When a 54-year-old man got admitted to the National Cancer Centre Hospital in Kashiwa of Japan and got diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer a few years ago, the doctors thought it would be another miserable death within next few months. They had not known any pancreatic cancer patient living more than six months of diagnosis.

Hopeless, the patient decided to enroll in a clinical trial study in the same hospital, where the doctors applied a new medicine to him as they were experimenting its effectiveness. Three months after the beginning of the treatment, the tumour which had spread into the liver started shrinking. It ensured that he would live longer than expected.

While the patient was happy, the doctors were amazed to conclude that the new drug, arctigenin, proved effective. Equally happy was Suresh Awale, a Nepali academician currently living in Toyoma of Japan. Arctigenin was his team’s discovery.

For nearly two decades now, Awale has been leading a pioneer team of international chemists that has been making new discoveries in the field of cancer treatment.

The discovery of hope

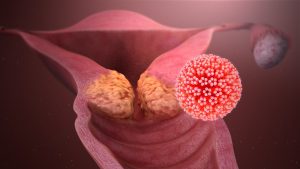

Few days back, Awale was on the news across the world again for his team’s finding that an alkaloid found in a Congolese plant can inhibit the growth of pancreatic cancer cells that could otherwise survive and expand even in the nominal presence of nutrients and oxygen.

International medical journals have commented that the discovery would provide a ‘dramatic’ and ‘promising’ development in the field of cancer treatment. Awale believes that the new knowledge deserves such attributes.

“So far, the world does not have any medicine that can fully cure pancreatic cancer. It remains one of the deadliest cancer forms as just around three per cent patients have survived more than five years,” he explains, “The rate is almost constant since the 1970s. In most of the cases, the patients live only around three to six months.”

“The global medical community was hopeless about the disease,” a smiling Awale says, “until we made the discovery a few weeks back.”

Awale is currently working as the Principal Investigator and Associate Professor at the National Drug Discovery Laboratory, Institute of Natural Medicine in the University of Toyama. The recent research was his collaboration with German professor Gerhard Bringmann. They had centred their study on a plant named Ancistrocladus likoko found in rainforests of Congo. The new medicinal compound has been named ‘ancistrolikokin E3’ for now.

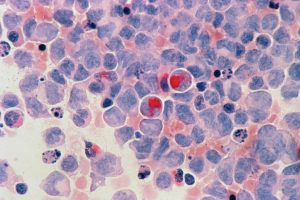

The researchers have claimed that the compound is strong enough to fight against the ‘austerity’ of pancreatic cancer cells. By ‘austerity’, they mean the quality of being alive and active for a longer time period in the nominal presence of nutrients.

“These cells are strange,” Awale explains, “Whereas cancer cells, in general, die if they are deprived of nutrients for 24 hours, these cells can survive for as long as three days.”

Now, the recent finding will be competent enough to battle the austerity as the research continues, they hope.

Building on own findings

In fact, the austerity of pancreatic cancer cells was also discovered by Awale’s team in the early 2000s.

In the following years, the team invested its energy and time in searching for remedies for austere cancer cells. The discovery of ‘arctigenin’ in 2003 was a milestone in this journey. It was a chemical found in a particular plant species easily available in Asian countries like China and Japan.

Hospitals in Japan began applying the medicine to their patients in 2010, and its results, as described by them, was a miracle.

Nevertheless, there was a problem in its application; it was unable to fight austerity in itself. While the medicine would continue its fight against the deadly cells, the cells’ death would not be guaranteed. Neither could this chemical completely stop the migration, and consequent expansion, of the cells. “It would only slow down the process, resulting in slightly longer survival of the patients.”

“But still, it was a significant achievement in the field of cancer treatment that we were successful in adding few months to the patients’ life,” Awale explains, “The application of arctigenin, therefore, made people hopeful about more exciting possibilities.”

Consequently, Awale and his team continued their quest for better medicines. They kept on experimenting different plants found in various parts of the world.

The recent finding is the latest result of the continuing pursuit of Awale and his team.

The researchers are aware that their finding will not have immediate impacts on the patients. “It will take around five years for a scientific discovery to transform into the medicine available to patients,” Awale explains, “The governments and pharmaceutical industries should take the initiative.”

He informs the researchers are in conversation with their governments in order to develop new medicines based on their discovery. “Governments of Japan and Germany own this research because we are based in these countries, therefore it is likely that the medicinal use of this chemical will begin from one between them.”

What about Nepal?

While leading international research projects in the field of natural medicine, Awale frequently remembers the roots that his grandparents used to collect from nearby forests and make him consume when he was unwell in the early childhood.

“They never game me cetamol or any other tablet when I had a headache or fever; all I had was traditional medicines, collected from forests and prepared at home,” a nostalgic Awale says, “Perhaps, this is the reason why I devoted my entire life to the search of traditional medicines in the service of the humanity.”

Awale has a wish that he would come back to Nepal someday and spend the rest of his life in the research of traditional medicines. “I believe that Nepal is richer than Japan or Germany or Congo in this field, thanks to the diverse altitude and climate we have. Our potential is beyond what we know today.”

Therefore, he wonders, “What would be more fun than doing what you enjoy doing, at your own home?”

The scientist, however, laments the lack of conducive environment for such research works in Nepal. “Whatever happening in Nepal are all the initiatives of few professors of the Tribhuvan University and other institutions,” he states, “There has not been any institutional effort.”

Nevertheless, Awale says he will continue collaborating with available Nepali researchers in order to study the plants found in the country.

Besides that, “I have been visiting Nepal almost every year” is perhaps the best thing that he can say about his love for the home country for now.

Images: Courtesy Suresh Awale