Nepal Open University was established to expand access to higher education to the masses. But, recently, a lack of government interest and political appointments have shaken the organisation to the core as people have started to question its existence.

It has been over six months since the university has been without its academic council, leaving the future of thousands of students at risk. When vice-chancellor Lekhnath Sharma and registrar Kamal Dhakal’s term finished in June 2021, it took the university eight months to replace them with Shilu Manandhar Bajracharya and Govinda Singh Bista respectively.

Bajracahrya was the dean of the Faculty of Management and Law, which is without a dean since she became the vice-chancellor. Similarly, the Faculty of Social Sciences and Education and the Faculty of Science, Health and Technology are also without deans since Ram Chandra Paudel and Indra Bahadur Karki finished their terms in office. Subject committees are also dormant. This is due to the vice-chancellor and registrar not being on the same page, say stakeholders.

The vision

Nepal Open University was established in 2016 because a lot of people saw a need for it. The university envisioned taking The Open University in England as the benchmark. The plan was to make it as great as the one in England.

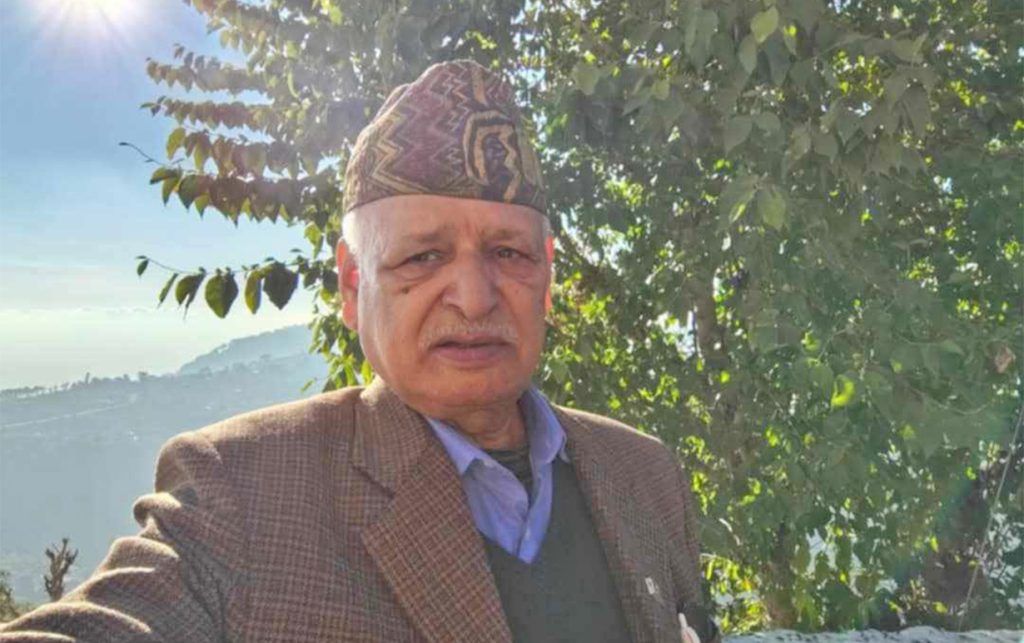

The idea to start an open university was put forward by educationists Man Prasad Wagle and Bidya Nath Koirala in 1993. In 1996, a committee was formed by education secretary Jayaram Giri to study the possibility of such a university. Both Wagle and Koirala were parts of the committee that recommended that the government start one.

In 2001, the government even included it in the policy and programme and set aside a budget for it. But, the Rs 9.9 million set aside for the university was transferred to Tribhuvan University to pay part-time teachers.

After that, a budget of Rs 2.5 million was set aside for Nepal Open University in 2005. But, the fund was used to set up a workshop by the University Grants Commission where professors from open universities from SAARC countries participated in. Koirala and Wagle even prepared a report of that workshop.

In 2012, an open university infrastructure development committee was formed by then Education Minister Dinanath Sharma. But, the committee talked more about politics than about education, says Wagle, who was a part of the committee. But, he did not stop as he continued to be vocal about the need for an open university in the country.

Even the Non-Resident Nepali Association had decided to help set up the university by providing financial, physical and technical support. The NRNA had even signed an MoU with the Education Ministry in June 2012.

The association had even demanded that its member be the vice-chancellor of Nepal Open University. But, that did not happen. Then Education Minister Giriraj Mani Pokharel appointed Lekhnath Sharma and Kamal Dhakal, both close to the Maoist Centre, the vice-chancellor and registrar respectively.

Reasons for the current situation

It has been six years since Nepal Open University was established. But, currently, it is in a paralysed state. The main reason for this is political appointments.

Power-sharing among parties means appointments of key personnel in the university take a long time. Sometimes, even if appointed, when two officials are from different parties, work is not done efficiently because of a conflict between them.

The current vice-chancellor and registrar were appointed eight months late. Moreover, Bajracharya is close to the Nepali Congress and Bista to the Maoist Centre.

According to Nepal Open University Act, 2016, the academic council is tasked with appointing deans. But, because the vice-chancellor and registrar are from two different parties, things have hit a brick wall. As the university does not have deans, it also has not been able to hold a single meeting of the academic council.

Educationist Suresh Raj Sharma says it is quite disheartening to see a university opened to cater to those from rural Nepal without a dean for such a long duration.

A former dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences and Education, Paudel says it was evident that political appointments were destroying Nepal Open University.

“It is clear that the political conflict is the reason why deans aren’t being appointed,” says Paudel.

He feels unless the university is free from politicians and politics, nothing will change.

Chancellors at fault

Educationist Bidya Nath Koirala says the main reason for the state of Nepal Open University is the chancellor, who is the country’s education minister.

“The current vice-chancellor is someone who the chancellor didn’t want. That is why things aren’t going as smoothly as possible,” says Koirala.

Academicians associated with Nepali Congress and CPN-UML were nominated for the position of the university’s vice-chancellor. Since there was no one from the Maoist Centre, Education Minister Devendra Paudel, who is also Nepal Open University’s chancellor, tried to hold the appointment. But, after pressure from the prime minister, he had to give in and Bajracharya became the university’s vice-chancellor.

“It’s hard for Bajracharya to work because the chancellor doesn’t support her and neither does the registrar who is from the Maoist Centre.”

Wagle also blames the chancellor. He says faculties not having a dean was a joke.

“When will the chancellor take accountability about this,” says Wagle.

Former vice-chancellor Sharma says that since a vice-chancellor cannot overstep the chancellor, there is nothing Bajracharya can do.

“When you can’t even appoint a dean, there’s nothing you can do,” says Sharma.

Students suffering

Nepal Open University currently does not have an academic council responsible for the curriculum, credit transfer, and credit accumulation. Consequently, a lot of work in the university is on hold, says Registrar Govinda Singh Bista. He says there have been constant talks about appointing the deans, but things are yet to be finalised.

Indra Bahadur Karki, who previously served as a dean of the Faculty of Social Science and Education and acting vice-chancellor, says the students are suffering the most out of all this. Former vice-chancellor Sharma says appointing deans to the faculties was the first thing the university needs to do.

Another problem with Nepal Open University is that it only opens admission to 50 students per subject. This, Wagle says, makes no sense as there are thousands of students in the country who are in need of a university like the NOU.

But, following political tensions in the university, the NOU does not even get 50 students, which is a sad thing, says Wagle. “The university is losing credibility,” he says. “If things don’t improve, the university will have no students in the future.”

Educationist Koirala says the university was established for those who wanted a degree while working. He says he has asked the university to work on starting credit and non-credit courses and giving research-based degrees.

“But, we couldn’t do much,” he says. “We even proposed them to start sociological courses on different religions, but even that didn’t go ahead. If you aren’t from a party, your opinions won’t be taken, it seems.”

Nepal Open University is yet to publish the results of students enrolled in 2019. This also paints a bad picture, say stakeholders.

No building, no rights

In a paralysed state, Nepal Open University has not been spending its budgeted amount either. Former acting vice-chancellor Karki says if the university had spent the Rs 400 million set by the government in recent years, the university would have had its own building. But, currently, the university is renting a building at Rs 6 million a year.

The government has also not allocated the NOU professors and assistant professors. As of now, the university is only allowed to appoint lecturers, assistant lecturers and other administrative officials.

Wagle says he was amazed by how the government was trying to run Nepal Open University.

“How can you open a university and not give seats for professors and assistant professors? It makes no sense,” says Wagle.

This story was translated from the original Nepali version and edited for clarity and length.