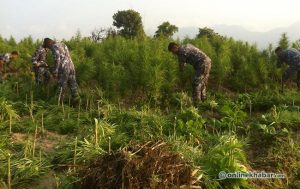

When the news of two police officials being a part of a marijuana awareness fair in Dhankuta of eastern Nepal appeared on the front page of a national daily, it caused a lot of uproar among activists. As marijuana in Nepal is still deemed illegal, the police officials were apparently punished later.

“The police were only there because they wanted to respect the invitation from the local ward chairs,” says Rajiv Kafle, a cannabis rights activist. “When I was inaugurating the event by watering the cannabis plant, the police officials left the area as a sign of protest. The news was a bit overblown.”

This happening in the midst of the government looking at opening marijuana cultivation for medicinal purposes has started a discourse about legalising marijuana again.

While activists and industrialists want the government to start looking at legalising marijuana in Nepal completely for business purposes, the government officials say that for now, their plan is only to work on growing it for medicinal purposes. But, the activists are accelerating the advocacy.

One step at a time

“We want to see where this goes first. Things like this can’t happen overnight,” says Bhisma Kumar Bhusal, a joint secretary at the Home Ministry who also looks after the Drug Control Section there. “We want to conduct evidence-based research to see if opening the use of marijuana in Nepal for medicinal purposes is plausible. Only then can we think about recreation.”

The Home Ministry says the proposal to open marijuana cultivation for medicinal purposes has reached the Council of Ministers. Supporting them are health and finance ministries. A concept paper has also been prepared by the Home Ministry, which is being taken to other ministries for suggestions and approval.

“The concept paper is now at the Law Ministry. We’re waiting for their review, after which we will start approaching government bodies to conduct research,” says Bhusal.

Hope for change

Activists see opening the use of marijuana in Nepal, at least for medicinal purposes, as a positive thing as they believe that once it happens, they feel it might be seen as less of a taboo by the general public.

“We want people to stop stigmatising it. This is something that has a lot of use. It’s great the government has started to see that marijuana in Nepal has potential,” says Kafle.

Health Minister Birodh Khatiwada’s personal secretary Madhav Timilsina says things are looking positive. He says a privately-registered bill at the House of Representatives is being discussed at the grassroots level.

“The ministry is working in tandem with other ministries to see how legalising marijuana in Nepal can be done in an effective manner. The minister is focusing on creating a proper mechanism,” says Timilsina.

Bhusal from the Home Ministry also says creating a mechanism is what they want to do and try to replace opioids that are being given to patients.

“We are trying to see if that is possible,” he says. “We want to see if we can stop giving methadone and use cannabis instead. For now, these are just on paper we need to conduct multiple research.”

Hemp for the win

Another way that can end the stigmatisation of marijuana in Nepal, according to Kafle, is the promotion of hemp products. He believes most people only know it as a drug and are scared to talk about it. He believes once people start to realise the help, another name for the marijuana plant, can be used for more than just smoking, people’s mindset will change gradually.

“When we went to Dhankuta during the marijuana awareness fair, we took with us hemp products. Seeing them for the first time, the locals, who only grow marijuana to sell, were pleasantly surprised. People from that small area bought the products worth Rs 70,000 in three days,” Kafle says, adding the activists want to host more fairs displaying hemp products.

The hemp market is quite big too. According to Ganesh Aidi, the vice-president of the Hemp Association of Nepal, hemp products worth Rs 2 billion are exported every year to 83 countries around the world.

“This is what we have been able to do without help from the government,” says, adding they pay taxes to the government stating they produce these products from allo, a tall, stout and erect herb also known as the Himalayan nettle.

Aidi believes that if the government encouraged hemp production, the industry would boom.

“If plantation of hemp plants were encouraged, it would help boost Nepal’s export. We believe we could export products worth Rs 1 trillion if the situation was more favourable,” says Aidi. He says the industrialists just want the government to legalise marijuana in Nepal for such commercial purposes.

Kafle believes the hemp industry’s growth would encourage more people to grow marijuana in Nepal to extract fibre to make threads for the hemp producers.

“This would mean more money for the poor. It’s a win-win situation I feel,” says Kafle.

Encouraging hemp plantations would generate more interest among the youth too who would create new ways to make newer products. Women in Dang have already started to do that by making bath scrubs out of hemp.

“We understand innovation is taking place and how much it would help boost the economy, but for now, there is no plan on legalising plantation for hemp,” says Bhusal.

Further research is soon to be conducted by NAST, says Bhusal, adds the government also plans to allow universities to conduct research on the uses of cannabis.

“I know that some students from Kathmandu University have asked permission for genetic profiling. These are positive steps,” says Kafle.

But, legalising the use of marijuana in Nepal for recreational purposes is still farfetched. Even though people like former PM Jhalanath Khanal have talked about it and openly stated that it should be open to using given people are careful, at the government level, a lot of work remains to be done.