When one species encounters another, also occupying the same habitat, splitting up the resources available can help avoid competition. This is the strategy adopted by gharials and mugger crocodiles in Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary in northern India, according to a study by researchers from the Wildlife Institute of India, which finds that both species have different preferences for basking and nesting sites.

Classified as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), gharials (Gavialis gangeticus) are long crocodiles native to northern India and are distinguished by their long, narrow snouts. In contrast, the broad-snouted mugger crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris), also known as marsh crocodiles, are vulnerable and have a wider distribution extending into Pakistan and southern Iran.

Both species have overlapping habitats in the northern rivers (Ganges, Chambal, Son, Ramganga and Girwa) and eastern (Mahanadi) river systems of India and historically have shown systematic resource partitioning in their aquatic environments, said B.C. Choudhury, co-author of the study and retired professor from the Endangered Species Management Department at the Wildlife Institute of India.

“The gharial is predominantly a fish-eater but mugger is very catholic in its dietary choice (having a diverse and broad diet). In their natural riverine habitats, the gharial numbers were higher than mugger,” he said.

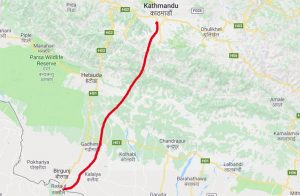

Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary (KWS) is situated in northern Uttar Pradesh close to the Nepal border, where populations of both species were enhanced by the reintroduction of captive-reared stocks, said Choudhury, who is also a member of the IUCN-SSC Crocodile Specialist Group and its regional (Asia) co-chair.

“In the first few years, the reintroduction was only of gharial. But while the wild-laid gharial eggs were collected for artificial hatchery incubation, mistakenly, mugger eggs were also collected and hatched in captivity and after rearing they too were released into the protected area,” explained Choudhury. “Being hardy and adaptive, the mugger population increased faster compared to the gharial and this mugger reintroduction has been a cause of concern. This mugger release has been happening since the mid-1980s.”

But until now, little is known about how these two crocodilian species partition resources in terms of basking and nesting. To find out, B.C. Choudhury along with Shikha Choudhary and Govindhan Veeraswami Gopi surveyed gharials and muggers from December to April 2011 along a 14-km stretch of the Girwa River that originates from Nepal and flows in the north-west of KWS. They identified where both species bask and nest focusing on variables that affected their preferences for these sites such as slope, height, soil moisture, among others.

Different site preferences for nesting and seasonal basking

The researchers found that during winter and summer, gharials preferred to bask on mid-river sand islands known as sandbars and on gentle slopes, at a lower platform height whereas muggers basked mainly on river banks choosing steeper slopes and elevated platforms. This is likely because gharials have weaker legs, the team said. “Unlike muggers who can walk high, gharials can only crawl,” said Shikha Choudhary, lead author of the study, which was her Master’s dissertation at the Wildlife Institute of India.

Gharials picked basking sites with higher soil moisture than muggers. “Gharials being of lighter colouration need more heat to warm their bodies,” explained Choudhary, and “sandbars, or sand and silt” have “far more moisture than other surfaces” providing “a combination of hot (sunny) and cool (from moisture in the sand) environment, reducing the chance of desiccation while basking.” It is also easier to descend back into the water from sandbars. Muggers, on the other hand, were not restricted to sandy surfaces and were found basking on a variety of substrates such as silt, clay and fallen logs.

When it came to selecting nesting sites, gharials and muggers had very different choices. While both species lay eggs in the dry season, gharials picked sandy soils that were closer to the water with steeper slopes and higher height, whereas muggers chose sites farther away from the water with gentler slopes and a lower height.

A possible explanation for gharials nesting closer to the water may be because unlike other crocodile species in which parents help their hatchlings emerge from the nest and carry them to the water, gharial hatchlings have to reach the water by themselves, said Choudhary, who is currently pursuing her Ph.D. at Amity University. “Since nests are very close to the water, gharials prefer steeper sandbanks mainly to protect their nest from the fluctuating water levels of the river.” Also, by placing nests higher and on sandbars, gharials are able to avoid predation, added B.C. Choudhury.

Gharials more vulnerable, muggers thriving

This study seems to suggest that “gharials are specialists in selecting basking and nesting sites, while muggers are generalists,” said Choudhary, adding that “because of this, gharials are more vulnerable to any changes in habitat.”

To reduce competition between the two crocodilian species, the researchers suggest that conservation efforts should pay attention to gharials in north Indian rivers while in peninsular rivers, muggers should be the focus.

Choudhary warned that “de-siltation of the river or deepening of the river” could lead to the elimination of mid-river islands” or affect the course of the river, which can, in turn, have an impact on gharial nesting sites.

“This is an interesting study that separates habitat requirements of gharial and mugger in the same habitat,” said Lala A.K. Singh, former officer-in-charge of the Government of India CCBMTI (Central Crocodile Breeding and Management Training Institute), who was not involved in the study. “They have quantified it to a certain extent,” he said, adding that “this will guide the managers and researchers” when incorporated with his past findings. In a 1991 report from the Mahanadi, he observed that “with disturbance, gharial, may desert a place but mugger may thrive and ‘prosper’.”

Additionally, Singh pointed out a recent concerning trend he has observed: mugger populations are increasing in some gharial habitats. In a 2015 study he co-authored with Rishikesh K. Sharma from the National Chambal Gharial Wildlife Sanctuary, which houses the country’s largest population of gharials, Singh noted that over a period of 30 years from 1984, mugger sightings have shot up “more than 10 times from 33 and their spatial distribution has expanded to the entire river.” But during the same time period, “sighting of gharial has increased less than two-fold from 605,” he revealed.

“Gharials have specific habitat requirements; so they do not leave perennial river habitats,” explained Singh. “In the long past, mugger could have taken over some habitats completely—in south / central India (Narmada river, is one example); Mahanadi is the recent example. Chambal appears to be going that way.”

CITATION:

Choudhary S., Choudhury B.C., Gopi G.V. (2018) Spatio‐temporal partitioning between two sympatric crocodilians (Gavialis gangeticus & Crocodylus palustris) in Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, India. Aquatic Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst, 1–10. doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2911

This story was first published on Mongabay. Read the original story here.