Even amid the exciting rush to the federal and provincial elections, the 27th meeting of the Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC (COP27), also known as the United Nations Climate Change Conference, created a hullabaloo in Nepal in the first two weeks of November. Reportedly, at least 76 Nepalis reached Sharm El-Sheikh in Egypt to attend the event, and most of them did not bother to come back home early to vote on November 20 as the COP27 could not conclude on the scheduled date of November 18.

Parallel to that, Kathmandu also saw some discussions and events about Nepal’s climate concerns. Not only the environmental stakeholders, but even the general public knew from the media that some important event was happening in Egypt and Nepal was also a part of it.

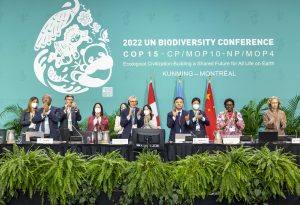

Two weeks after the end of the climate COP27, the global environmental community is looking forward to another COP (conference of parties). It is the 15th meeting of the Conference of Parties of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD), popularly known as biodiversity COP15. But, Nepal’s environmental community, it seems, looks distant from it. Kathmandu did not see any event about the biodiversity COP15 except closed-door preparatory meetings hosted by the Ministry of Forests and Environment. Neither is anyone from NGOs and the activist community attending this.

Yet, the government is sending a delegation–apparently not as big as the climate COP–to the biodiversity COP15 being held in Montreal, Canada, on December 7-19. Along with the apathy shared by stakeholders at home, the delegation members as well as experts are not confident of how beneficial the event will turn for Nepal.

A low-key issue

Until a few years back, forestry would be at the centre of environmental discussions in Nepal as the government popularised the slogan–Hariyo Ban: Nepalko Dhan (Green forests are the assets of Nepal). But, recently, climate change is replacing that position thanks to its widespread impact on different sectors.

Whereas increased awareness of climate change is completely desirable, stakeholders lament why biodiversity takes a back seat. “The notion of Hariyo Ban: Nepalko Dhan was realistic; natural resources, biodiversity included, are assets of Nepal,” conservation activist Shristi Singh Shrestha says, “If you want to make Nepal prosperous, there’s no way you can forget this.”

But, with the heightened conversations about climate change, Nepali stakeholders–including government officials–began to break apart the environment into different sectors such as biodiversity, climate change and forestry, forgetting a thin line between them, and it created a problem, comments Shrestha.

Abhishek Shrestha, a co-founder of the Digo Bikas Institute, a climate change research organisation, adds climate change is the biggest environmental concern in Nepal as several international organisations concentrated their resources on the sector. “Maybe the biodiversity COP15 is lacking promotion because the sector lacks sufficient resources,” he comments.

Meanwhile, climate change activist Shreya KC thinks biodiversity, as a field of discussion among the public, could not get as exciting an attraction as climate change because many global celebrities raised concerns about the latter. “Celebrities across the world spoke something about climate during the climate COP; this may not be so around the biodiversity COP15,” says KC.

All three activists share the biodiversity COP15 should work towards bridging such a gap between climate and biodiversity and reassert their interdependence.

Former agriculture secretary Krishna Prasad Acharya, who worked for the Forests and Environment Ministry for most times of his bureaucratic career, thinks the government is also responsible for biodiversity not getting the required amount of attention. “We [the ministry] had neither the sufficient budget nor a specific unit to look after biodiversity. As the country adopted the federal model of governance in 2017, we established a biodiversity division within the ministry, and it is trying hard to make it a priority.”

The division head Megh Nath Kafle, who will also lead the Nepali delegation to the biodiversity COP15, meanwhile, says, “Biodiversity is still a major priority of the government. We are very much active about biodiversity conservation.”

Hopes and fears

That is why Kafle hopes the biodiversity COP15 will be instrumental for Nepal to help it secure more resources from the international community based on the progress Nepal has made so far. “We will tell them how we progressed in meeting our previous commitments and lobby for performance-based financing.”

Acharya comments that Nepal planning to advocate for performance-based financing is a good idea. Yet, he does not have high hopes.

“We [the nation] are not completely prepared for such negotiations. After all, the biodiversity COP, just like the climate COP, is also a formal proceeding, and actual negotiations take place way before that,” he says, “But, we forgot that.”

He is right. In most global events, the participating delegations come with common agenda to raise in the main event so that they can create pressure on opposing sides. “For example, we could have also allied to African countries to raise our concerns about human-wildlife conflict.”

Kafle concedes the government failed in backdoor negotiations ahead of the biodiversity COP15. Yet, he has some plans, “Before the COP actually begins, we will have meetings of the working groups to finalise the agenda. On the sidelines, we can also meet other countries and forge an alliance.”

But, Acharya criticises that the ministry did not appear energetic in its preparations. “They did not even bother to update the position paper that was prepared in September 2021 for the first part of the biodiversity COP15.”

Keeping money in mind

One of the major purposes of the biodiversity COP15 is to endorse the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework that is postponed since 2020. Rounds of meetings have already been held to finalise the draft, but it still has many brackets. The last working group meeting was held in Nairobi, Kenya, in June. But, thanks to a lack of preparations, Nepal did not get much from it.

As in the climate COP, one of the biggest concerns in the biodiversity COP is financing, and it was a major bone of contention in the Nairobi negotiations also. Nepal, as a financially under-resourced country, should be tactful in this situation so that it can make the most out of it, advises Acharya.

Similarly, Digo Bikas Institute’s Abhishek Shrestha suggests the government use the forum as an opportunity to showcase its conservation success stories so that it helps Nepal’s biodiversity gain more attention across the globe.

“But, I don’t think our delegates fully prepared for this,” said Acharya, who attended some of the recent meetings held by the ministry about the biodiversity COP15 preparations, repeats.

So, there is no guarantee that Nepal will surely reap benefits from the Montreal meeting. Even Kafle himself is not confident. “Everything will depend on the atmosphere there. Yet, we will try our best to raise our voice for securing bio-finance.”

“I hope we will be able to make the biodiversity COP15 decide something that favours Nepal.”

This story was produced as a part of the 2022 CBD COP15 Fellowship organised by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.