Suman Gaudel of Naradevi, Kathmandu, shut his four-year-old grocery named Suman Cold Store in April after the second wave of Covid-19 started in Nepal. He then returned to his ancestral home in Tanahun just a day before the lockdown (prohibitory order) began in the Kathmandu valley.

Gaudel expresses, “I was already in debt due to the first wave of the pandemic and resultant lockdown. And, this time, I had to shut my shop forever and return home and do farming due to the fear of increasing debt”

He is just one representative. According to the Nepal Retailers Association, the number of people leaving retail businesses during the pandemic is around 1,800.

Struggle of scores

Gaudel further explains, “During the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, I could not even pay the rent from the overall business. I even had a hard time managing sufficient meals for my family. Therefore, I ended up taking out a loan.”

Even in the ‘normal times’, when Gaudel used to run his shop for around 15 hours a day, he used to hardly manage all his and his family’s expenses. “I had to pay Rs 15,000 a month in rent for the shop and Rs 7,000 for my flat. However, I could not even make Rs 20,000 monthly from the shop. Therefore, I was forced to leave Kathmandu. Once everything gets normal, I will look for a job but will never return to the grocery business again.”

Ganga Sigdel of Kirtipur also has a similar story. She also quit the business as she could not make a living from her shop. Making their condition worse, her husband, who has been living abroad for four months, was also not paid by his employers. On the advice of her family, she returned to her home in Rasuwa during the prohibitory order with all her belongings and even enrolled her daughter in a school there itself.

Similarly, Deepak Rupakheti (name changed), who runs a retail grocery shop in Naya Baneshwar, shut his store last September. He was booked by the Department of Commerce during market monitoring for selling sugar at a higher price (Rs 4 more than the set price for a kilogram).

“I had to pay a hefty fine for the mistake made in the wholesaler’s bill, and my year-round earnings went in one fell swoop.” This was not the only reason for Rupakheti to shut his shop; he further complains that his sales were hampered due to the opening of a new supermarket nearby.

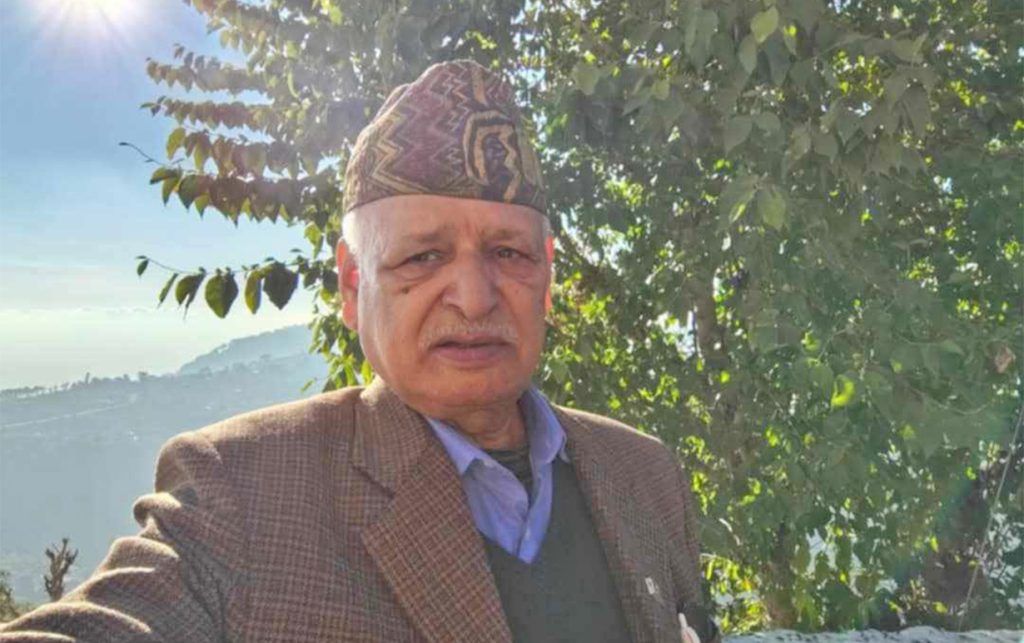

As per Dhruva Adhikari, a central executive member of the Nepal Retailers Association, hudnreds of people who used to run retail groceries including food and vegetable shops have left the business.

“After the first lockdown, the number of our members has dropped from 4,000 to 2,200.”

The association’s general secretary Amul Kaji Tuladhar also reports retailers have been displaced due to the slowdown in business. He further adds that retailers became the victims of the pandemic, government policy and a decline in consumer spending.

Why were retailers displaced?

According to Tuladhar, the government adopted different policies in the operation of supermarkets and small groceries during the first lockdown in 2020, thus supermarkets and department stores earned well and retail shops went onto the verge of shutdown.

“Even during the lockdown, the government took a discriminatory policy against us. There was a lot of competition when the grocery store was given a fixed time to open,” states Tuladhar.

According to Adhikari, consumer spending has fallen as the source of income has shrunk due to the pandemic, therefore, sales or transactions have been reduced by up to 20 per cent. This is also because many people have left Kathmandu to their permanent addresses.

He further adds that some of the shops were closed forever as there was no sufficient sale, and they could not transport new items from the wholesalers.

“Even in market monitoring, there is also discrimination between supermarkets and retailers,” adds Adhikari.

What kind of businesses were displaced?

According to the association, retailers with small investment and shops where consumers from far and wide usually come to shop have been affected more by the prohibitory orders and lockdowns. “Similarly, a lot of information has come to our notice that the homeowners who have been running retail businesses on their own house have left this business.”

According to the Food Grocery Trading Association Nepal President Devendra Bhakta Shrestha, retailers have gone missing after borrowing large quantities of goods from wholesalers. “It has been seen that there is a crisis in the business,” views Shrestha.

No records

The local governments where such businesses are registered have shown indifference about this plight of the retailers. The Kathmandu metropolitan city (KMC) has stated that there is no integrated information on how many businesses have been registered and how many have been displaced.

Basanta Acharya, the KMC information officer, says that there is no integrated information on the number of retail businesses registered at the ward office. Even the Revenue and Tax Department of the KMC does not have the details of such businesses.

Shiva Raj Adhikari, chief of the department, says that such details could not be confirmed as small entrepreneurs were not forced to come under the tax net.