Following the spike in infections and death rates, the governments in nearly 200 countries across the globe announced full or partial lockdown and started closing educational institutions in March 2020 in order to contain the spread of the coronavirus. With educational institutions including schools physically shut down, academic activities were shifted to the distance mode of teaching and learning. Despite concerted efforts made by educational institutions to keep the learning activities intact during this period, teachers and students were compelled either to rely on limited resources such as the internet-mediated platforms for interaction, television and radio or remain unreached by all of these means.

Hardly had schools been back in place after the gradual lift of prolonged lockdown in many countries when the second wave of the pandemic brought a more deepening crisis to the fore. It has adversely impacted all the educators, teachers, parents, students and alike regardless of their geographical locations, socio-economic privilege, educational backgrounds, and gender differences across societies. But, when it comes to the scale of impacts the pandemic has had on them, the same is not true for all. In Nepal, the education system in public schools was already in shambles due to performance and capacity crisis even before the pandemic. But, back to back closures further laid bare the widening gulf between haves and have-nots across communities, requiring stakeholders including the government to deal with this newer problem in a stronger way.

Ever widening educational equity gaps

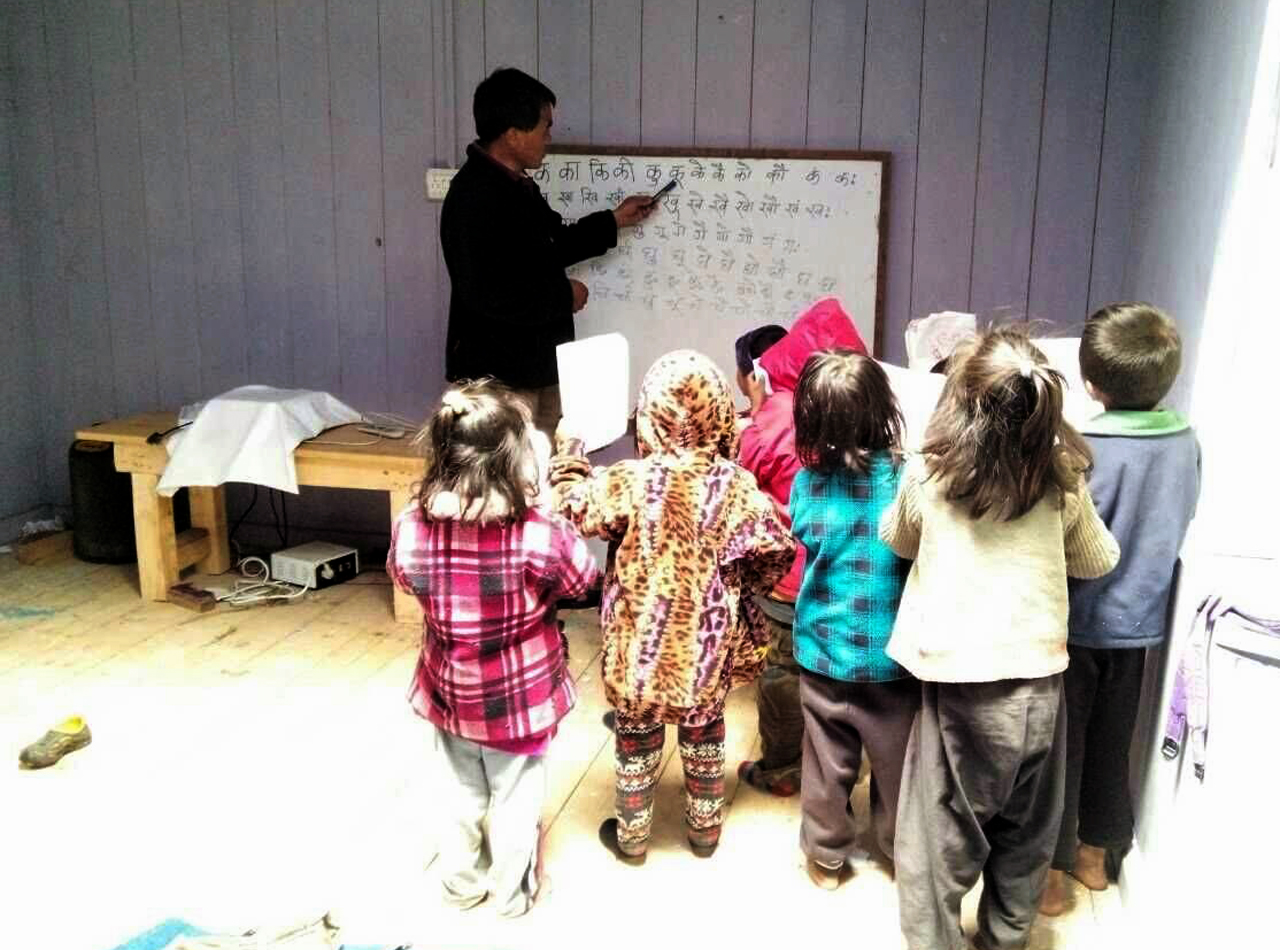

It is no exaggeration that only private schools and a handful of public schools in higher socio-digital structures have found refuge in the remote forms of teaching and learning activities as the novel phenomenon of academic practices is largely restricted to wealthier families in urban areas. But, for millions who belong to rural areas and low-income, vulnerable and marginalised groups, the transition has especially taken the heaviest toll.

This means those who do not have access to technology or lack the resilient learning engagement opportunities to educate themselves are at higher risks of falling behind not only academically but also socio-emotionally while others are flourishing. Further, the loss of income opportunities faced by multidimensionally poor households due to the pandemic has added to the woes.

A report prepared by Unicef in August last year has well documented how distance education compelled a massive number of students in lower economic households to suffer an acute learning crisis amid the pandemic, thus imposing a vast equity gap. According to the report, around 463 million children worldwide remained cut off from the education system, mainly due to a lack of remote learning technology at home. Of them, 147 million children belonged to South Asian nations alone.

The report further revealed that three out of four of those residing in rural areas were among the hardest hit and shut out from the educational opportunities irrespective of their nations’ economic development index while the reality in underdeveloped and developing countries, particularly for poor economic families, could be even harsher. In another report, Unicef estimated that more than two-thirds of Nepali schoolchildren remained unreached from digital or broadcast learning policies in the nation.

What is clear is that learners from low-income and illiterate family backgrounds across the globe have fallen significantly behind, thus magnifying the possibilities of high dropout rates, early marriages, child labour and violence against them. Therefore, Unicef has stressed the revision of distance learning policies in all countries to protect children from the loss of learning time and ensure them their universal rights to free education, justice and social equity.

Bridging digital divide

An invariable consensus among intellectuals is that technology can be a major enabler for change due to its dynamic capacity to continuously produce novel ideas and practices for educational development. There has been considerable debate about its impacts on societal affairs, educational activities and the workplace. Yet, many children who are from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds are unable to reap the benefits.

In view of closing the long-standing digital divide among its populations, the adoption of digital technologies has remained one of the core developmental agenda in Nepal over the years. In this regard, Nepal has continuously recognised the roles of information and communications technologies (ICTs) in education, health, economy, and governance among others but the policies have seen little progress.

The Broadband Policy (2015) aimed to connect all districts of Nepal with wired and unwired internet facilities by the end of 2020 in coordination with the Nepal Telecommunications Authority. Also in this line, the ICT Policy (2015) envisaged graduating Nepal to the top second ICT development index. Further, overhyped national policies such as the ICT in Education Master Plan (2013-2017), School Sector Development Plan (2016-2023), and 2019 Nepal Digital Framework have envisioned to promote educational sectors to the world standard by integrating information and communication technologies in education delivery, governance and management mechanisms. These policies also aimed to equip all the schools and colleges with proper ICT labs and establish necessary training centres across the country to impart needed training for administrators, educators and students. At the core of these policies, particularly SSDP and NDF, there is a high expectation to enable Nepal to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals and to reach the goal of becoming a middle-income country by 2030 through inclusive and equitable educational efforts. But, sadly, the Economic Survey 2019/2020 shows among 29,707 public schools across the country, computer facilities are available in 8,366 schools whereas only 12 per cent of the schools have computer facilities with internet connectivity.

Further, according to the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019 (NMICS 2019), only 15.4 per cent of households were found having ownership of computers, 84.6 per cent with mobiles, 51.1 per cent with exposure to the internet, and minimum ICT skill with 14.6 per cent (15-24 years age group). The data do not explicitly mention the quality of digital devices owned, their compatibility with the internet functioning as well as available ICT infrastructures. These figures, however, tell a complex story about the long-standing killer digital divide among different age groups, genders and socio-economic classes in Nepal.

Similarly, as of Covid-19 Education Cluster Contingency Plan 2020, prepared by Nepal Education Cluster, of the total 8,126,046 students enrolled in from pre-primary to secondary schools (up to grade 12) throughout the country, only 1,093,394 had access to the internet and 3,958,270 to other media while children having no access to any educational technology were 2,357,959 with 995,090 children at higher risks. The report also revealed that 45 per cent of Nepali school children lacked any technological means to support remote learning at home.

On the other hand, the latest data maintained by Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) shows that almost 87.19 per cent of the Nepali population (over 26.35 million) have access to the internet from any digital device from home while 7.66 million populations were reported to have 4G access. The NTA has also claimed to have made 4G services available in all 77 districts of Nepal. Although the data show the internet and technology penetration has dramatically skyrocketed over the years, the functional capacities of the larger population seem still miserable. If we have a closer look at the status of the Nepali population in terms of their access and ICT skills, the country still has a long way to go.

Who shall do what?

The government has proposed to allocate Rs 1.2 billion in the fiscal year 2021/2022 for alternative modes of teaching and learning plans—television broadcast or alternative online portals. It has been promised in the announcement to equip all the public schools with necessary technology and free internet broadband facility within two years and 60 per cent of schools by the end of this fiscal.

The government has claimed that the major objective is to bring all unreached students on board the mainstream education system as a response to the education crisis during the pandemic. It, however, seems that the government has shown little interest to timely put in place the learning opportunities for the neediest school-age children, thus further imposing on them silent suppression and robbing them of their universal right to childhood and education needed for a brighter future.

It is in times of crisis that human challenges become aggravated. Therefore, everybody from an individual to intragovernmental, development partners and humanitarian agencies need to understand that the virus-induced crisis is a stark reminder of humankind’s need for equity and solidarity. Missteps in responding to the educational crisis may cost us the heaviest price, not in the distant future.

Therefore, it is vital that we explore the most possible solutions to bring the lost generation on board the mainstream education recovery policies and keep education systems resilient even for the potential future disruptions caused by any other pandemic and disaster. For this to happen, the government must feel the urgency to allocate enough funding to get the educational technologies to the hands of disadvantaged children and enhance their capabilities to live the life they value.

It is equally paramount to learn lessons that schools do not rely on only one mode of distance learning to reach out to all the children. As the pandemic is unlikely to go away any time soon, it would be wiser to focus on expanding access to other forms of pragmatic learning as a long-term priority to save vulnerable children from further falling behind.