When people talk about Ramayana, one of the greatest Hindu epics, most of the times you are likely to hear about, among other things, the wedding of Ram and Sita. People talk about their grand wedding in quite a detail, but a part of the nuptial ceremony always gets little to no appreciation among the audience.

It is said that for the holy matrimony, King Janak, the father of Sita and ruler of Janakpur [Nepal], ordered a large mural that spread from Janakpur to Ayodhya [India].

This is today referred to as the origin of Mithila art. This unique art form, common in Terai of Nepal and northern India, has had an arduously long journey for survival and recognition. Even today, people have mixed opinions regarding what Mithila art really is about given how less one knows about the art form.

When one looks or even thinks about Mithila art, the common image that pops in their head is of some brightly-coloured yet undeveloped art. But now, in Kathmandu, a social enterprise, Mithila House, has been established to expand this perception.

Personalising communal art

Trishna Singh Bhandari, the founder of the enterprise located in Sanepa of Lalitpur, says, “I do not mind people thinking of Mithila art as bright and loud, it is so and that is ok. But, I wish to make them aware that the art form is so much more than that, and it is beautiful and rich, in every aspect.”

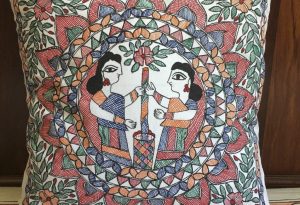

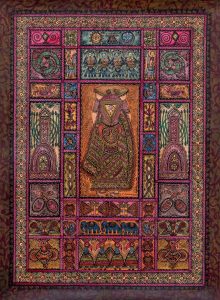

“There are two major approaches that we can see: one is the art form that we see in our Terai regions, commonly called Mithila art, and another is Madhubani art, commonly seen in the northern parts of India,” Bhandari says, “The art form is about what we see in our surroundings; nature, animals, humans and households are its muse. On the Nepal side of this art, we see humans, culture and nature whereas the India side is influenced by nature and animals.”

With her enterprise, Bhandari now wants people to know that Mithila art can be about an individual as well. “The art form has different elements, all animals or symbols have their separate meanings which were assigned during its development over the years,” she says, “Using these elements means communicating one’s feelings and of their surroundings. So it can be personal and communal depending on one’s motive.”

Promoting for bigger causes at the same time

Bhandari, who is also a founding member of the People’s Alliance for Nature Nepal (PAN Nepal), shares her enterprise has been using Mithila art as an expressive and informative tool to make people aware of the importance of the Nijgadh forest area that it is trying to protect from being developed into a mega airport.

“The forest is 8,045 hectares, and it houses a number of endangered species. While we are complaining about animals being extinct, the government is giving us an explanation that Nijgadh is an important international airport and that the animals would casually go elsewhere when they deforest Nijgadh,” Bhandari says, “To inform and make people aware, we made a series of artworks–Anautho Art–and collaborated with different artists that depicted some of the endangered species in their own way using Mithila art. This way, we can use the art form and promote a social cause.”

She also wants to revise the common understanding that Mithila art represents only the Terai region. “The art is not exclusive to any region or gender, as it is believed only women in the Terai region do it,” she says, “It is as much about the hills and the mountains and can be used to portray anything related to nature and humans. It is also possible to blend the cultural and regional aspects into one.”

As a testament to her motives, Bhandari shares that her company has made efforts to blend Mithila art with pottery in Bhaktapur, made by the local Newa community, decorated tongba (millet-based alcoholic beverage) pots that are associated with the Sherpa community, personalised copper water bottles, house decors, and clothing (including shawls, saris, bags), etc.

Now, this art form should go global, she says. “Outsiders [foreigners] have been taking our artworks as souvenirs while the locals here are still unaware.”

“I grew up surrounded by Mithila art and the lack of art today pinches me a lot. We do not want to target the tourists or expats; we want to empower Nepali women from the grassroots level; we want to minimise the market gap and accessibility of indigenous or minority communities and educate the future generations.”

Empowering women

Given the reality of the sector, women in the Terai regions are the primary artists and benefactors of the field. “Young men in the Terai have migrated for foreign employment, so we see the lack of male Mithila artists at the ground level.”

With Mithila House, Bhandari says, she is focusing on empowering women from the grassroots level. “We have women who hand-paint the products that we sell from here [Mithila House]. We act as the bridge for artists to sell and showcase their art, and better them using our training and guidance.”

Apart from two permanent young women artists working in the Kathamndu office and about 20 freelancers, the company has collaborated with a collective of 70 women in Mahottari.

“These women are involved in making natural fibre baskets and handmade silver jewellery, prominent in Tharu culture for many generations. We are giving them a market,” she says, “Likewise, in collaboration with Prithvi Foundation, we have also distributed them identity cards to boost their confidence and encourage their work.”

“To add further value to the art that we sell, we have collaborated with an initiative that makes paper from elephant dung, for art and packaging,” she informs, adding that recently, the Mithila House is also partnering with another initiative that produces banana fibres to make bags, mats, jackets, etc.