Provincial governments in Nepal are changing one after another.

Bagmati Chief Minister Shalik Ram Jamkattel received a vote of confidence on March 24 after the CPN-UML withdrew its support extended to him. For international observers, this might sound strange as the UML proposed him for the chief minister just two and a half months ago. But, for Nepalis, this is just a regular affair as the country’s provincial governments have not been able to function autonomously so far.

Accordingly, chief ministers of Gandaki and Lumbini–Khaga Raj Adhikari and Leela Giri–are going through the same fate in the next few weeks. The CPN-UML leaders’ chief ministership is at stake with the Maoist Centre not supporting them.

Whenever political equations change at the federal level, the most immediate authorities to receive the shockwaves are provincial governments. Hence, as soon as the CPN-Maoist Centre broke away from the CPN-UML coalition in the run-up to the presidential election last month, most provincial governments–formed by the constituents of the federal-level ruling coalition–were certain to receive hits.

Observers and stakeholders say this practice has jeopardised the spirit of federalism that the 2015 constitution envisioned, giving birth–albeit on paper–to the autonomously functioning legislative and executive bodies at the provincial level.

Autonomy snatched away

On March 5, Sudurpaschim province chief Kamal Bahadur Shah received a vote of confidence to ensure that his government formed last month will last longer. Among the major parties to trust him was the Maoist Centre.

But until a few hours before that, the Maoist party was adamant that it would not support the Nepali Congress leader unless there was a written agreement on power sharing. But soon they were helpless to submit themselves to the party’s central chairperson Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s directive.

In fact, they were in a position to vote for Shah only after the written agreement. But later, following the command of the central committee of the CPN Maoist Centre, the parliamentarian of the CPN Maoist Centre of Sudurpaschim, agreeing on an oral agreement, gave a vote of confidence to Shah.

“Following the instruction of the central committee, we gave a vote of confidence to Shah,” said Khag Raj Bhatta, the parliamentary party leader of the CPN-Maoist Centre. “The power-sharing among the alliance will also be determined according to the agreement held at the central level.”

Reportedly, the provincial assembly members who came to Kathmandu for the presidential and vice presidential elections earlier this month were simultaneously busy lobbying with their parties’ central leadership to nominate them for chief ministers and ministers. It is apparent that it is the federal leaders, not the provincial lawmakers, who make the governments.

Against the constitution

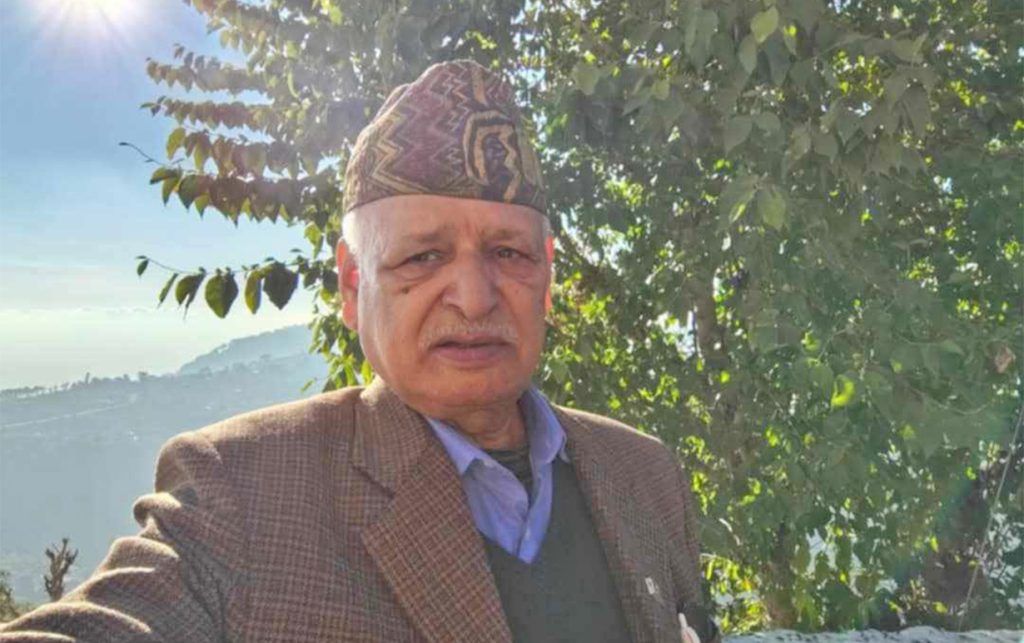

Political analyst Jagat Nepal says this practice is against the spirit of federalism as per the constitution.

“In federalism, the provincial government is supposed to be autonomous. But in Nepal, things are different, ” Nepal says, “Here, the structure of the central government determines the structure of the provincial governments.”

Nepal says the central leadership should be held responsible for this trend more than the provincial leaders. “Those in the central committee are reluctant to grant autonomy to their provincial bodies and provincial governments in order to maintain their grip.”

Rudra Sharma, a federalism expert, also says that the concept of federalism is wrongly being practised in the country.

“Federalism is just a political concept here in Nepal; it hasn’t been a part of the administration and economics of the country,” says Sharma. “Due to that, our leaders are failing to understand its spirit.”

The inability to prepare the Staff Adjustment Bill to date also shows that federalism has not been a part of the nation’s administration, he says, adding there is no way provincial governments can function autonomously anytime soon.

Both Nepal and Sharma believe that once federalism becomes a part of the administration and economy, not only politics, expected changes can be seen in the country. “But it is certain to take a long time here in Nepal,” says Nepal.

Sharma says there are certain areas–such as national security and foreign affairs–in which federal governments can control the autonomy of provincial governments. “But the way Nepal’s central power is ruling the provinces–to control each and every movement–is inappropriate.”