Fishing has always been an abiding passion for me. So, I jumped at the idea of a fishing trip (some seven years back) to Roshi Khola (river) when my teammates planned it. It was, however, a different kind of fishing–electro-fishing to be more exact. And it was more a mission than a fun trip.

Electro-fishing is a scientific process of stunning fish by using electric current powered by a portable backpack generator or battery. The current is delivered by a pair of electrodes that comes with the equipment. Exclusively used for scientific surveys, fishery biologists use it as the most humane way of catching fish, before releasing them back into the wild.

Our purpose too was a scientific survey aimed at determining the fish abundance, density and species composition of the Roshi River. We had to catch fish to carry out our mission. Electro-fishing, when done properly, results in no permanent harm to fish.

Sadly, to the detriment of our aquatic life, for the past decade, people invented crude replicas of this equipment for the indiscriminate and unethical killing of fish on a mass scale for eating and selling, which has reached epidemic proportions the length and breadth of our country.

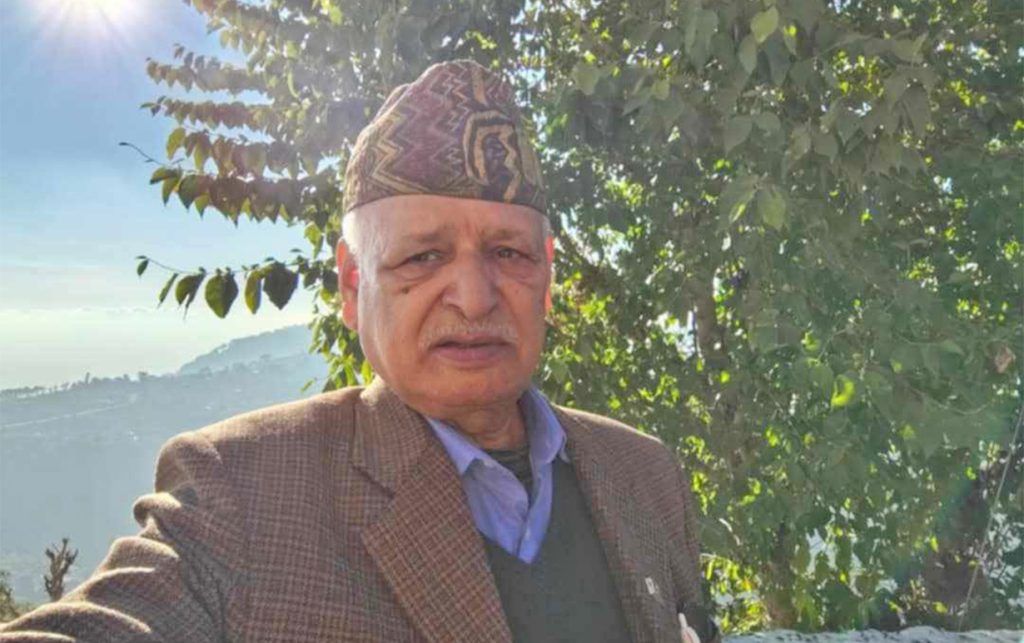

We were five in all, Arun, Vikas, Kumar, and I. Professor Bibhuti Ranjan Jha was a guest and our mentor. Everybody addressed him as Jha Sir, so he was ‘Jha Sir’ to all. A senior environment scientist at Kathmandu University, Dhulikhel, he had volunteered to join us as our ‘guru’. The equipment and all the paraphernalia for the survey were provided courtesy of Jha Sir.

It was almost noon when we arrived at the Roshi Bridge via the Banepa-Sindhuli Highway. As we sped along the new highway (paved only up to Nepalthok then), all eyes turned to the clear Roshi after it appeared as we crossed a bridge over it. The Roshi tumbled past rocks and boulders strewn all along the watercourse as it snaked through the narrow valley.

The river Roshi is named after a tiny village (Roshi Gaon) located on a hillside some three kilometres from the old historical Newar town of Panauti, seven kilometres south-east of Banepa.

Noted once for delectable asla (snow trout), the spring-fed river drains from the high Phulchoki hills (above Godavari), and converges on the Sun Koshi river at a small settlement called Dumja (on the Sindhuli-Bardibas highway), some 55 km from Dhulikhel.

The Roshi today, however, stands depleted and degraded. Over-fishing (electro-fishing included), burgeoning settlement, development works (during the highway construction), and massive excavation of sand, gravel, and boulders has violated the once pristine river.

Except for Professor Jha, all four of us (avid anglers) represented an NGO involved in the conservation of aquatic resources of our country.

As we drove down the highway surveying the river that flanked the road, we passed by a stone-crushing site by the riverside. The gin-clear Roshi after that point turned disbelievingly turbid and continued that way—getting worse as a few kilometres down another plant spewed silted water into it.

At a place called Dumja, the lesser Roshi finally merged with the robust Sun Koshi River at Dumja. It was shocking to watch the dark chocolate Roshi in stark contrast to the turquoise water of Sun Koshi as it tumbled into the big river.

Our survey began at the Roshi a little farther up Nepalthok where the water was clear and unsoiled by the stone crushing factories. The balmy day with the sun not too strong promised an agreeable weather. Without further ado, our team pitched into work. Care had to be taken as the riverbed was uneven with slippery gravel and stones.

Off went the foursome (Kumar, Arun, Vikas and Jha sir) into the Roshi, knee-deep (waist-deep some places), struggling against the current upstream. Kumar, weighed down by a bulky generator on his back, clumsily waded through the water holding the ominous looking stick with the electrodes, which he kept poking into the water while his other hand fiddled with a switch that delivered an electric current.

Arun and Vikash in unwieldy waders flanked Kumar, holding long staffs attached to dip nets. The work began and the duo started jabbing the staffs left and right to trap the stunned fish. Prof Jha brought up the rear with a plastic bucket that held the fish netted by Arun and Vikash. All were wearing chest long mandatory rubber waders (with boots attached) to avoid the risk of getting electrocuted.

I elected myself to be the team-photographer and no less excited than my colleagues, clicked furiously on my Canon G-9 from the banks. At first sight, it looked like total bedlam, a bunch of weirdly outfitted guys working the river with long staffs in frenzy.

“Hey, try that eddy…no, no not that one, the one on your right,” an over-excited Arun bellowed at Kumar. “Shove the stick deeper. Try to reach underneath the big boulders”. Everyone had to yell over the sound of the rushing water. Now it was Vikash’s turn to shout: “There, there . . . Arun, the fish are to your left.”

Professor Jha apart, the young men (in their early thirties then) launched themselves into a raucous bubbling energy, worth watching. Excitement mounted with the passing of every minute.

Words flew. The yelling took newer heights. As expected, the entire scene of frenetic activity coupled with the noise successfully drew a small local crowd, who watched in awed silence.

Suddenly, when only five minutes remained to complete the first leg of the operation (15 to 20 minutes to be done at 2 different stretches), the generator coughed, sputtered, belched out black smoke, and died to everybody’s, “Oh, no!”

Despite several attempts, the gen-set refused to budge. All four reluctantly waded out the river. And then, Vikash stumbled, lost his footing, and crashed into the water followed by a burst of guffawing from the gathered local crowd.

As it turned out, the gen-set had its spark plug fouled. A quick scrubbing of the plug did the work, though and the gen-set kick-started to everybody’s . . . “Hurray”! Since that particular stretch was already disturbed, we worked up from a different spot downriver.

It was time for a lunch break. We helped ourselves to hefty tuna sandwiches–by courtesy of Arun. After a lip-smacking lunch and a bottle of chilled Coke, we all got down to the final work. An excited Kumar checked on the day’s catch stowed in two different buckets.

As it appeared, the last combing operation had yielded more fish, finger size and smaller. Every fish had to be taxonomically categorised by its native identification, scientific name, weight and length. The total count of each species assessed its abundance in the river.

I took a little time off to satisfy some of the local fellows’ curiosities. A local fisherman with a cast-net slung over his shoulder seemed the most inquisitive. After I explained to him about our survey, I asked him: “So, how is your fishing going on?”

“Very little, sir; it’s not like what it used to be. Ten years ago, my cast-net brought enough fish to support my family. There are no fish in Roshi, today. I fish these days in my spare time only, doing odd jobs to earn my bread,” lamented Krishna, the local fisherman.

Of the eight different species captured, totaling 214, Bhote Gadelo, a loach (Schistura Rupecula), had the highest abundance (106 total count); next were, Katle, copper mahseer (Neolissocheilus hexagonolopis):53, and Buche Aasla, Blunt–nosed Snow trout, (Shizothorax richardsonii):12, to name a few.

None of the catch, disappointingly, included the Golden Mahseer, tor putitora, (the most-coveted fish by the anglers) although the spring-fed Roshi offered adequate rocks, pebbles and gravel beds—a perfect spawning ground for this species from the Sunkoshi River. “Darn it!” snorted Vikash to show his frustration.

It was time for the fish to be released. Arun volunteered and grinned from ear to ear at the camera. The locals watched in awe; bewildered (although we had explained) at the entire catch being released.

Darkness approached while we packed up for the day. We shook hands with Krishna and the local bunch, who kept us company to the last bit, and piled into Arun’s battered old jeep (almost 30 years old!) that screeched and groaned with faults in every conceivable part.

A little later, as we crossed the Roshi Bridge, I looked back at the river to find in the fading light a streak of silver that wound its path across the darkening valley, as gentler hills stood out on two sides in somber silhouettes. We really had a fantastic day of fishing . . . and for a good cause, I mused.