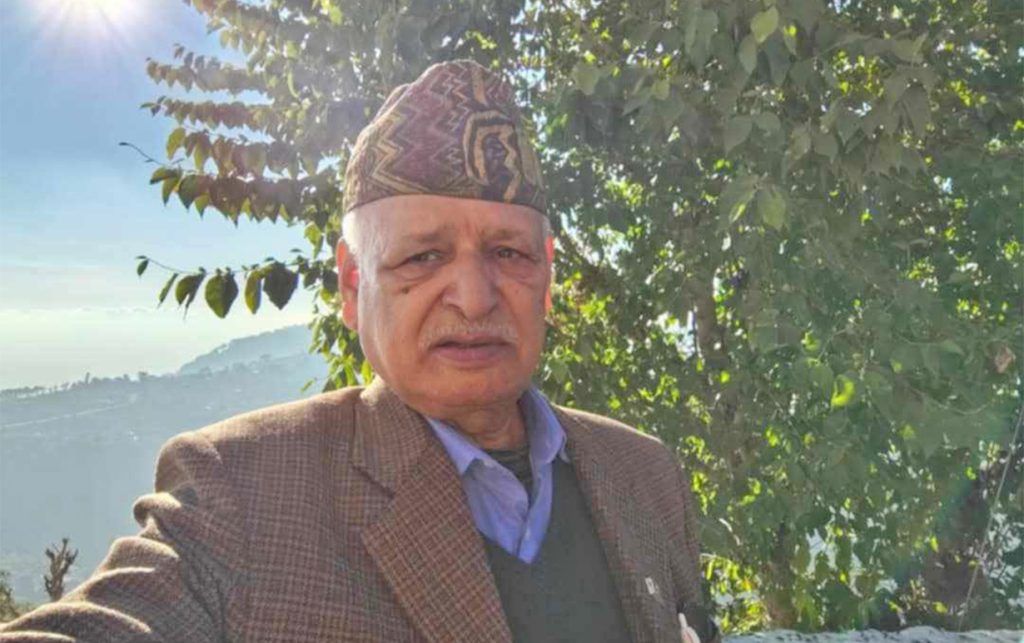

After reports of a ‘mass suicide’ by monkeys in Chautara of Sindhupalchok district came out, zoologist Dr Mukesh Chalise’s phone was abuzz the entire week. Chalise, the most quoted ‘monkey expert’ in Nepali media, retired from the Central Department of Zoology of the Tribhuvan University last month. Onlinekhabar recently caught up with Chalise, whose PhD research decades ago focused on the food habits of male and female monkeys.

Excerpts:

Let’s begin the conversation about the ‘mass suicide’ case. You told the media that animals don’t commit suicide or any other crime intentionally. What grounds do you have to support your thesis?

In the course of evolution, the primitive species developed the simplest of nervous systems, which would enable them to feel heat and cold; light and dark. Gradually, other organ systems developed and later specific parts such as nose, ears, and eyes came into being. Then, after thousands of years, mammals came into existence. Humans are mammals whose nervous system has achieved the highest level of development among all the species, and far high enough than lower species.

If you love someone, you can sacrifice your property for them. You can donate the blood flowing inside your body; you can even donate your own organ so that another person can lead a better life. Human beings don’t only have the highest level of benevolence, but also the highest level of selfishness. We can commit heinous crimes such as rape and murder. Suicides are also a result of the highest depression resulted by the influence of genetic characters, religious, social and political situation that impact on human instinct.

Though monkeys are also mammals, they cannot develop such desires because their brain is not fully developed for that. They can make efforts to save themselves and their partners, but they cannot think of killing themselves intentionally. Many animals die falling off cliffs while running to protect themselves from predators, but it should not mean that they commit suicide in fear of predators.

Many people in the Tarai report to me that they have seen many langurs falling off the trees to kill themselves after seeing carnivores, but it is not true. What happens in such cases is that the langurs lose balance after seeing predators and accidentally fall down.

Monkeys have a peculiar interest in investigating things around them, but humans misinterpret it as ‘mischief’. When they find new things, they check if they can eat it; when they go to any new place, they check if they can play there. In 1996, a monkey in Pashupatinath area of Kathmandu touched an unshielded wire; it received an electric shock and cried–without detaching itself from the wire. Another monkey heard the cry and came to save it; it also cried for help. In this way, a total of 41 monkeys died in their efforts to save one monkey. This cannot be considered a mass suicide case because they wanted to save their friend, but that does not mean they wanted to kill themselves.

Like other human societies, Nepali society is also living with animals for ages. But why doesn’t it understand basic things about animals and misinterpret cases like these? Wasn’t it the responsibility of academic institutions like university departments, such as the one you worked for over three decades?

In order to understand why we failed, we need to understand how our education system was developed. If you analyse the historical development of schools in Nepal, you see that our education system always concentrates on meeting the needs of the bureaucracy; this is reflected in both what is taught and how it is taught. It was not concerned with producing experts of certain disciplines or connecting sciences with society. Before the ‘new education system’ (Naya Shiksha) was implemented in the early 1970s, we were required to study ‘civic education’ (Nagarikshastra) and ‘bylaws’ (Ainshastra) in school. They were compulsory subjects, but maths and science were not. We had to learn how to prepare a ‘tamasuk’ (an agreement to facilitate local loan transactions) and how to fold a paper to write a tamasuk.

At the higher level also, the study of science began only in 1959 with the establishment of the Tribhuvan University. Among various disciplines of natural science, many people were attracted to physics because it was comparatively easier and it would not require the students to go beyond the campus. Subjects like zoology came much later, in 1965, because they were more difficult and required practical insights. In the beginning, professors from other countries would visit Tri-Chandra College to teach us. Our university [Tribhuvan University] did not conduct exams on such subjects. If you check the certificates of science professors of that time, you can find they acquired the degrees from foreign institutions including the Patna University of India. Overall, the education system focused on meeting immediate needs, it did not help address practical concerns of common people and uplift the country in the world of sciences.

So, how long did the problem exist? It must have been solved by now.

No, even our academic programmes just copied courses from Patna University. Even after I joined the university, I remember, we had to struggle to include material related to Nepal’s flora and fauna in the curricula. Intentionally or unintentionally, the professors copied from others, without considering the dignity of their own country.

So far, only around a dozen have completed their PhD in zoology from the Tribhuvan University. I did my PhD in 1995; I was the seventh Nepali zoologist to obtain a PhD and the first in my generation to do so. In the past 24 years since then, only eight persons have done their PhD in this field from the TU. Some went to foreign universities.

Exactly! The number of science students at the high school level has significantly increased. But most of them study medical science or engineering. No one is willing to take up zoology or botany.

Many students, who studied zoology at the master’s level, did not continue their study in the field, but joined the civil service. Former chief secretary Bimal Koirala; and former secretaries Bal Krishna Prasain, Madhu Raman Acharya, BHoj Raj Ghimire, Sushil Ghimire and Mahashram Sharma studied zoology. But they left the discipline after realising that the civil service did not have any position for zoologists. The Public Service Commission calls applications for various positions that require people who have studied accounts, statistics, forestry, geology, or medical science, but not zoology.

Even the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation did not accept us. From its inception, it decided to recruit people who have studied forestry. They though zoologists know about animals, not about the forest. All high position holders of the department are students of forestry. They continued to ignore zoologists.

The zoology department of Tribhuvan University has so far produced around 1,000 zoologists; around 100 have completed their PhD from foreign universities. But still, the Public Service Commission does not recognise the discipline.

Of late, some national and international nongovernment organisations have begun looking for zoologists. Our students have achieved remarkable scientific results in exploration, the discovery of species and impact assessments for developmental projects.

Maybe the commission thought the discipline did not have any importance at the government departments. After all, they are functioning okay even without the zoologists.

No. Zoology is one of the most important scientific disciplines for Nepal. We still proudly claim that we are an agricultural country. Animal rearing is a major branch of Nepali agriculture system, and this is where the farmers can use zoological knowledge. Zoology gives you information about habits and behaviours, life cycles, food systems, reproduction systems and habitats of animals and birds. It means if farmers begin their businesses with the knowledge of zoology, they can reap additional benefits.

If you talk about agriculture-based industries, zoology is equally important. For example, you want to open a modern slaughterhouse. You need zoological knowledge there because veterinarian knowledge is not enough.

Zoology is important for the social sciences as well. You may know that Germans developed the kindergarten system in education after noticing that animals that were separated from their parents early could not socialise well. You can also take the Sindhupalchok case as an example here. After the incident of the deaths of monkeys, locals now need to take additional safety measures to protect their children from drowning. Studying animals has always helped the human society.

If you talk about medical science, if you can extract venom from poisonous snakes like cobra, you can use that to produce anti-venom medicines and save thousands of lives. You might know that the vaccines that are applied to human beings were first tested on animals…

Yes. But, rights activists have always protested the act of using animals to test medicines. Do you think that is ethical?

So do you want to kill human beings in order to save animals? Without causing significant loss to their number, we need to use a few animals to save humanity. Do you wish for the continuous increase in the number of leopards around Kathmandu at the cost of lives of people living there? Or do you think that is ethical?

I am clear that we need to kill animals if they cause harm to humans or other beings. As a human being, I don’t want the destruction of the human race just to increase the number of other species. I continue giving the medicines tested on monkeys to my aged parents who are suffering from high blood pressure and diabetes. If you love monkeys more than your parents, you can abstain from using the medicines. If you want your mother to die in the pain of uterine cancer because you don’t want to carry out a surgery that is tested on an animal first, that is fine. Do you know that cataract surgery started by testing it on monkeys? But if you don’t like it, fine. I don’t argue with you.

But if we develop zoological studies in Nepal, the country can earn millions of dollars every year by selling the medicines. If the country wants to capitalise on its biodiversity, zoological knowledge should be used in medical science. For example, China earns money from every panda of a particular species that is born in any part of the world because the species is originally available in China only. Similarly, macaques (known as red monkeys) that are available in Nepal are ‘purer’ than those in India or China; hence we can experiment medicines of AIDs and tuberculosis on them, and earn millions of rupees in revenues. We should move towards that model. In the name of rights, we should not promote wrong concepts and practices that avoid the value of natural resources. We also should be aware that such experiments affect only very few animals.

Fine, perhaps we can discuss the ethical concerns in another meeting. Now, I want to conclude the conversation on a positive note. Tell us something from the field that is improving.

The zoological study in Nepal has shifted from the traditional approach to the application-centric approach. TU has developed different courses for four branches of zoology; namely: fishery, entomology, parasitology, and ecology. Recently, our students have worked for hydropower projects, urban planning and forest monitoring. Our parasitologists have emerged as professors of medical science. The discipline’s scope has expanded.

Does it mean that Mukesh Chalise will not be the single source for media to talk about any zoological issue now onwards?

Haha… You need to know why I was called and quoted every time. Thanks to my family’s encouragement, I began exploring new places and study about animals living there from my youth. Before Makalu Barun was named a national park, I visited that place and carried out the research. When I submitted my proposal about monkeys to the university for my PhD, many people laughed at me. They said I could have received huge foreign grants if I had chosen elephants, tigers or rhinoceros. I said I did not need money, but knowledge.

Many things are yet to be improved in the discipline in Nepal. The discipline has to be made more practical and connected to daily life. For example, institutes of eastern Nepal should teach their students about parasites and insects affecting the tea cultivation; colleges of western Nepal should teach them about tigers and elephants. They should know why Indian elephants cross the big Mahakali and come to Nepal. The students of the Koshi region need to learn why wild water buffaloes are found in that region of the country only while similar river systems exist in Karnali, Rapti and Narayani regions as well. The students should be taught about pesticides that are applied to vegetables of this region. If that had been the case, our students would have tested pesticide residue on the vegetables imported from India even if the government did not care about it.

This is a global practice and we should follow that. We should thoroughly overhaul the university curricula. Otherwise, the degree you have earned only serves as your prestige label.