Tucked between the towering Himalayas, Nepal has a rich cultural heritage and spectacular natural scenery. However, underneath this lovely frontage lies a complex economic issue, a persistent trade deficit.

A country is considered to have a trade deficit, indicating an imbalance in international trade, when its imports exceed its exports. For years, Nepal has struggled with an economic barrier caused by several factors that contribute to this imbalance.

Numerous challenges brought forth by the trade imbalance affect employment, growth in general, and economic stability. For a considerable stretch of time, Nepal’s trade deficit was Rs 157.14 billion in exports compared to Rs 1.611 trillion in imports in fiscal year 2022/2023.

This makes it clear that Nepal depends entirely on imports.

Data on imports and exports

In fiscal year 2022/2023, Nepal had a staggering trade imbalance of Rs 1.454 trillion. The trade imbalance has decreased by 15.45 per cent as a result of the luxury goods restriction that took effect in April 2022 and prevented the use of foreign exchange reserves.

Controlling the trade imbalance is the primary motivation. Over that time, 21.44 per cent of exports had decreased. For the first month of fiscal year 2023/2024, the trade imbalance was Rs 115.71 billion, and every government action attempted to limit it failed. At Rs 53.769 billion, Nepal’s total imports in fiscal year 2022/2023 are almost equal to its total exports for the year.

The World Bank’s April 2023 report on Nepal Development Update states that real GDP growth dropped to an estimated 1.9 per cent in fiscal year 2023, the slowest pace since fiscal year 2020, which is 10 years below the average growth rate.

While the industrial sectors of Nepal’s economy are experiencing a downturn, the agricultural sector remains robust. Imports of goods were sharply reduced as a result of domestic regulations and trade restrictions imposed by India.

In order to facilitate the repair of external imbalances and reduce the growth rate of lending to the private sector, Nepal Rastra Bank increased its policy rate early in the fiscal year 2023. Compared to fiscal year 2022, the private sector seems to be smaller.

Since commerce accounts for more than half of overall income, the import rate precipitously reduced those revenues. The fiscal deficit almost doubled to 6.1 per cent of GDP, the largest level in more than 20 years, as spending shrank much more slowly than income.

The World Bank’s growth estimate increased to 3.9 per cent in fiscal year 2024 and 5 per cent in fiscal year 2025, with the benefit of removing import restrictions and gradually relaxing monetary policy helping to offset the lag.

The industrial sector seems to be producing more hydroelectricity, and the growth rate of imports is anticipated to assist wholesale and retail commerce. However, the drop in rice and paddy output in fiscal year 23/24 and the dumping of diseases on cattle seem to be slowing down the agricultural sectors.

The import limits imply a rise in goods imports over the medium term in terms of monetary policy. The current account deficit is predicted to increase to 3.7 per cent of GDP in fiscal year 24 and 4.6 per cent of GDP in fiscal year 2025. Taxation places a strong emphasis on commerce, and revenues are predicted to rise in tandem with the import of products.

According to the Asian Development Bank’s September 2023 macroeconomic bulletin, Volume 11, No. 1, the market price of the Nepali economy is expected to expand by 4.3 per cent in the fiscal year 2023/24 compared to an anticipated 1.9 per cent growth in the fiscal year 2022/23.

According to the research, average inflation on Indian oil imports is expected to drop from 7.7 per cent in fiscal year 2022/23 to 6.2 per cent in fiscal year 2023/24. Remittance inflows have been increasing by 4.38 per cent and reached Rs 1.22 trillion in the year fiscal year 2022/2023.

Central Bank monetary policy and trade deficit correlation

According to NRB fiscal year 2023/24, the agency’s projected fixed rate is 6.5 per cent. The account deficit decreased from 12.08 per cent to 12.03 per cent as a result of a significant remittance flow and a decrease in imports. Foreign reserve accumulation rises by USD 9.5 billion in July 2022 and USD 10.1 billion in mid-June 2023.

The cash reserve ratio (CRR) and the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) have increased. The percentage of deposits that banks must invest in government securities is known as the SLR, while the percentage of deposits that banks must keep with the NRB is known as the CRR.

The NRB also provides a number of incentives to promote exports. The NRB, for example, has introduced a brand-new exporter refinancing scheme where exporters may apply for loans at a reduced interest rate.

Measures to control trade deficit in Nepal

The best way to do this is by offering exporters financial incentives like tax exemptions and subsidies. To increase exporters’ competitiveness and open up new markets, the government may also assist them. When feasible, replace imported items with native ones to help Nepal lower its import bill.

This may be achieved by encouraging the growth of sectors like manufacturing and food processing that can replace imports. To consumers and companies, the government may also put tariffs or other limitations on imported products.

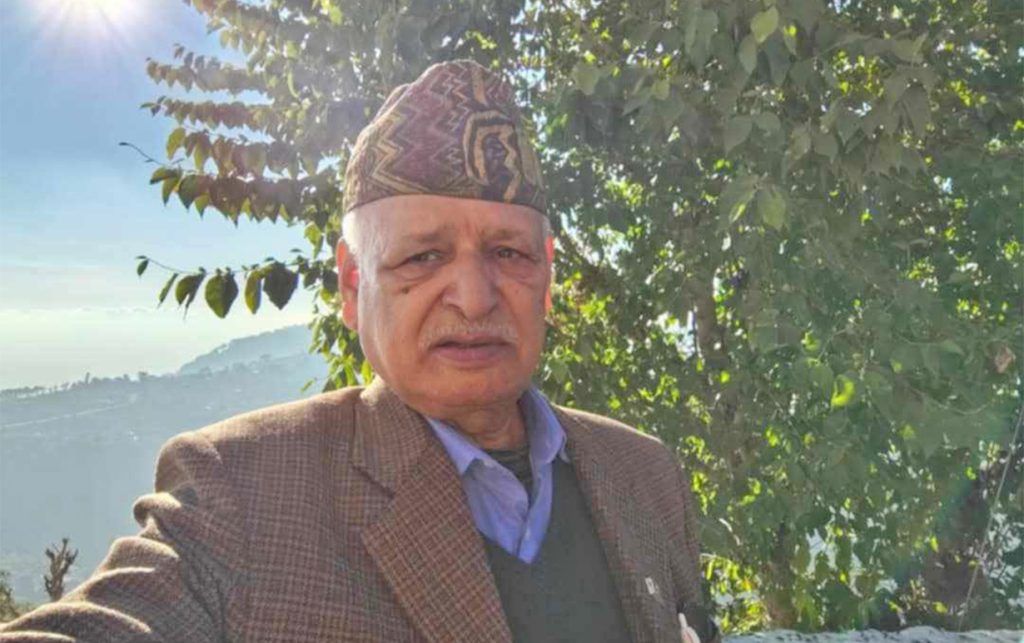

However, this should be done wisely. By establishing stronger trade agreements with its trading partners, reducing tariffs and other trade restrictions would be necessary for this. In a speech on September 22, 2023, Dr Maha Prasad Adhikari, the Governor of Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), listed some of the most important steps that may be made to reduce Nepal’s trade deficit.

Nepal should prioritise growing and advancing its export-oriented sectors, including tourism, hydropower, and agriculture. To increase its access to markets, Nepal may potentially join regional trade blocs like the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA).

It is challenging for companies to operate and transact in Nepal due to the inconvenient bureaucratic processes. The government must cut red tape and simplify its processes. Improved education and skill levels are necessary for Nepal’s labour force to remain competitive in the international market. Programs for training and education must be funded by the government. Nepal must make its surroundings more attractive to international businesses