If you love Elvis Presley’s ‘Love me Tender’, you would have loved to see this play set in the late 30s. Golden Boy, which revolved around the story of a 12-year-old Joe Bonaparte (Amrit Dahal), an aspiring violinist caught between his love for art and the lucrative, yet dark, world of boxing. His affinity towards violin comes from his father, Mr Bonaparte (Rajkumar Pudasaini), an Italian who literally lives with music (operas), profusely speaking of his love for the trees and streams and cities and everything that has ever walked the earth.

However, pursuing music for Joe, as explained in the play, does not make ends meet for the Bonaparte family as it recently moved to the USA. So the 21-year old Joe resorts to making a living by boxing.

Act I begins with three characters under the spotlight, an ambitious boxing manager, Tom Moody (Alejandro Merola), his mistress and more precisely a perfumed vanity, Lorna Moon (Namrataa Shrestha) and the protagonist- ‘Golden Boy’, Joe Bonaparte (Amrit Dahal).

Enclosed inside a boxing ring, Dahal delivers a fiery dialogue but all you can imagine is a whiny schoolkid complaining to his father. Somehow, Dahal’s modulation of voice and delivery of speech is far from the wrath of a lonely boy with a confined career option.

Merola surprises the audience with a seamless performance and the dexterity through which he propels the play is commendable. His words come out like a stone freed from between the catapult-smooth and the trajectory reaches the high summits of humour and satire, all of which amounts to an articulate performance. He apparently knows when to pause, react or be taken aback.

Namrataa Shrestha, a well-known Nepali actress conjures up a splendid show inheriting certain poise and nuances of a New York-based lady and lover. There is something charming about her even in the smallest acts of holding a cigarette between her fingers and drawing the smoke in or heaving it out. That’s the kind of lady she is supposed to portray and she enacts it with confidence and ardour.

Right before the interval, Dahal performs a poignant, yet beautiful, ballad where at one time his hands are playing the violin and drawing away just after, metaphorically hinting at the his dilemma. The swaying motion of the violin suggests that his heart is content with the current lifestyle of tranquility with music being his only companion. Then, the sudden stifled hands drawing away suggests the contradiction of the mind that craves for the flashy cars and popularity. The solo act under the spotlight is the most mesmerising part during the first act. The question remains suspended whether Dahal will listen to his heart or brain.

The filler of the interval between the two acts is a live boxing match by members of the Naxal Boxing Club, who entertain the audience. Post some peanut and cola, everyone is seated and the drama resumes.

It is then that Roxy Gottlieb (Bikash Gurung) is introduced as the manager of the boxing team. A cheeky old man whose bleak attempt to keep the humour intact with satirical lines goes in vain as it fails to gather uproar from the audience.

It is unfortunate that most actors miss the punch lines in a hurry to blurt out the dialogue and conversations which could have left the hall in an echo of laughter cannot yield more than a few chuckles.

In fact, Joe’s brother-in-law, Siggie (Hemanta Chalise) is a lovable character in his staple suspenders whose actions are often governed by whims. He successfully has the audience laugh a little with his peculiar accent.

The play takes a turn when Dahal bags every match and becomes a champion in no time, earning the title ‘Golden Boy’. Needless to say, he is followed by many women who charm him and stunt his performance. Consequently, his managers, having to bear the brunt of his polygamy, ask his mistress, played by Shrestha, to spend more time with him so that he remains away from other women. In the course of time, there persists a romance between the two and the play takes a new turn.

“When a bullet passes through air, it has no past. Like me.” The dialogues of a rebellious man, Dahal, gushing out vented emotions through fierce boxing as a way of feinting with the predicament comes off wry.

The dialogues are fantastic. But the credit goes directly to the writer of the play, not the cast enacting them. “Right here there’s a hard lump. I drink to dissolve It,” as said by Shrestha with a grimace is most captivating and believe it or not, she says with such confidence, one is compelled to ponder over it.

She delivers excellent gesticulations of a nervous, excited and tragic lady.

The play continues with the tumult of a love triangle between Dahal, Shrestha and Merola. The part where Shrestha dismisses any romantic link with Dahal is the fulcrum of the play which drives it to an unexpected end.

The play teaches one that the cost of free will is much greater than that of the silk shirts and Buicks. The ultimate idea of the play is to follow our heart and let it lead us wherever it thrives for in the end. All that matters is not the debris of wealth but the content heart.

The lights and jazz music in the background revive the old classy era of the 30s with jazz numbers like “Sing Sing Sing’’ by Benny Goodman. Deducing, the play is a fair attempt which proves that Nepali actors can do noir as darkly as the others.

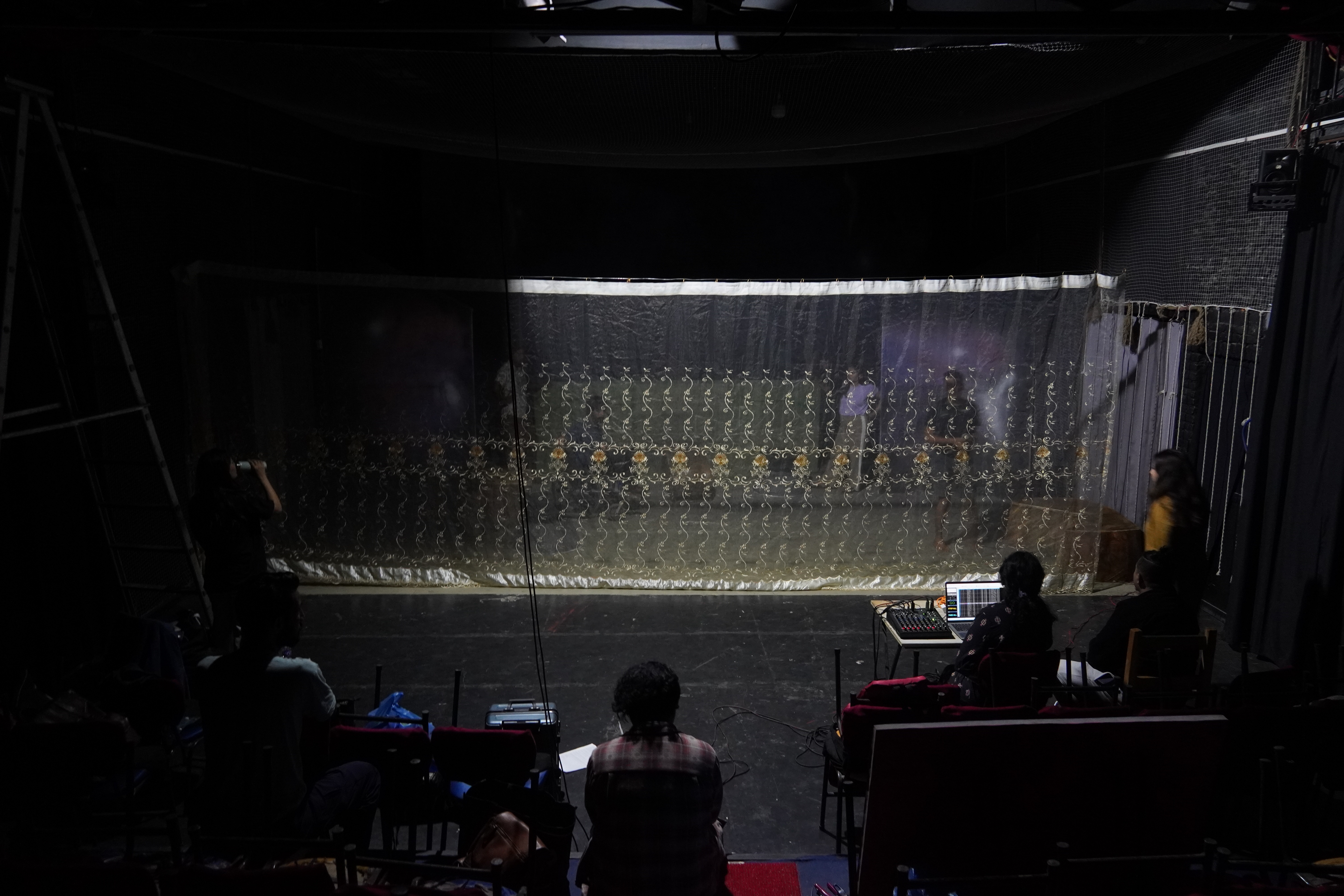

Directed by American theatre artist Deborah Merola, the play was staged at Karma Lounge and Bar in Kathmandu from September 1 to 10.