please tell us more about how effective they are.

We found that the campaigns are actually quite good if you design them in a certain way that they can correct that kind of misconception that it’s only cross-border. So the campaigns that we designed, for example, told stories about domestic trafficking and gave information about the real dynamics of domestic trafficking in Nepal or the ways that they can occur in terms of child labour, for example, in a brick kiln. Another is the entertainment industry in Kathmandu. There are lots of women who travel to Kathmandu looking for work and end up potentially being coerced into doing work in the entertainment industry. So there are all sorts of domestic trafficking in Nepal. And, I think people are less aware of them than the typical story of cross-border trafficking into India or elsewhere.

I think a lot of campaigns that you see present very simplistic, and often sensational, examples about what trafficking looks like. But the reality is it can happen in many ways and often there’s not just one dalal or agent that’s the trafficker, but there are many ways throughout. For example, migration choice that someone makes where they can become exploited: they may engage with an employment agency; they may take out a huge loan to be able to travel abroad and once they get to their job and the destination country, their contract may be changed. And they may find out they’re getting paid a lot less. All of these types of dynamics make the story of trafficking less simplistic than with one agent. It can often be a lot more complex of the story than that. And I think people are less aware of the risks of being trafficked because in their minds they make most of it as a very simplistic notion of what trafficking is and how it occurs.

So how can the campaigns be more effective when the vulnerable populations are living in poverty?

I think we have to understand that awareness-raising is just one small tool in a much larger toolbox. A lot of people migrate for work and they migrate because of economic issues and poverty or lack of employment. A campaign cannot solve that. So it’s limited in what it can do in terms of reducing vulnerability and it can only be a part of larger social changes that would need to reduce the vulnerability in the social dynamics.

So how are patriarchy and human trafficking linked in the case of Nepal?

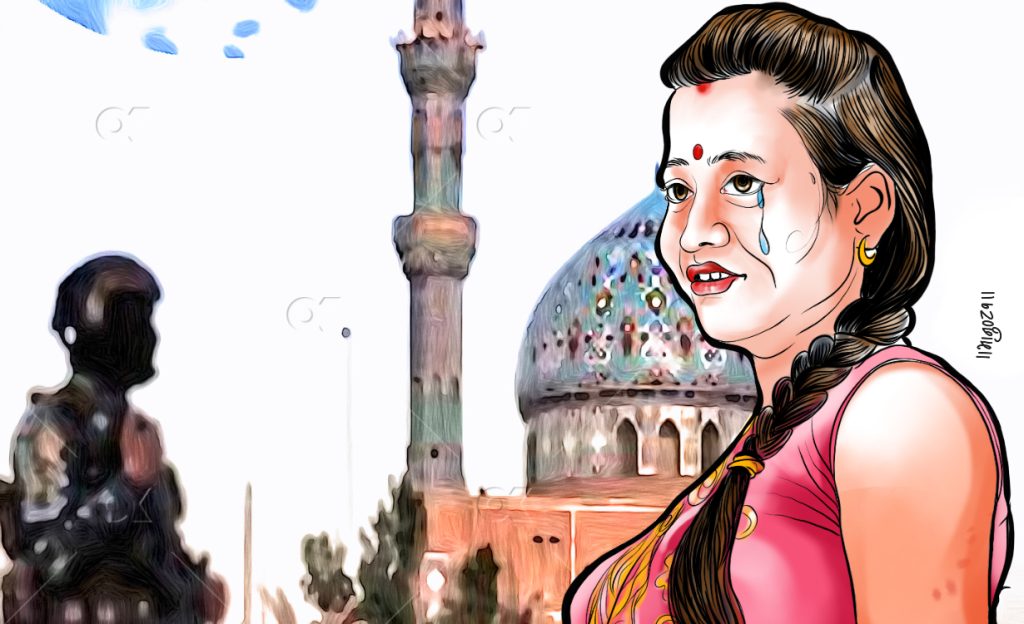

A lot of people conflate human trafficking with sex trafficking and they think of all victims of human trafficking as women. And a lot of campaigns represent women as someone lacking agency or being very dependent and needing to be rescued and protected. That can actually reinforce a lot of patriarchal ideas about women and their agency in the choices they make when it comes to employment. So I think it’s very important to think about gender when you’re designing a campaign on the one side because it’s important that the campaigns present empowering images of women.

And, it is really important for people to understand that men are also very vulnerable to trafficking as well through labour trafficking and even sexual exploitation through the trafficking pipeline. But I do think that there is a risk that the campaigns might reinforce their patriarchal ideas of those women. And there’s a lot of feminist literature about the way that anti-trafficking advocacy can increase the stigma of sex work, sex work that’s done by choice.

So from your research in Nepal, what is the status of women empowerment, overall?

I have been living and doing research in Nepal for almost 15 years. I’ve had the opportunity to do a lot of research here. I’ve done research on discrimination against women in the Nepali prison system. I’ve done research on fair trade and the effects of fair trade on women’s empowerment, and on the implementation of sexual rights reform. One of the insights that I’ve had is that there is a lot of really amazing work being done here to address gender inequality, to address the patriarchy.

Here are the things that people, women’s rights activists and sexual rights activists all over the world can learn from. But I also think there’s a lot of the influence of ‘international development thinking’ about gender that sometimes the voices of more radical activists get lost in them. I think the international development industry has its own sort of interest in terms of implementing programmes in a certain way and that can often make less visible what local activists are doing.

For example, in my fair trade study, I looked at Palpali Dhaka weaving, which is a type of weaving so unique to Nepal. There’s a lot of opportunity in that industry to promote an art form that you know at its core is very Nepali. But then when you have the fair trade industry come in and want to bring in certification and designs from the outside, I actually found that women who were weaving for the fair trade industry were a lot less satisfied with their work and they felt it took a lot of pride in their work. So when we think of fair trade as necessary for empowering for women, the women I interviewed who worked in the Palpali Dhaka industry were extremely empowered before any of these. They were proud of their work. They were excited about what they were doing. They had a lot more control over their work environment and organising. So I think we just take for granted that a lot of new programmes are relevant and are going to be effective when actually that may not be the case in certain contexts.