Kathmandu, in the 1980s, was a growing city. As its population started to increase, a lot of problems arose. One of them was the lack of clean drinking water.

To curb the problem, a project was envisioned in the 1980s. The project aimed at bringing water from the Melamchi in Sindhupalchok to Kathmandu. The project was inaugurated in 1998 with the first phase to be completed a decade later. But, nothing went as planned as the project only took off properly in 2007. Even though Melamchi’s water has started to come to Kathmandu after 23 years, the project is yet to be fully completed.

This is just one example of a national pride project being kept in limbo. Almost none of the national pride projects are completed on time. A reason for the delay has been political leadership and bureaucracy that feel putting projects in limbo helps them earn more. The political leadership does not want to take ownership while the bureaucrats create a bubble where everything goes in the loop. This has wasted both time and taxpayers’ money preventing people from benefitting from these pride projects.

Here is a list of 12 pride projects which were and are in limbo and the reasons behind it.

1. Sikta Irrigation Project

It has been 45 years since the pre-feasibility study on the Sikta Irrigation Project was done. As of April, only 65 per cent of the project has been completed. Even though preparations for the projects were done well beforehand, the governments never set aside the budget to carry out the project. The government, however, in 2005, decided that it would invest its own funds and workforce to carry out the project. The project then started in 2007.

The reason that the project has not been completed in time, according to project insiders, is the lack of funds allotted to the project.

Ironically, this is the same project where the embezzlement of Rs 2.13 billion led to a case being filed against former minister Bikram Pandey and 21 others. The case is still being heard at the Special Court where four former chiefs of the projects have been accused of corruption.

The contractor for construction, CTC Kalika Joint Venture Pvt Ltd, is also under probe for undertaking below-par works for the project. Pandey is also the owner of the construction company.

The project now is not moving forward as it lacks a skilled workforce that includes surveyors and enumerators.

According to the 57th annual report of the Office of the Auditor General, there are serious problems with the western part of the canal. But, the contractors have already taken money to construct the canal on the western side. The canal near the Changai Nala area is in dire need of repair, but as of April 2021, no effort has been put forward to repair it.

The project’s cost has increased to Rs 25.2 billion in 2021 from Rs 12.8 billion initially.

2. Babai Irrigation Project

The International Development Association (IDA), a body of the World Bank, did a pre-feasibility study in 1975, after which the irrigation project took shape. Like the Sikta Irrigation Project, Babai Irrigation Project is also 45 years old, but only 51 per cent of the work has been completed as of April 2021.

The feasibility study for the project was done with the help of the UNDP in 1977 and 1980. In 1981, a design was made with the help of the IDA, after which a 5.5-kilometre long canal was constructed where water had started to flow in 1994.

According to a report prepared by the National Planning Commission, the canal should have water for seven months a year. The rest of the year (five months) has been kept for canal repair and construction. This, the people involved in the project have said, is one of the reasons that the project has not been completed on time.

But, there are other problems as well, including those regarding the acquisition of land due to social and legal constructs. The project area falls under the Bardiyaa National Park. This has made things difficult such as bringing in machinery and resources to construct the canal. The lack of resources to construct the canal is also creating a problem, say officials.

The cost of the project which was Rs 2.87 billion in 1975 has now gone up nine times and reached Rs 18.96 billion.

3. Rani Jamara Kulariya Irrigation Project

The Rani Jamara Kulariya Irrigation Project is 100 years old. The project, which was the brainchild of a local Tharu farmer is the Karnali province’s largest irrigation system. The efforts to make the irrigation system modern is, however, going at a snail’s pace.

The project aims to irrigate over 38,000 hectares of land, which the government only started to include in its budget from the fiscal year 2010/11. It is a reason only 48 per cent of the work has been completed.

The project chief Kedar Kumar Shrestha says the source of the canal falls in an unregistered arable land where people have been living. This has made it hard to acquire the land for the project. Almost all land needed for the project is unregistered and arable, says Shrestha, who adds that most of the land has been encroached upon by locals.

The locals of Chisapani and Lamki, according to Shrestha, are the ones who are encroaching on the unregistered and arable land needed for the project. The project has already handed out compensation. But, in Lamki, the project was affected for a while as it needed to cut trees in the national forest area.

The project also faces problems related to low bidding. Shrestha says that right now there are five contracts set aside for foreign companies and 27 contracts for Nepali companies. Almost all of the contractors have bid lower than they were supposed to and have received the contracts.

“The Public Procurement Act forces us to give the contract to the lowest bidder,” says Shrestha. “If we give it to the highest one, people will say we took a hefty commission.”

Like the abovementioned projects, the budget of the project has also increased twofold to Rs 27.7 billion from Rs 12.37 billion.

4. Mahakali Irrigation Project

The project that started in 1981 is currently in its third phase which started in 2006. The project aimed to irrigate over 33,500 hectares of land in the Kailali and Kanchanpur districts. But, only 39 per cent of the work in the project has been done so far. The estimated cost of the project is Rs 34 billion.

According to the National Planning Commission, the main problem with the project is the delay due to compensation issues. Like the Rani Jamara Kulariya Irrigation Project, most of the land needed is in unregistered arable land. Nepal’s law says that the government will not provide compensation to people living on the land. But, locals say they have been living there for generations, hence they need to be compensated if the government wants to use it for the national pride project.

The Council of Ministers is yet to come up with a decision as to what to do in such cases. Until it can take a stand, the completion of this project is in serious doubt.

The sad state of the project can be seen in one example. The project, which had promised to plant 10 trees for every tree it cuts down, is finding it hard to purchase land to do so. Apart from that, the lack of human resource and unplanned river extraction is also causing problems to complete the project on time.

5. Bheri Babai Diversion Multipurpose Project

While doing the feasibility study of the Babai Irrigation Project by the UNDP in 1977, plans were also made about a diversion project in the area. That plan materialised with JICA in 1992 while studying the multi-dimensional use of water resources in the Karnali and Mahakali river basins as the officials felt that it could happen and put the diversion project in priority.

In 1998, JICA conducted a feasibility study, and in 2008, the project was given a green light by the Department of Irrigation. Since then, only 40 per cent of the project has been completed. Even though the project had received widespread appreciation for completing the 12.2 kilometres in a short time, little progress has been made since then.

Like in other projects, the planning commission has said that the delay is due to difficulty in acquiring land owned by people and forest committees. The project also needs to cut down trees, but it is not being able to coordinate with government agencies.

The Council of Ministers had given the project permission to use the 5.42-hectare forest area to construct headworks, access tunnels and other infrastructures. But, for that to happen, it needs to cut down 1,023 trees, which it can only do upon receiving permission from the Forest Ministry.

The only thing that is complete is the 12.2-km long tunnel. But, the construction of a powerhouse for the 46.8 MW hydropower project is being done at a relatively slow pace. The initial estimation for the project was put at Rs 16.43 billion, but now due to the pace of the project has gone up to Rs 33.19 billion.

6. Budhigandaki Hydropower Project

The date for the construction of the proposed 1,299 MW hydropower project is yet to be finalised. The government has given Chinese company Gezhouba Water Group the responsibility to handle the project.

Even though the plan to construct a hydropower project was made in 1989, the government has only started to set aside a budget since the fiscal year 2012/13. Since then, the project has handed out compensations to locals of Gorkha and Dhaging whose land will be submerged underwater. As of April 2021, a total of Rs 33.6 billion has been handed out as compensation. A total of 3,000-hectare land needs to be acquired for the project.

The planning commission says that even though there is a budget, the government has not been able to hand out compensation because the compensation rate is yet to be determined. Relocating the people from the project site and problems arising due to the valuation of land during compensation has been cited as reasons for the lack of progress on the project. The government is also unaware of how to build such a big project and where it can manage Rs 260 billion it needs to complete the project.

7. West Seti Hydropower Project

The West Seti Hydropower Project was envisioned by 1980 as a run-of-the-river hydropower project which would produce 37MW electricity. The company that visioned the project, Sograha Consultant, did another study in 1987 when it found a way to increase the capacity of the project to 360 MW by adding a reservoir. The environmental assessment study of the project had been done in 2000, but since then, the government has been signing contracts with various companies cancelling it later on.

The total estimated cost of the project is Rs 273.85 billion as it aims to now produce 1,200 MW of electricity. No work has been done on the project nor has a date been set for its commencement even though the government has been setting aside a budget for the project since the fiscal year 2011/12.

8. Pokhara Regional International Airport

If you look at the history of the project, you have to go back 40 years. The land where the airport is currently being constructed was purchased in the 1980s. But, the project only took off in 2011. That said, it took the Nepal government six years to finalise a loan from the Chinese government to start the project officially in 2017. The agreement between Nepal and China states that the project will be completed at the end of 2021. But, the chances of that happening are very slim.

The aim is to build an airport that will come under the ICAO’s 4D standards. Rajan Pokharel, CAAN’s director-general, says efforts are underway to make sure that the project is completed on time. But, due to Covid-19, things moved at a slow pace in 2020 as most Chinese workers who were an integral part of the project returned home.

The planning commission says that work still needs to be done for bringing a dedicated electricity line into the airport along with setting up a fuel depot. For that to happen, the project needs to acquire more land, say people associated with the project, but locals have been unwilling to agree on the set compensation. The total estimated cost of the project is Rs 21.6 billion.

9. Nijgadh International Airport

In 1995, a consulting firm, NEPICO/IRAD conducted a pre-feasibility study on eight areas of Nepal to recommend the best site for a new international airport. Based on the geographical location, topography, distance to the largest cities, road accessibility, forest density and airspace; NEPICO/IRAD suggested Tangyabasti, near Nijgadh, and its surrounding forest area to be the most appropriate site for the construction of the airport.

In 2007, the planning commission even asked the government to set aside a budget to construct Nepal’s second international airport. In 2008, the government asked a Korean company to compile a detailed feasibility report. But, the government has not been able to move the project further.

According to CAAN’s director-general Pokhrel, the project is yet to determine a modality and clear the site for construction.

Work also has to be done in regards to relocating Tangyabasti. “We’re still counting the trees we need to cut down. The project hasn’t got the approval to cut down the trees.”

The government has started to set aside a budget for the airport since 2014. But, the future of the project, due to constant criticism, is still in doubt. The estimated cost for the first part of the project is around Rs 165 billion.

10. Pushpalal Mid-hill Highway

In the National Transport Policy 2001, a proposal to set up a new highway as an alternative to the East-West (Mahendra) Highway was put in place. The government started to take the proposal seriously and set a budget for it in the fiscal year 2007/08. The highway would be 1,879 km long and would have 121 bridges.

However, the project, which aims to make the lives of over 10 million people better, to date, has only been half done.

Like in all pride projects, the planning commission says that compensation is one of the reasons why the project has not been completed. The other, it says, is having trouble identifying road borders.

There are a few areas where the highway has been forced to divert itself due to it being in the way of hydropower projects. Other than that, the project has also suffered due to the lack of resources for the construction of the highway.

The officials of the project also say they also have trouble with the process of cutting down trees and relocating the electricity poles and drinking water pipes that are on part of the places where the road expansion needs to take place.

The initial cost of the highway was estimated to be Rs 33.36 billion, but now, it has increased to an unprecedented Rs 101.5 billion.

11. Melamchi Drinking Water Supply Project

Melamchi Drinking Water Supply Project is another project which was in talks for a long time. Even though the plan to start the project was made in the early 90s, it started to take shape in 1998. Even though the project has somehow materialised, it is yet to be fully complete.

Currently, the project is in its testing phase as it is trying to identify leakage areas. Upon completion, the project aims to send around 17 million litre water daily to Kathmandu.

The project in the past decades has received additional time on a regular basis. But, after Italian contractors CCMC left, the project has been divided into 10 parts. But, coordination among the contractors in these 10 parts is still an issue, claims the planning commission.

Work has also been affected by Covid-19 while a modality regarding profit sharing is also yet to be made. The project has also not addressed the demands of the locals.

The cost which was put at Rs 17.43 billion has now nearly doubled to Rs 31/36 billion.

12. Lumbini Area Development Trust

In 1977, the government developed a master plan to develop Lumbini, the birthplace of Lord Buddha. The master plan was later turned into a national pride project. But 42 years on, the visions on the master plan is yet to become a reality even though it should have been complete by 1996.

An auditorium, eight cultural buildings, a water tower and a supply system, a road along with the vihar areas, a pond and various other monuments were supposed to have been made by then.

Apart from that, excavation in areas like Tilaurakot, Gotihawa, Niglihawa, Devdaha and other areas related to the birth of Buddha was also in place. Around 85 per cent work of the project has been completed.

The planning commission says that work would have been completed on time had international donors given the trust the pledged amount. The estimated cost when the project commenced was Rs 5.55 billion, which has now increased to Rs 6.10 billion.

Rs 300 billion cost added

Due to the delay in the completion of these projects, the cost has increased significantly. According to data, the 12 pride projects which are over two decades old have now cost Nepal Rs 300 billion extra. The money, experts say, could have been used to complete a dozen other new similar projects.

Same problems everywhere

The National Planning Commission in its yearly meeting has tried to analyse why these projects are facing similar problems which include being given a budget without proper planning and difficulty in acquiring land.

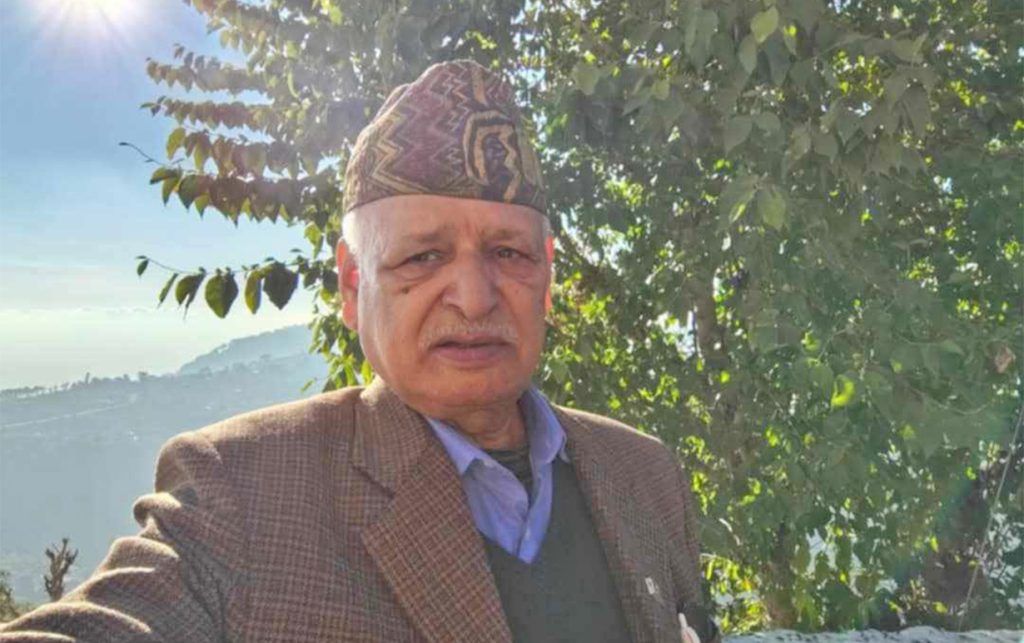

A former vice-chairperson of the commission, Govinda Raj Pokharel, says mismanagement, bad choices regarding contractors, the lack of skilled workforce and other resources are major problems why these pride projects take time to complete.

He says that the government needs to get better in the management of such projects. He says that if the government treats the project with importance, the projects will be completed right on time.

Longer the project, the more benefit for those involved

Min Bahadur Shrestha, another former vice-chairperson of the commission, says that most of the problems are just excuses to extend the projects. “These are national pride projects but sadly no one treats them like one.”

He says the pace of these projects started to slow down after the reestablishment of multiparty democracy in 1990. “The government started to look at how the money was being distributed instead of looking at how efficient infrastructure development could be.”

This resulted in small projects getting more importance than the pride projects put aside citing the lack of budget. Even though newly elected governments announced ambitious pride projects, the implementation has been extremely poor, according to experts.

Shrestha says most of the projects which are being worked on were envisioned either in 1990 or before it.

The current government, however, in its five-year plan, has said it will try to finish most of these pride projects by 2024. The commission’s current vice-chairperson Pushpa Raj Kandel says that the commission is going to do everything it can to ensure that these projects are completed on time.

But, looking at how things have been in the past, chances of that happening are slim, say experts.

“If work was done based on the plans, none of them would have taken over two decades to complete”, says former finance secretary Yubaraj Bhusal.

He says that political parties see these pride projects as the geese that lay the golden eggs.

“Why would they want it to stop when they can keep on hiring their own people and receive the reward?” he says. “As long as this lasts, projects will continue to go in limbo.”