In August 2015, a 45-year-old woman from Surkhet of Karnali province approached the Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital with ‘unusual’ complaints. The patient was tired after visiting hospitals in Nepal and India for the past few months–none could diagnose her condition.

Most doctors she visited had told her that she had cirrhosis (scarring of the liver), but medication to fight the ailment had not worked. Finally, an investigation by a specialised team at the TUTH not only identified the disease but completely got rid of it in two weeks.

“This was the first properly confirmed case of human fascioliasis in Nepal,” informs Dr Ranjit Sah, infectious disease specialist at the Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medicine, TUTH. “Though this was the first confirmed case, research shows the disease has been prevalent among Nepalis for decades. So far, total 12 human fascioliasis cases have been identified though only two were reported internationally.”

Dr Sah, one of the handful of professionals who know the existence of the disease in Nepal, points to a problem which is many-fold serious than the ailment itself: most doctors do not know about this ailment and hence diagnose it wrong–most often as cirrhosis or liver cancer.

“I think we need to educate doctors and other health personnel first to save patients from this chronic suffering,” he argues.

So what is it?

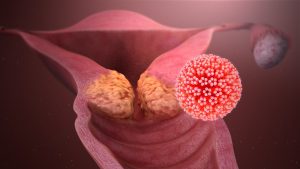

In the simplest terms, human fascioliasis is a medical condition in which worms named fasciola hepatica or fasciola gigantica find their way into the human body. This is a zoonotic disease; it spreads between animals and human beings.

“In the case of Nepal, the original source of this disease are cattle at our farms,” Dr Singh explains, “However, they do not directly transmit the disease. It comes to human beings through water and other aquatic plants.” It means people who consume aquatic plants and rear cattle are more prone to the disease.

When cattle drink water from rivers and ponds or graze on the banks, they leave fasciola worms in water and grass as they excrete their faeces there. The worms then find their place in roots of aquatic plants which human beings consume as vegetables and salad.

How do humans get infected?

According to Sah, a sizeable rural Nepali population regularly consumes watercress (simsaag in Nepali), as a form of curry. The grass is likely to carry worms if not cooked properly in heat above 60 degree centigrade. Drinking water directly from rivers and ponds where cattle also drink from may also result in the worm getting into the body.

“Then, the worms lay eggs in intestines. These eggs produce adult worms, which block the bile duct which connects the liver, gallbladder and the intestines. This is when you experience many usual and unusual health problems including jaundice, fever, and stomachache among others.”

Besides the lack of knowledge among the general public and medical professionals themselves, another problem in diagnosis of the disease is the apparent variation in the time the worms take to show up. “While in some cases the symptoms are there as early as six months after the eggs are laid, some people do not seem affected for 10 to 15 years,” Dr Sah says.

Apparent symptoms are not enough to confirm the disease as they may indicate other problems too. For confirmation of human fascioliasis, doctors examine stool and if it shows fasciola eggs, the case is confirmed as human fascioliasis.

Why wrong diagnosis?

That human fascioliasis is very rarely heard of in Nepal is the greatest reason behind the fear of the wrong diagnosis.

“Parasitic infestations are common in developing countries. However, they are wrongly diagnosed as other medical or surgical conditions and remain untreated for long,” reads an article about the case of Surkhet woman in BioMed Central Research Notes. “Infections like fascioliasis can be diagnosed by simple stool routine microscopy examination and their treatment is simply a short course of anti-helminthic therapy.”

The second reason, according to Dr Sah, is the unavailability of medical equipment and technology. “We need to carry out an ERCP (Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) to fully confirm the case as fascioliasis. But, this is available only at a couple of government health facilities including the TUTH and Bir Hospital as well as a few big private hospitals in Kathmandu,” Dr Sah says.

Is right diagnosis enough?

Diagnosing the disease correctly, of course, makes it possible to administer the right medication, but it does not ensure complete cure. In the case of Nepal, the right medicine is not available.

“There are two types of medication for fascioliasis cases. The World Health Organisation recommends the first type which has a proven record of almost 100 per cent effectiveness. The second one has a history of fighting the disease in around 60 per cent cases,” Sah informs, “The first type of medicine is not available in Nepal, India and any other countries nearby. The second type is not available in Nepal, but is available in India.”

Dr Sah’s team has been applying the second type of medicine to patients so far. In the meantime, they are lobbying with the WHO to ensure easy access of patients to the best possible life-saving medicines.

But, there is yet another problem. Nepal’s emerging problem is yet to blip on the global health agency’s fascioliasis prevalence map. Sah says he, however, has reported two Nepali cases to the WHO headquarters in Geneva by publishing articles in international health journals.

“These journals will help Nepal get the WHO support for combating fascioliasis officially,” he suggests, “But again, the government has to take initiatives for greater changes.”

As of today, the government has not done anything about the disease, Dr Sah claims, adding there might be no one official at the Ministry of Health who knows about the existence of this disease in Nepal.

What are the precautions?

The golden rule that prevention is better than cure applies to fascioliasis as well. Therefore, Dr Sah suggests people be careful while drinking water and eating green vegetables. “Always drink boiled water. The source of your drinking water should be different from the ones cattle drink water from.”

“Then, cook green leaves above 60 degree centigrade,” he says, “If you cannot make sure that the temperature is right, just avoid consuming veggies collected from river banks or shores.”

Likewise, academic institutions like Tribhuvan University Institute of Medicine can also contribute by correctly diagnosing cases. Though medical students frequently read health journals to get ideas about new issues and problems, the institutions can organise other programmes to give a momentum to the discussions on the topic, according to him.

“Fascioliasis is just a case in point. There are many diseases like this that can be easily diagnosed with the right equipment,” he says, “But, awareness—among health professionals and public—is a basic necessity for both.”

Images courtesy: Dr Ranjit Sah