High craggy hills always fascinate me. I often gave a longing look at the Shivapuri hills, always in my sights from my house at Dhapasi, and thought about riding my mountain bike to those wooded heights located north of the Kathmandu Valley.

The big day came, and Khasing, my co-rider, and I set off to do the Nagi Gompa-Sundarijal track deep into the Shivapuri hills.

We completed the first leg of our ride at Budanilkantha, a Hindu shrine famed for the 5th-century image of Vishnu (who reclines over water, resting on a bed of coils formed by the thousand-headed snake-god, Shesh nag). The Shivapuri hills towered above us as we headed north on a sharp incline—enough to scare first-timers. Darn! the incredibly steep road never seemed to end!

We kept on stoically in between brief rests.

I sighed with relief when I spotted the Shivapuri-Nagarjun National Park gate at Muhan Pokhari. The dirt track inside the park appeared still moist with early morning dew. The forest was so thick that the sun hardly penetrated through the dense canopy as we pedalled uphill under the dappled light.

The ride was quiet save for creaks of our saddles, shifting of gears, scraping of spinning wheels, and our own breathing. Not a soul was in sight. Only the intermittent calls of birds greeted us.

The forest was so thick that the sun hardly penetrated through the dense canopy as we pedalled uphill under the dappled light.

The lush Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forest included pines, alders, wild Himalayan cherry, oak and rhododendron. My eyes kept straying, hoping to spot wild animals—barking deer, a flock of foraging Kalij pheasants, or an intimidating wild boar rambling idly through the forest. The Shivapuri forest is home to leopards, too, but I did not relish the prospect of seeing one of those crossing our path.

Suddenly, a crashing sound in the heavy cover startled me and I jumped on my saddle. Fearing the worst, I looked hard but soon spotted the culprits, harmless primates: rhesus monkeys.

After an hour’s uphill climb we stopped at a small clearing to catch our breath. We took in the sights. The wooded hill descended to the valley’s floor. A beautiful countryside sprawled out from the foothills. But it didn’t get far. All we could make out in the distance was

A beautiful countryside sprawled out from the foothills. But it didn’t get far. All we could make out in the distance was a mass of tiny concrete forms swathed in an impenetrable haze thickened by pollutants. The city, the distance, the future looked bleak.

Another hour brought us to a fork in the track; Nagi Gompa (a Buddhist monastery) lay uphill to our left. After a brief respite, a sip or two from our water bottles, we continued our climb.

That was the most grueling incline we had done so far. Khasing seemed to take it in his stride, but I tired soon and had to dismount. I rested a while, walked the bike a little and then somehow managed to huff and puff it to the gompa.

Built onto the hillside gradient in a split-level fashion, the monastery consists of two main temples and number of outbuildings. Painted gold and ochre, the gompas house large statues of Buddha, revered rinpoches (religious teachers revered in Tibetan Buddhism) and illustrious Karmapas (heads of the Karma Kagyu sect), while intricate Tibetan patterns, artifacts, and scroll paintings adorned the walls in splashes of vivid colors.

Set up exclusively for anis (Buddhist nuns), the nunnery housed dormitories, classrooms, and meditation chambers.

Khasing and I stopped to rest at the foreground of the lower gompa. Prayer flags festooned the monastery perimeter. They whistled in the wind, a riot of colors against the calm and idyllic surroundings. Shortly, a head-shorn plump old lady monk, dressed up in her saffron robe, approached us and uttered some words, which at first sounded like complete gibberish. As we looked at her helplessly, she repeated herself. We finally understood.

We finally understood.

As it turned out, the nun was suffering from a local malady called janai khatira, a kind of skin allergy that develops into a burning rash and mild swelling. The only known remedy for this ailment is to draw a picture of a simha (lion) on the affected part, a common practice all over Nepal. Unfortunately for the ailing lady, the nunnery had no one deft at that, so she turned to us for help.

Unfortunately for the ailing lady, the nunnery had no one deft at that, so she turned to us for help.

Frankly, I wanted no part in it; the whole idea sounded embarrassing. When a nun fetched a pen, I quickly turned her toward Khasing.

As Khasing reluctantly went to work on the bared back of the lady, I watched in silence. The allergy looked bad.

Then the ‘pick-axe’ fell! The lady suddenly turned around, mumbling something, and bared her chest. Time seemed to freeze and so did I.

But Phasing hardly noticed! He proceeded with the drawing, the pen steady in his hand. Out of common courtesy, I looked elsewhere. After what seemed like an eternity, the ordeal was finally over.

Still reeling from the unexpected drama, we took a tour of the gompa. We watched as the anis, old and young, went solemnly about their ways.

Amidst the profound ambiance, we also observed very young nuns scampering around excitedly, giggling and whispering to each other. We also conversed briefly with some of the nuns.

Some even greeted us in Tibetan, “Tashi delek.”

We learned that Nagi Gompa (TsunGon Nang-kyi Tongsal Ling in Tibetan) housed over one hundred nuns, from 12-year-olds to 80-year-olds.

After half an hour, we continued on our way.

As we descended down to the lower gompa, drums and lavas (long-stemmed Tibetan horns) sounded from the upper gompa and the revered mantra, Om Mani Padme Hum wafted resonantly through the air, making us solemn with reverence.

But the old nun insisted on offering us tea and we had to oblige. A brief conversation followed, and we learned that the 79-year-old ‘lady’ had lived in the monastery for almost 45 years.

“What’s your name?” I asked as we sipped tea, completely unaware that the dreaded ‘pick-axe’ was about to fall for the second time.

“Maila Lama,” she replied. Did I hear it right? I wondered.

“It’s Mailee Lama, right?” I tried to correct her.

“No, no, it’s Maila and not Mailee,” she reiterated.

How on earth could a woman have a man’s name, I wondered. “But you’re a woman, right? So it should be Mailee, no?” I stood my ground.

“No, no,” she flourished a toothless grin, clearly amused. “I’m not a woman, I’m a man. Since the gompa needed a male lama to look after the daily affairs, the management decided to consign me here.” An awkward silence settled in.

All Khasing and I did was gape at each other stupidly, in disbelief. And all the time we believed that he was a she!

“Unwind, got to unwind,” my mind screamed at me.

Khasing seemed no less pent-up.

Then, in the middle of the jungle where we stopped to eat our packed lunch, we bent double, slapped our thighs and shrieked with laughter, certainly scaring the most fearless leopard if one happened to be lurking in the nearby bushes.

The rest of the ride to Sundarijal through dense growth on a steep downhill packed an adrenaline flowing experience, the suspensions on our hardtail bikes doing extra work as we tore down the gravelly track.

Khasing and I parted our ways at the Narayan Gopal Chowk, and as I pedalled home, the weird, rather hilarious incident at the Gompa kept coming back to my mind. I chuckled to myself. We’d had a truly memorable day indeed, I thought.

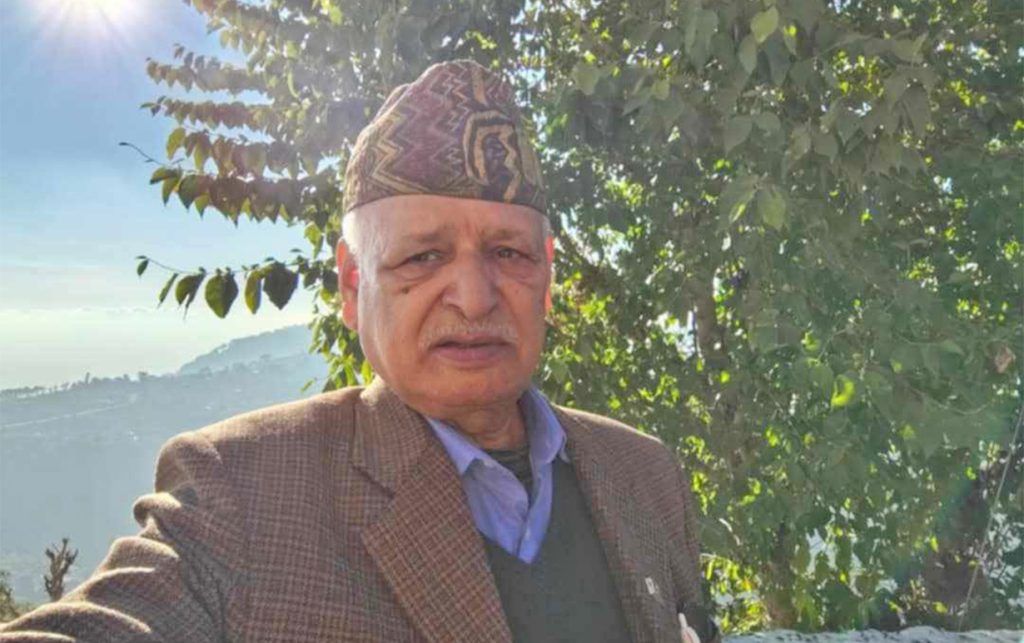

Opening image only for representational purpose.