During the decade-long conflict between the Maoists and the Nepali state, the country witnessed bloodshed, unprecedented in its recent history. As the war raged on, it was not only the Maoists or the state’s security personnel, who paid the ultimate price, thousands of unarmed people also lost their lives.

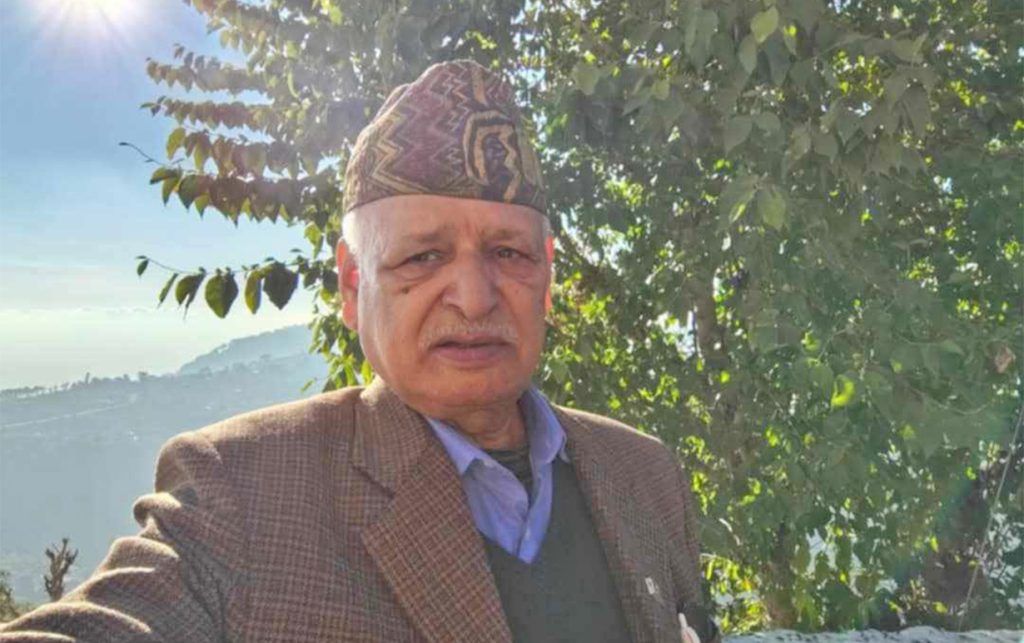

Rabindra Shrestha, an artist based in Kathmandu, was observing the events closely. Even after the peace process began in 2008, peace still looked elusive, especially as the dispute over the integration of Maoist fighters into the Nepali Army escalated.

During that period, Shrestha was working as lab assistant at Sushma Koirala Memorial Hospital, named after the wife of then Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala. Shrestha, a traditional artist adept at making ‘thankas’, was not fond of his job as he had to take it up out of compulsion. An economic crisis at home had him train as a lab assistant at CTEVT, Nepal’s technical school, and get placed at the hospital.

Little did he know that the artist in him would find ways to make his job a bit more ‘interesting’. During his nine-to-five workday, Shrestha had to deal with blood, that too the ‘blood’ of war.

There were times when Maoist combatants, wounded in the war, would come for treatment, and times when soldiers and policemen wanted to see the doctor. “They would narrate horrific tales of the conflict, and that would send shivers down my spine,” Shrestha remembers.

Within a few weeks, Shrestha could see nothing but red. Bright yellow, white, purple, everything was red for the artist, who had until then only made forms of gods and goddesses with the strokes of his brush.

“Why paint gods and goddess at a time of such bloodshed?” he had asked himself. There was no point doing it.

“If everything appears red, then why not paint in red?” his thoughts began to wander. “If I am painting in red, why don’t I use the deepest red?”

The deepest red, for him, was human blood. With consent from his friends, some of whom were Maoist fighters and soldiers, Shrestha started painting in human blood.

“So many people died in the war, thousands got orphaned, widowed or disabled,” the 38-year-old shares. “I did not find a medium better than human blood to portray what was going on.”

Shrestha painted a series of 10-15 artworks human blood. But one of them holds a special place in his heart. He gave it the title ‘The Integration’.

For the painting, he took some blood from a Maoist fighter, and that from a soldier. Using the mix, he painted an ‘eye’ of peace near the centre of his canvas. For the background, he filled the rest of the space with his own blood.

“Looking at the painting, you won’t be able to say which part of it I painted with blood from a combatant, and which part of it from a soldier,” says Shrestha. “That is true integration.”

He says, “No matter how hard we fight one another, in the end, there is no option but to reconcile.”

Shrestha’s painting has been featured in different exhibitions across the country. Leaders like Mohan Baidhya and Krishna Bahadur Mahara, who played important roles during the conflict, have all seen it.

It was only a few years ago when Shrestha realised that his work could be interpreted as being against human rights. “But it was time that demanded it from me.”

“Nowadays, I don’t dare think of painting with blood.”

Shrestha, who is now a student of fine arts at Kathmandu University, has drawn a line under his past, that too literally. For his six-month-long project, he has chosen ‘Line Art’ as his area of interest. During the course of his work, he recently collaborated with 20 artists, including some big names such as Sashi Shah, Kiran Manandhar, Manuj Babu Mishra and Birendra Pratap Singh, to put together ‘The Line: Soul of Universe” series.

For the series, he gave each artist a 6X3 ft canvas on which he had drawn 3″ lines. The artists then had to finish their work within the lines he had drawn. The artists, while staying within Shrestha’s lines, painted things abstract to concrete, and in a myriad of styles.

Shrestha’s transformation into a ‘line’ artist began six year ago when his teacher at KU commented about the lines and shapes in his work. “Sometimes he would say a line was not just right, and he would erase it. There were also times when he would draw a circle around some line,” he remembers.

That inspired him to take ‘lines’ as his area of interest.

Soon he realised that universe itself is just lines. “Look at the line (queue) people stand in to go to Korea, look at the lines that connect different parts of the world now.”

A line starts from a point, and ends in a point, most people believe. But for him, the story is a bit different. “If you zoom into a point, you see a circle, and that is also made of lines.”

But at the end, regardless of the medium, blood or lines, the message he wants to convey remains the same. “We are all different, but we are interconnected, and we are the same in many ways.”

From the archive: http://english.onlinekhabar.com/2016/08/23/384497