Infertility—once whispered about behind closed doors—is now coming to the forefront as more Nepali couples struggle to conceive and seek help. Defined as the inability to conceive after 12 months of regular unprotected sex, infertility affects both men and women equally, yet the topic remains shrouded in stigma and misinformation.

With changing lifestyles, late marriages, increased stress, environmental pollutants, and rising cases of untreated infections, infertility is becoming more prevalent in Nepal. According to estimates from fertility clinics, about 10–15% of Nepali couples face difficulties in conceiving, though the real number may be higher due to underreporting and social taboos.

Causes of Infertility

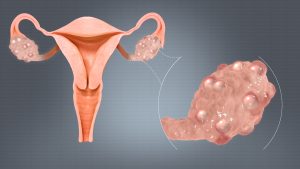

Infertility can affect both men and women and may arise from a variety of causes. In women, common factors include ovulation disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or hormonal imbalances that prevent the release of eggs.

Blocked fallopian tubes, often resulting from pelvic inflammatory disease or infections like tuberculosis, can also hinder conception. Endometriosis, where uterine tissue grows outside the uterus, is another major cause. Age plays a significant role, with fertility declining sharply after 35.

Additionally, lifestyle factors like smoking, obesity, and chronic stress can negatively impact reproductive health. In men, infertility is often due to low sperm count or poor sperm motility, which may be caused by infections, varicoceles (enlarged veins in the scrotum), or hormonal issues.

Genetic conditions, such as chromosomal abnormalities, can also impair fertility. Moreover, lifestyle and environmental influences—such as smoking, alcohol consumption, exposure to toxins, wearing tight clothing, and stress—along with infections like mumps, STIs, or untreated urinary tract infections, can significantly affect sperm health and overall fertility.

Diagnosis: When to seek help

Couples should consider seeking medical advice if they have been trying to conceive for over a year without success, or after six months if the woman is over 35.

It is also important to consult a doctor if there are known medical conditions such as irregular menstrual cycles, a history of pelvic or testicular surgeries, or noticeable signs of hormonal imbalances—such as excessive facial hair in women or erectile difficulties in men.

The diagnostic process typically includes hormone tests, ultrasound scans, semen analysis, and specialised procedures like Hysterosalpingography (HSG) to assess the condition of the fallopian tubes, and laparoscopy, a minimally invasive surgery used to examine internal reproductive organs. Early diagnosis can help guide timely and effective treatment options.

Available Treatments in Nepal

Thanks to significant advancements in reproductive medicine, a wide range of fertility treatments are now available in Nepal. These include simple lifestyle changes such as weight loss, quitting smoking, and managing stress, which can sometimes help restore fertility naturally.

Medication options, including hormone therapies and ovulation-inducing drugs like Clomiphene Citrate, are also commonly used. Surgical interventions are available to address physical issues such as fibroids, blocked fallopian tubes, or varicoceles.

Additionally, Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) have become increasingly accessible, including procedures like Intrauterine Insemination (IUI), where sperm is directly inserted into the uterus; In Vitro Fertilization (IVF), where eggs are fertilized in a lab and implanted into the uterus; and Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI), in which a single sperm is injected directly into an egg—especially beneficial in cases of severe male infertility.

For couples facing untreatable infertility, donor options such as egg, sperm, or embryo donation are also available, offering new hope for starting a family.

Breaking the silence

One of the biggest barriers to treatment in Nepal is not the lack of medical facilities, but social stigma. Infertility is often seen as a woman’s fault, leading to emotional distress, blame, and even domestic violence in extreme cases.

It is time we talk openly about infertility, recognise it as a medical condition, and support couples in their journey. Both men and women deserve access to accurate information, compassionate care, and a society that understands their struggles without judgment.

Infertility is not the end of the road—it is a medical challenge with real solutions. With growing awareness, better diagnostics, and expanding access to treatment, there is hope for countless Nepali couples dreaming of parenthood.