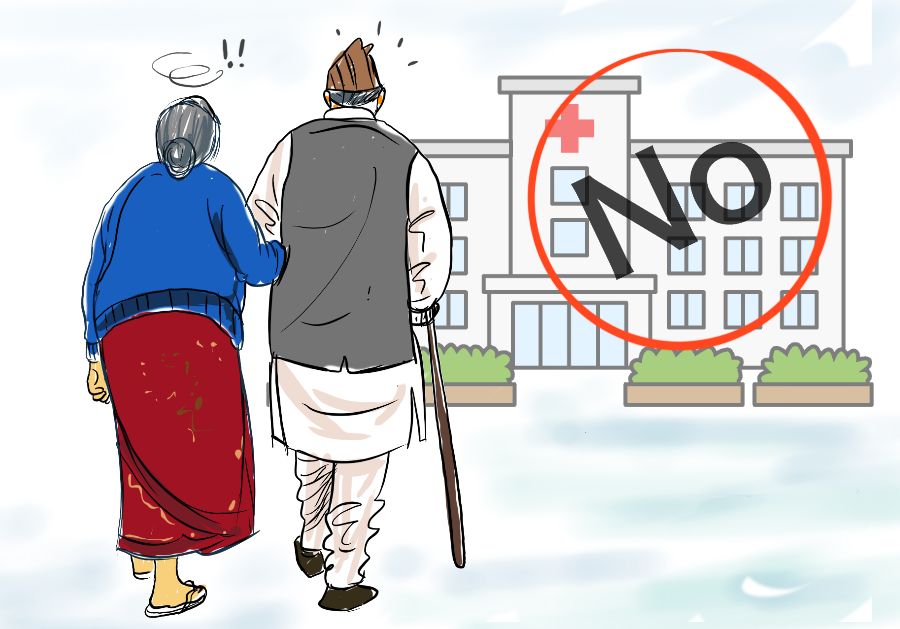

The doctors throughout Nepal are protesting. As they have taken to the streets, healthcare facilities across the nation are currently in chaos. The outpatient departments (OPDs) in a few hospitals over the course of the past few weeks have been temporarily closed due to the protests by these doctors, who have been demanding workplace safety since September 26.

A year ago, the first amendment to the Security of the Health Workers and Health Organisations Act (2010) was enacted to address the demands of healthcare workers regarding workplace safety. On the day it was enacted, health workers even celebrated it, believing that the amendment would guarantee workplace safety. They also held the belief that those responsible for incidents involving assault or misconduct on health workers would be punished. However, this belief proved to be short-lived.

Incidents of physical assault or misconduct continued to occur in cases related to patient treatment or death. In the past two weeks alone, 10 doctors were assaulted or subjected to abuse. People, dissatisfied with the treatment or perceived negligence of healthcare workers or doctors—who are often revered as lifesavers—resorted to expressing their anger through acts of violence.

According to doctors, there has been a growing gap between them and the people, and this cannot be attributed to a single factor, as there are numerous factors at play. However, one of these factors has been the people’s disappointment.

Stuck in time

Even after eight years since Nepal adopted its new constitution, the country has struggled to maintain consistent political stability. This ongoing instability has eroded public trust, leading to an increase in social disorder. Unfortunately, during times of escalated chaos, doctors and healthcare facilities have frequently become targets as well.

Dr Jagdish Agarwal, the former dean of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), emphasises that a deficiency in communication or counselling between the patient, their relatives, and the doctor concerning the treatment process can breed distrust and suspicion towards healthcare workers.

“Simultaneously, incidents such as assaults and abuse of healthcare workers occur,” he says.

Dr Bhagawan Koirala, the president of the Nepal Medical Council (NMC) and a senior cardiologist, says that patients and their families are in search of compassion from healthcare workers. They want to witness genuine efforts during treatment. However, on occasion, due to various factors like managerial errors, staff shortages, or the inherent limitations of healthcare workers, achieving these ideals has proven challenging.

“It is wrong for the patient’s relatives to vandalise the institutions and abuse doctors because they don’t get justice in time,” says Koirala. “But the government agencies that were set up for justice are also guilty.”

In most cases of medical negligence, both mechanical and human errors are evident.

“The council cannot take action in cases of negligence. Even to pursue legal action, one must follow the council’s procedures,” says Dr Harihar Wasti, former coordinator of the Ethical Review Board. “Our legal process is often unable to deliver timely justice to the real victims.”

Former president of Nepal Medical Association, Dr Lochan Karki says misleading and incomplete information also widens the gap between healthcare workers and citizens.

Poor system

While healthcare workers are often referred to as gods, it is crucial to remember that they are, in fact, human beings. Even with the best of intentions, human errors are unavoidable. If someone believes there has been medical negligence or that a patient has died as a result of it, there should be a system in place to lodge complaints within the hospital.

Health institutions that adhere to the practice of good healthcare typically have an ethics board responsible for addressing such concerns. In cases of misdemeanours, negligence, or patient deaths, there is a protocol for establishing an investigative committee within the healthcare institution. The final report should be provided to the patient or their relatives following the investigation. Unfortunately, this practice is not observed in healthcare institutions in Nepal.

The primary channel for seeking justice is through the Nepal Medical Council (NMC). Founded in 1963, this council scrutinises complaints regarding treatment lapses and administers appropriate actions against doctors who are deemed guilty.

However, the NMC has struggled to earn the trust of people. This is primarily attributed to the process of appointing the chairman of the council. Typically, a political party or coalition in power selects their preferred candidate for this role, with some exceptions. Despite the rule that members, including the vice president, should be elected, political party-affiliated institutions continue to wield significant influence in the appointment process.

Lately, members of the council have been seen advocating exclusively for doctors, according to the former registrar of the council, Dr Shree Krishna Giri.

“People feel that their concerns are not being heard, leading to a lack of trust in the council among the general public,” says Giri.

There are further concerns regarding the council’s approach to taking action. When a complaint is filed, the council often takes months to conduct an investigation, ultimately resulting in a decision to issue a warning or bring attention to the matter. According to former members, such outcomes are frequent due to a failure to fully exercise their rights within the council.

If medical error or negligence is proven, the council holds the authority to issue a warning or suspend the doctor’s license for a period ranging from one month to two years, depending on the severity and nature of the incident.

However, the reality is different and incomprehensible within the council, says Wasti.

Legal remedies can also be sought under the Consumer Protection Act and the National Criminal Procedure. However, this process must be pursued through the NMC. The bureaucratic hurdles within the council have led many individuals to lose faith. Wasti believes that if confidence in this process can be established, incidents of violence might likely decrease.

Weak regulations

The Health Workers and Health Organisations Act (2010) stipulates that in the case of vandalism within a health institution or physical assault on health workers and employees, the offender may face imprisonment for up to three years, a fine of up to Rs 300,000, or both.

Similarly, if a health worker or an employee within a health institution is found guilty of assault, making threats, or exhibiting abusive or disrespectful behaviour, they may be subject to imprisonment for a maximum of one year, a fine of up to Rs 100,000, or both.

In such cases, there is a provision that allows the investigating officer to detain the accused for preliminary investigation if there is reasonable cause to believe that the individual is involved or suspected based on immediate evidence.

However, the implementation or enforcement of the Act is very weak.

“The primary responsibility for enforcing the law lies with the local administration. Yet, in every instance, there is a need for the health workers to protest out in the streets to seek justice,” says Dr Shree Krishna Giri, former registrar of NMC.

Dr Lochan Karki says, in most cases, the fear of mob pressure deters people from pursuing legal proceedings, leading them to opt for unofficial settlements.

“A mob appears suddenly in the hospital. If there is vandalism, there will be a loss of property worth millions. Moreover, even if hospitals don’t have any fault, they have the mentality to settle the case unofficially by paying Rs 1 to 1.5 million,” says Karki.

“If they were to be penalised for such vandalism, hospitals would not settle either. So, those who provoke and incite the relatives of the sick or deceased should be curtailed.”

All of these factors contribute to people lacking confidence in receiving justice during such incidents, and healthcare workers also do not feel secure in their workplace. Koirala says that incorrect narratives, such as the belief that treatments are superior in foreign countries compared to Nepal, and the notion that some doctors are primarily driven by financial gain, have further fueled negative perspectives towards medical personnel.

Doctors also acknowledge the trust gap. A senior doctor expresses concern as he says they are compelled to stage strikes.

“In pursuit of justice, doctors sometimes resort to sudden strikes, resulting in the deprivation of treatment for many people, and in some tragic cases, the loss of lives.” Doctors acknowledge that such actions contribute to a growing divide between doctors and citizens.

This story was translated from the original Nepali version and edited for clarity and length.