On the evening of May 8, 2009, Hotel Soaltee Crowne Plaza in Kathmandu was abuzz. As SUVs and sedans converged at Soaltee Mode, leaving the dusty Kalimati road behind to enter the hotel premises, passersby hardly took notice.

The thick foliage surrounding the hotel, after all, stands as a buffer against the pettiness of the city, while containing whatever opulence it exudes within itself.

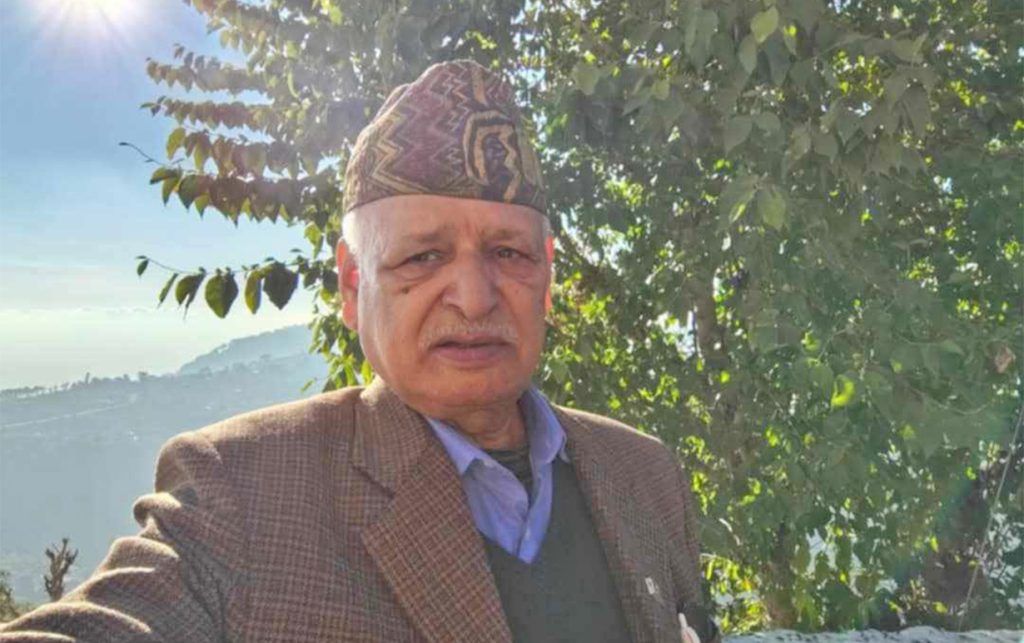

As MD of KIST Bank, Kamal Gyawali would not have been anywhere else that evening. This was only one of the many plans of action he had charted out to become a dominant player in the Nepali banking sector. In 2002, he started KIST Merchant Banking & Finance with an initial investment of Rs 50 million. The company’s tagline was “Power to Succeed.”

In a short span of time, KIST had, indeed, succeeded under his leadership. Just a year ago it distributed cash dividends of up to 10% to its shareholders.

Seven years after KIST opened its first account, on that evening, it was going to formally announce its transformation into a grade ‘A’ commercial bank. Gyawali was at the centre of its universe.

“This is only the beginning,” Gyawali, perhaps, said to himself.

As the night progressed, the guests, mainly top players of Nepal’s banking sector, mingled with interim passion largely caused by the free-flowing alcohol in the room. Two invitees, however, had decided against going to the party.

A day earlier, Sashin Joshi and Surbir Poudel, the then chairmen of Nepal Bankers’ Association and Securities Board of Nepal, had both attended the formal launch programme. “Major challenges lie ahead for KIST, especially in the area of governance,” both of them had said at the launch.

Little did anyone present at the event know that few years later, this would be the very trigger that would lead to the dramatic collapse of KIST Bank, and along with it, the ambitions of Kamal Gyawali.

Just three years ago, Gyawali was counted among the top bankers in Nepal. Under his tutelage, KIST bank expanded its operation with 51 branches all over the country. In the crowded banking sector of the country, KIST usually held its position among the top 10.

Kathmandu-based mediapersons was quick to take note. Gyawali’s success story was such that most media outlets were keen on writing about it. Even Gyawali himself had a savvy media persona.

He had, among others, strengthened his ties with media houses by maintaining a strong business relationship with them.

Three years and several bad decisions later, Gyawali’s legacy lives in infamy as cases of loan fraud come to surface. Gyawali and his wife Gauri are currently on the loose after a Patan Appellate court ruling against both.

***

Gyawali first came to Kathmandu in 1995 to pursue his higher studies. Born to a middle-class family in Gulmi in western Nepal, he first took on odd jobs to support himself in the city.

According to his autobiography Karma, he had Rs 10,000 with him when he first came to Kathmandu. He then worked as a teacher for sometime. In the seven years leading to the commencement of KIST Merchant Banking & Finance, Gyawali had succumbed to the ways of the big city. For Gyawali, the city itself existed as a living advertisement of dreams and possibilities.

But without hopefulness to humble him of his burning ambition, Gyawali took his chance and opened KIST Merchant Banking & Finance in 2002, only seven years after he first came to Kathmandu.

In the next seven years, Gyawali increased the paid-up capital of the company to Rs 2 billion and upgraded it to a grade ‘A’ commercial bank. His net worth reached approximately Rs 3 billion as the success of his earlier finance company was carried over even after its upgradation to a commercial bank, however short-lived it may have been.

During those years, nothing could tie Gyawali down.

He had cashed in strategically on the booming real estate sector of the country. “There should be a revised list of billionaires in the country,” he had said to this scribe during 2008.

But Gyawali would not stop even if he was listed as one of the richest person in the country.

“He called himself a ‘businessman’ rather than a banker,” says a managerial staff, who worked with Gyawali at KIST Bank.

“He would talk about earning more all the time.” Several other colleagues also talk about this ambition. It was the same ambition, which had catapulted him to success. But others could see what Gyawali fell into, and the possibility of this ambition being the reason for his fall.

For Gyawali, KIST bank was a manifestation of this ambition. The gleaming glass-wrapped, seven-storied HQ of KIST bank at Anamnagar, commissioned by Gyawali himself, was the most striking display of this.

But huge profits and an ever-expanding banking empire was not enough for Gyawali. He wanted KIST to become an indispensable institution, such that if the bank were ever to fail, Singhadurbar itself would come to its rescue.

***

During late 2000s, high lending and low deposit collection triggered a liquidity crunch in the market. This had a massive impact on the local economy.

Investment in real estate increased as property prices soared. As the global recession of 2008, which was caused by the bursting of the housing bubble in the US, eventually impacted the local economy, the central bank ordered commercial banks of the country to limit investment in real estate to 25 per cent of their portfolio.

This directive considerably slowed down the booming real estate business.

This was bad news for Gyawali, who owed a major part of his success to investments in land and property across the country. “I don’t earn much from my salary,” he had told this scribe in 2008. “I earn more than thrice my salary from real estate.”

Gyawali had invested Rs 500 million in real estate by 2008. He owned shares worth Rs 2.5 billion, a majority of which (more than 4 million shares) was of KIST bank.

The same year, the price of KIST bank’s share rose to Rs 1,800 per share. But its value slowly declined during Dashain that year as the central bank failed to issue new banknotes in the market, worsening the liquidity crunch.

The following year, real estate business almost came to a halt. The liquidity crunch had brought the local economy down on its knees. These events challenged Gyawali’s ambition to expand his banking empire to a level no other banks had reached.

Then Gyawali made a bad decision, and another. And another.

“If he had sold his shares and properties which he had invested in, he could have saved KIST bank,” a close associate of Gyawali says. But he instead chose to wait out the slump. He then took more loan to clear out the outstanding ones.

In 2010, KIST granted a Rs 15.5 million loan to Kishore Dhakal, proprietor of a publication house named Jamarko Prakashan where Gyawali’s wife Gauri was involved. But Gyawali used more than half of the amount of the loan to clear his outstanding loans.

As the real estate situation worsened Gyawali took another loan. This time in friend Kishore Dhakal’s name.

The loan worth Rs 10.3 million was taken against assets of Jamarko publication from Siddhartha Development Bank. The bank’s chairman Shekhar Aryal was a close friend of Gyawali.

Kamal Gyawali and Shekhar Aryal were the best of friends during the time. The friendship grew stronger during passionate talks about business and investment and shared vacations.

For CEO Dipendra Karki, Gyawali was a mentor.

But even the loan could not help him recover the losses incurred from the real estate market, which showed no signs of rebounding.

The friendships also quickly turned sour.

As Gyawali took more loans to cover the losses in his investment, he not only lost track of personal finance but also turned those close to him against him. His outstanding loan from Siddhartha had not been cleared. He even failed to pay its interest.

The central bank took note of this irregularity after a complaint was filed against him. In 2012, the central bank concluded that Jamarko’s assets had been over-valuated by as much as Rs 35 million when loan was issued against it .

The central bank soon notified the CIB and charged Kishore Dhakal who signed the loan deal. During investigation, the CIB found out that Gyawali had used the loan himself. It arrested Gyawali’s wife Gauri from their Maharajgunj residence. Gyawali, however, was already on the run.

As the embezzlement dominated the headlines, stakeholders lost confidence in KIST bank. It was not only Gyawali, who had been charged but several other colleagues were also found to be involved. Account holders queued to withdraw their money from the bank. The survival of the bank was in question.

But no one could save the bank from from its doom.

As Prabhu Development Bank acquired KIST bank and commenced operation as Prabhu Bank in 2014, KIST is now part of history, one riddled with bad decisions and managerial oversights.

“We had worked hard to bring back KIST bank on the right track,” says a former executive of the bank. KIST bank had an illustrious team of bankers and managers, which consisted of Gyan Bahadur GC, Dr Danda Pani Paudel, Achyut Raj Joshi, BN Gharti and Bal Kumar Pandey, among others. But the mismanagement of the bank had already become irredeemable.

***

A day before the celebratory party at Hotel Soaltee Crowne Plaza, at the inauguration of the bank, the then deputy governor of Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), Bir Bikram Rayamajhi, had curtly responded to both the chairmen’s’ concerns.

“No one needs to comment on NRB’s governance,” Rayamajhi had said at the event.

“We see no problem in KIST’s management. We have given permission for it to commence as a commercial bank looking at its top-notch governance.”

Rayamajhi had perhaps, spoken out of passion that evening. Gyawali had publicly lobbied to make him the governor of NRB. Eventually, as Dr Yubraj Khatiwada became NRB’s governor, he perhaps took it personally that Gyawali had lobbied for an opponent.

The central bank usually takes over the management of a bank and its assets if it falls into crisis. But perhaps as a final irony in the tale of the downfall of an empire, the central bank charged it instead of managing the crisis.

During those final days of KIST Bank, Kamal Gyawali had no one to save him. As the central bank turned a blind eye to the crisis, no politician he had lobbied for nor a colleague who he had good working relations with, could be of help.

Singhadurbar, probably, did not even take notice.