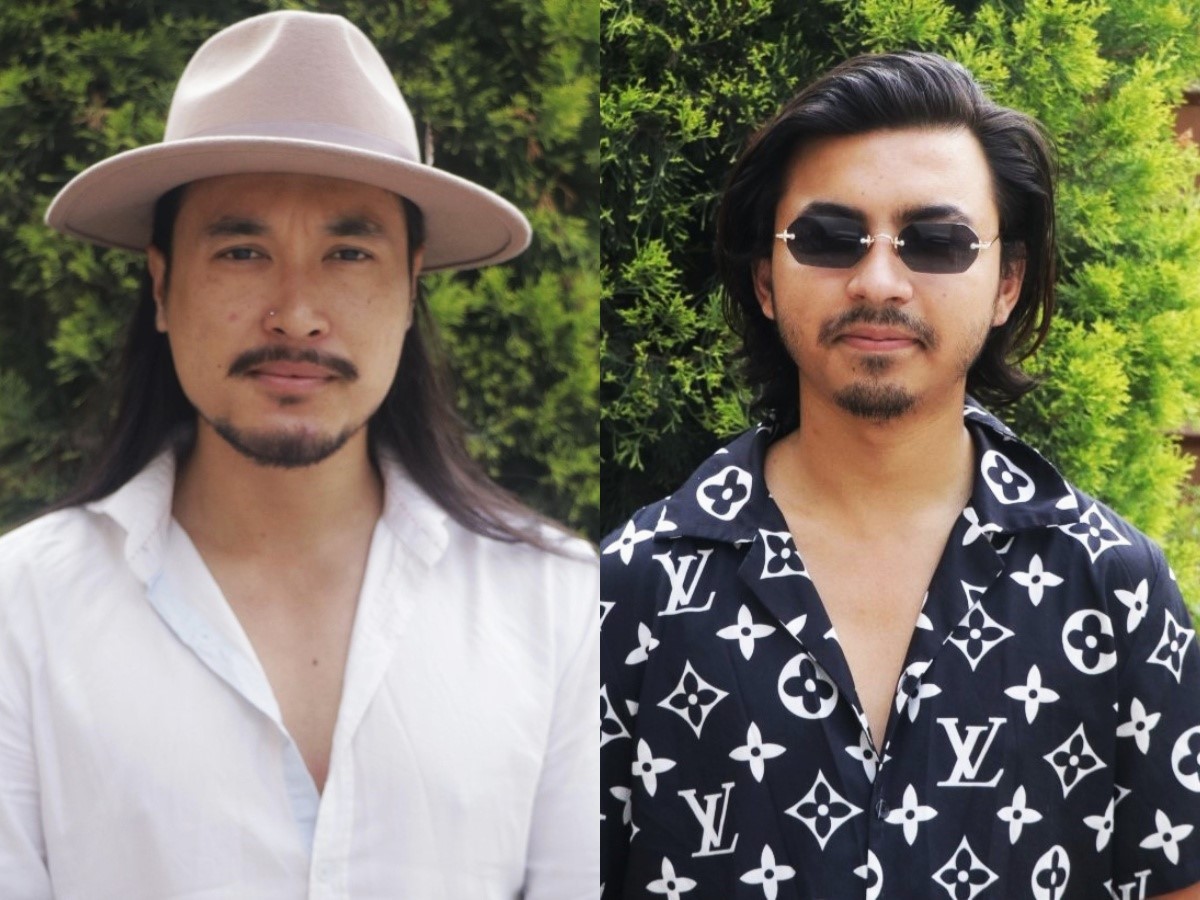

Hira Bijuli Nepali returned to his hometown of Mugu after studying acting in Kathmandu 10 years ago. He went back home with an aim of establishing a space to conserve the art and culture of the Karnali region. For that, he established Karnali Arts Centre, which also became one of the pioneering theatres outside Kathmandu.

It did not take him long to realise that running a theatre, that too in the remote district of Mugu, was not a cakewalk. “Challenges came in one after another,” he said in an interaction during the Nepal International Theatre Festival in Kathmandu recently, “Many times we tend to think theatres outside Kathmandu don’t have any reason to survive.”

“Yet, we are surviving as we are struggling,” he said.

Other artists operating theatres outside Kathmandu agree with him as they say they continue their struggle because they believe they are also offering a ray of hope to the country’s theatrical community.

Challenges galore

Nepali is known in Kathmandu’s theatrical scene since 2008 when he acted in the play titled Karnali Dakkhin Bagdo Chha (Karnali Flows Southwards) at Gurukul Theatre, the most celebrated theatre in the capital then. The drama that exposed the hardship of the people in Karnali received much appreciation from the audience in Kathmandu, which made him realise the power and importance of the culture practised in the Karnali region.

That motivated him to open the Karnali Arts Centre, but the challenges he faced made him doubt his decision many times.

“Unlike the capital’s theatres, we [theatres outside Kathmandu] do not have the access to resources from government bodies, NGOs and INGOs who would help us to enhance our status,” says Nepali.

The theatres around the capital city are proliferating, garnering a good audience and are financially strong, but the theatres outside Kathmandu have remained distant from such progress.

Kalalaya Itahari, a theatre in Sunsari, for example, does not have its own hall to perform. “We need to practise and perform in the rented hall, which is one of our biggest challenges,” says Sonu Jayanti, the director of Kalalaya Itahari.

Similarly, brain drain is also another challenge for the theatres outside Kathmandu. Jayanti says, “It takes at least two years to make the actor or technician skilled, but later they leave the theatre to go abroad either for study or employment.”

Getting inspired by other theatre groups, Suresh Sapkota and his team opened a theatre in Butwal just before the Covid pandemic.

But, the pandemic halted all their operations. Meanwhile, in Butwal, except for resources and financial factors, Sapkota also takes the hot weather as another challenge, claiming it makes the audience reluctant to watch a play.

A ray of hope

Similar to his peers, Pari Wartan from Pokhara Theatre also has stories of lack and loss. Yet, he says he is determined to continue the struggle.

In the past five years since its inception, Pokhara Theatre has staged over 60 plays and organised an international theatre festival, the director says, “But, only a few people know about it, yet we are committed to promoting our stories. And, consequently, I have seen the popularity of theatres outside Kathmandu growing of late.”

Currently, there are 12 full-time actors at Pokhara Theatre, but he complains it is not sufficient to stage the plays on a regular basis.

Nevertheless, the theatre has made the effort for its sustainability. It has been regularly organising a school theatre festival, whose fourth edition was completed recently.

Likewise, Kalalaya Itahari also frequently organises workshops for school students and interested individuals to survive.

Karnali Arts Centre is managing its finance differently for its sustainability. “We have some well-wishers who understand our ideas and goals and help us to sustain,” says Nepali. “Sometimes, we also do work for various agencies.”

Nepali is planning to establish another theatre in Surkhet because he says it is the power centre of the Karnali province. “Things are relatively accessible in Surkhet and our movement to enhance the voice of minorities can also be impactful there,” he says.

Call for support

Meanwhile, it makes him feel bad to see the Kathmandu-based actors going to remote areas, including Karnali, to perform drama. “There are many local talented actors from far-flung areas who have contributed their entire life to acting, but their works are not being recognised by the concerned bodies,” says Nepali.

According to him, politics within theatres in Kathmandu is bigger than mainstream politics.

While Nepali expects Kathmandu-based theatres to support theatres outside Kathmandu by promoting local artists and stories, Sapkota believes they should take their own initiatives.

“They should focus on original plays rather than remaking the plays staged in Kathmandu to uplift their current status,” he says.

Yet, he expects a healthy collaboration between theatres outside Kathmandu and those based in the capital. “It’d be great if Kathmandu’s theatres tried to feature the actors from outside the valley in their plays.”