Padma Belal from Doti in the Sudurpaschim province of Nepal got married to Gopal Belal when she was just 17 years old. Soon, the two gave birth to their first child – a girl. In the next six years, the couple conceived three other children.

To support his family, Gopal then decided to go to India to find work as he had known many Nepalis in India. He said he would go to India, work a few months, come back and spend time with his family. Accordingly, one day, he left his family, including his five-month-old daughter, to work in Punjab and never came back.

It has been 14 years since he disappeared. In this time, all her daughters have grown up. There has been no phone call or a letter. But, Padma still has not lost hope.

Gopal is not the only one from the province who has not returned after leaving for India for work. According to Needs Nepal, an NGO working for migrant workers, 18 people from KI Singh rural municipality alone have gone missing in India over the course of the past decade. Similar examples of Nepalis missing in India can be found in other parts of the country too.

What is odd is the government, which puts in an effort to search for people lost in the Gulf or Malaysia, has done nothing to look for Nepalis missing in India. People who have lost their family members in India say that the government does not care about them. Many feel the government thinks that Nepalis missing in India are second class citizens that hardly contribute to the country’s economy.

Different stories, similar plot

A part of Padma has given up hope, but there is a small corner of her heart that still feels that one day Gopal will come back.

“The past 14 years have been hard. I’ve spent most of it taking care of my children and mother-in-law. But, there is part of me hoping that he will return because I don’t even know if he’s dead or alive and that is what’s eating me alive every day,” says Padma, who still has not wiped her vermilion from her forehead.

She has not even asked the police for help. She did not know she could do such a thing. A few years ago, a local, Keshav Nath, took Gopal’s photo to the police. But, Padma does not have much hope from the police.

“I don’t know where he took it. I don’t know where to go because I know that without money, nothing will happen,” says Padma because all she has is Gopal’s citizenship certificate. “I don’t even have his picture.”

She says that she has heard that the chief minister of the Sudurpaschim province, Trilochan Bhatta, is from her village but adds that no help has come from him or the provincial government.

—

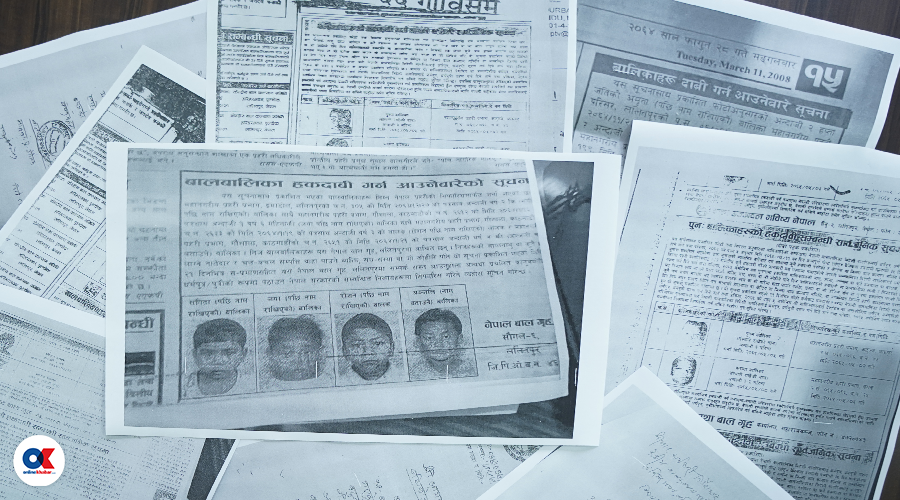

When Priyanka Kaphle from Purawas municipality went to the police asking them to find her father, one among many Nepalis missing in India since 2009, they told her she needed to get a letter from the local ward office along with a missing person report published in a newspaper. But, as she did not have the money, she could not approach a newspaper.

A few months ago, she saved enough money and published a report. She also got the necessary documents from her ward office, but she is yet to go to the police.

“There’s little hope that they’ll find him because thousands of Nepalis missing in India are not found yet, like my father. But, what’s disheartening is that the government puts an effort to look for Nepalis lost in countries abroad but when it comes to India, the case is different,” says Kaphle.

The missing role

Kaphle and other feel that it was about time that the government stepped up its efforts to find Nepalis missing in India. She says that the government should start collecting the names of people, like her father, and give it to the Nepali Embassy in New Delhi. She also calls on the government to support the families of Nepalis missing in India because many families are in shock even to this day.

Take Bhakta Bahadur Sunar’s family for example. Bhakta Bahadur’s son, Sunil, left for India when he was just 14 without informing his family.

Bhakta Bahadur, after finding out that his son had been influenced by one of his relatives, went to the police and complained. Police arrested the relative but released him after the former agreed to look for Sunil. But, to Bhakta Bahadur’s dismay, that did not happen and he went back to the police who asked Bhakta Bahadur not to bother them anymore.

Local leaders also asked him to stop bothering the person who influenced his son to go to India, after which Bhakta Bahadur, with printed photographs of his son, left his home taking the route Sunil took on his way to India.

He did everything in his power including publishing his photographs in Indian newspapers. But, nothing came out of it.

“I did everything, but I couldn’t find my son. It’s been 12 years, but I’ don’t even know if he’s alive or dead. It is very disheartening,” says Bhakta Bahadur, adding he has spent in excess of Rs 300,000 to find his son in this time.

While his elder son disappeared in India, his younger one committed suicide which has broken Bhakta Bahadur completely.

To support them, the government has done nothing.

The loss of a direction

The worst thing: the government even does not have a number of Nepalis missing in India currently. While the federal government has pretty much said it is not bothered, the local and provincial levels also seem disinterested even though these people are the support system of their families.

This was highlighted by a study on Nepalis missing in India, done by Needs Nepal. In the report, the organisation wrote that 218 Nepalis missing in India are from the Kanchanpur and Doti districts of the Sudurpaschim province. The highest number was from Sikhar municipality in Doti. Some of these people had been missing for nearly a quarter of a century.

Needs Nepal says that the number of Nepalis missing in India might be quite high if you take the entire province. An official from Sewak Nepal, Rawi Kanta Pant says no one has the correct data of people going to India in search of work, and it is the main reason why no one can find the number of Nepalis missing in India.

“The embassy doesn’t know how many people are there nor does Nepal’s government. When that happens, it makes it near impossible to find Nepalis missing in India,” says Pant. “That is why we don’t know if these people have died or have gotten arrested.”

He calls on the local wards of the province to collect data of people who are in India looking for work or are looking to go there.

“With so many people going to India for work and getting lost there, we need to start this practice. If data of people going to the Gulf or other places are kept, why can’t the government do the same for people going to India,” Pant questions.

The National Human Rights Commission province office chief Mohan Dev Joshi also calls on the government to be responsible to its citizens.