Sitting in a small room, Tej Bahadur Chitrakar paints a mask of (Halchok) Aakash Bhairav and outlines the deity’s white teeth and fangs. The 83-year-old of the Chitrakar family has been doing this work for the annual Indra Jatra since 1971 and, despite his age, he does it with complete finesse thanks to his steady hands.

“Our family got the responsibility in 1896. My forefather got the work passed down from another relative of ours, who could not continue then for some reason. But, as for how the work was first given to us, it is not clear,” says Chitrakar.

Remembering his early days, he says, “I should have been about 10 years old when the masks were brought to our home and my father [Ganesh Chitrakar] used to decorate them. That time, it was in an older house and a much smaller room. And, he would work alone and dismiss us from the room, even when we took interest. He used to take it not just as a family responsibility but a kind of devotion to the god.”

“Even until 1970, he did not involve me in the process. So I never got to learn the art from him, But, when we got paralysed, I took over the responsibility as my own, learning through mistakes with the help of my uncles,” he talks about how he continued the family legacy every Indra Jatra with the same devotion.

So, to correct that now, he is teaching and supervising his grandnephew, who has been helping him in the process for many years now. “It is only right that we pass this on to the next generation,” he says.

The making

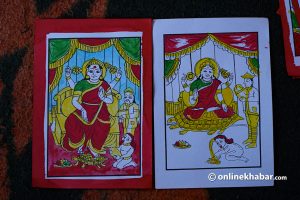

The Chitrakar family does not just decorate but they are also the ones that make the masks used in the Aakash Bhairav Naach that reaches core Kathmandu from the hills of Halchok on the valley’s western side. “The masks are made only once every 12 years. It is made up of layers of cloth, a jute sack, Nepali kagaj (paper) held together with maad (made of flour). At that time, all 10 masks are made and decorated during Chaitra (mid-March to mid-April).”

For the yearly dance, they take a week to redecorate the masks. “Members of the Shree Halchok Aakash Bhairav Guthi dropped the masks here a day after kushe aunshi [on Bhadra Shukla Dwitiya this year]. We perform a small kshama puja [ritual for forgiveness] on the day and then start working on the masks from the next day.”

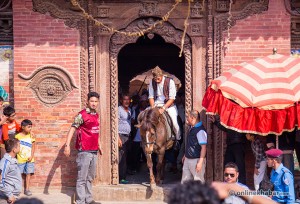

“On the following Ekadashi [Friday, September 17, this year], we perform another kshama puja–for any mistake in colouring and decorating or because our feet touch the masks–and hand them over to the Guthi that takes them back to Halchok for the Aakash Bhairav Naach we see during Indra Jatra,” explains the artist.

In 10 days, the Chitrakar family finishes preparing the masks. “We first check for any damage to the base. If the base is okay, we start with colouring the masks [blue for Aakash Bhairav, and red for Chandi Kumar and Chandi Kumari]. This is locally known as lwampuli/lapuli chhyayegu [to colour]. If the base is damaged, we fix that first and then start colouring and add the details.”

As per the customs, Chitrakar with his grandnephew, Rabikar Prasad Ghimire, starts colouring early in the morning from about 7/7:30 and continues till noon and starts again the next day. The duo fill in the details, and when all is done, they work on the eyes.

“It is like a symbol that says the god has awakened. After that, we do not touch or make changes to the masks. It is believed that one should not look directly in the eyes of the deities, or else their health will suffer. So we avoid any kind of direct eye contact and do not make any heavy changes. At last, we put a protective coat to prevent the masks from water damage and finish the work before handing them over,” explains Ghimire.

For all this, the Chitrakar family used to get only 33 paisa per mask as a payment. Other than that, the Guthi used to give them four blocks of rato maato, 21 ghoka (pieces) of maize and 10 eggs yearly for their association with the work. But, this has been discontinued and the family is working without any pay whatsoever.

Like granduncle, like grandnephew

This annual work takes the Chitrakar family busy for about 10 days around Indra Jatra. For the rest of the time, the family has kept themselves busy with other work. Because his father did not keep them involved, the veteran artist got into electrical engineering in his youth. He joined Nepal Doorsanchar Company (Nepal Telecom) in 1958.

But, even while working, to continue his family legacy, he used to take a week’s leave from the office and devote himself, alone, to the colouring of the masks for the Indra Jatra festival. After his retirement in 1993, the annual feat became much easier for him.

Yet even for the rest of the year, Chitrakar still proved to be a craftsman for many. “Being an engineer, he was quite popular among our family and friends as they would call to fix home appliances regularly. And, he enjoyed it,” shares Ghimire.

Much like his granduncle, he also is managing the family legacy and his professional work side by side. “I was in grade seven when I first got inquisitive about the tradition. He got me involved, and I started by making the dotted white lines [on Chandi Kumari’s mask].”

With the new generation of legacy, some new ideas also popped into the process. And in this, the technology proved to be a big help. “As we are recreating the design, manually, there is a high chance of error. We try our best to get the details right, but something is bound to change. Also, when we did not have a camera–we could not even afford it–it was really hard to replicate the design exactly.” Their only reference would be old, black and white photos.

But today, phone cameras and internet photos have come in handy to replicate the designs. “The focus is always to capture the emotions that one can easily relate with the fierce-yet-happy image of (Halchok) Aakash Bhairav according to the legends.”

Some changes seen today were introduced after Ghimire joined hands and he is happy about this. “It is a prevalent element of Indra Jatra that everyone sees first [in the procession]. And, this is a big part of our family, so I feel very proud to be associated with the age-old tradition. “

“We have always wanted to make it better and we have made a few changes accordingly. First, we gave proper shape to the skulls [seen in the headgear in the Aakash Bhairav’s mask] and outlined the ear like that human and teeth to make it more relatable.”

While some changes were heartily welcomed, some have gotten much criticism too. “We have had to leave behind many traditional art forms and adopt new ones, including the colours we use [from flower powders through the enamel to poster colours now] or the water-proof coating we use [wood primer to polyurethane now]. Commercialisation today has also made it harder for us to achieve the same results,” says Ghimire.

Ghimire adds, “There will always be a difference in opinions among people, be it in colour or design and even shape. But, it is the mutual understanding between us and the Guthi that makes it work.”

The time factor

Meanwhile, time has caught up with the veteran mask maker. “At 83, now, it is getting hard for me to sit cross-legged and focus on the minute details.”

“My grandnephew has been a great help. So has been my wife, Aasha Maya, who even took over the work when I was in Japan for one year [1978]. But sadly, no other relatives have taken much interest in this tradition.”

The Chitrakar family, for seven generations, have been owning and investing their time in the making of the masks. Yet it is not the family who has the say in who decorates them. “The guthi decides that every Indra Jatra,” says Chitrakar.

Ghimire, who has taken great interest and ownership of the art and family legacy, has invested a great deal in research too, yet, he is worried. “As much as I want to, if the guthi decides they do not want to continue with us, that is after my grandfather, we will have no say in that. But if I get that chance, the privilege, I will honour it to the fullest and take the legacy forward every Indra Jatra with our future generations too.”

Originally published on September 17, 2021