For the past one week, Binod Pathak, Sumiktra Shrestha and Ashok Thapa of Budhanilakatha Municipality in Kathmandu have been scouring their neighbourhood every afternoon in search of used tyres. The environmental science, social sciences and business studies student team has a plan to reuse the tyres to plant trees.

The trio launched the initiative and learned about the reusing technology on their own. However, it was their municipal government that triggered the idea.

The initiative was part of Yuwanilakantha, the municipality’s campaign launched around two months ago to mobilise youth for development.

An effort to rebrand the city

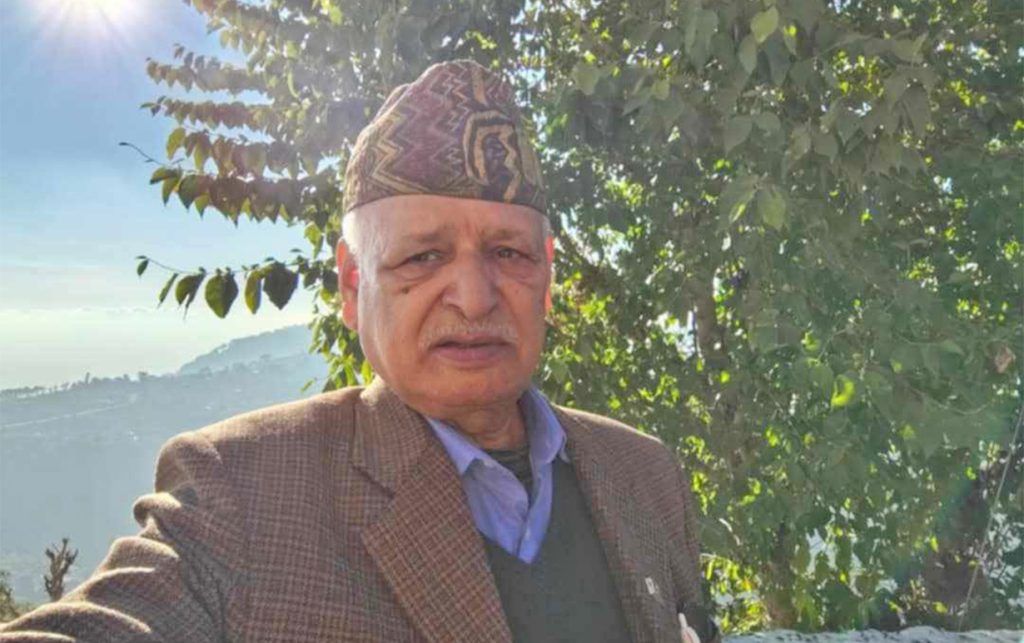

Elected Mayor of the newly-established Budhanilakantha Municipality last year, Uddhav Prasad Kharel was staring at challenges galore. Kharel, who led the then village around two decades ago, wanted to make his citizens feel that they now live in a municipality.

As the municipality began drafting plans for the new fiscal year, Kharel wanted to make some visible changes. He wanted to make his city different from others in the neighbourhood. Kharel concluded that he could achieve it by mobilising the skilled youth of his city. Accordingly, he directed his secretariat to design a ‘unique’ programme.

This is how Yuwanilakantha was born. This campaign, if you go by its name, sounds quite rebellious—it wants to make the ‘old’ city (‘Budha’-nilakantha) ‘young’ (‘yuwa’-nilakantha).

Mayor Kharel says Yuwanilakantha is a campaign that aims at inventing a new brand so that people in and outside the city recognise the local government as a changemaker.

In the first phase of the campaign, his secretariat enrolled and trained its first cohort in various activities. The participants are still developing and implementing various programmes for the development of city.

“We organised a 16-day residential research workshop for 19 youth representing all wards of the city,” the Mayor’s Office Secretary Sumit Kharel, who also leads the campaign, informs, “After the training, the youth have been divided into four groups to carry out research, and work in different sectors.”

The first four days of were devoted to training. “The participants were trained in a wide range of issues from religion and spirituality to the Sustainable Development Goals by thematic experts,” he briefs.

Then, in the next 12 days, the youth conducted research and prepared a plan of action to solve problems in their respective sectors.

“The research topics were related to burning issues of our city such as solid waste management, conservation of cultural heritage, management of public health facilities and entrepreneurship development,” campaigner Kharel says, “The research teams ended up with interesting findings and we have forwarded the reports to the municipality.”

Research-based activism

Based on these findings, the participants have planned various projects and begun implementing some of them.

For example, Shrestha wants to enhance good governance in the city. “My team is planning to interview city officials and other stakeholders about services of the local government and circulate them among public via various YouTube channels and Facebook pages.”

Another team has concluded that vermicomposting is also possible in the city. “It has two benefits—it can help the municipality control the problem of stray cattle whereas it can also be a model for sustainable agricultural practice,” informs Nimesh Thapa.

However, all of them are not immediately executable for lack of budget. “We do not want the municipality to sponsor these programmes,” campaigner Kharel says, “We will find sponsors on our own to implement them. Otherwise, we want the municipality itself to run the projects.”

Pressure group vs executor

In the brief journey of Yuwanilakantha, campaigners have found themselves confused—whether they are just another pressure group like local clubs or they have some power to execute the projects on behalf of the municipality.

Campaigner Kharel accepts that some of the projects that his group has envisioned are “beyond the circle of influence” because Yuwanilakantha, legally, does not have any independent status and authority to enforce its decisions.

What the campaign can do is to convince the municipal leadership to shape its programmes in the way the campaigners want. But, campaigner Kharel explains that the Mayor has not taken any concrete initiative to implement recommendations of their research so far. He, however, is hopeful that the leadership will gradually learn the importance of research.

Mayor Kharel also agrees with the campaigner. “The first objective of my dream was informing the youth about problems of our municipality and motivating them for the solutions,” he says, “This objective has already been met.”

“The municipality is yet to organise various mechanisms to implement recommendations of the research,” the Mayor claims, “Yuwanilakantha is the Mayor’s brainchild. Therefore, its recommendations will be included in the municipality’s policies and programmes.”

Ward chairs of the city have also extended support to the campaign. One of them is Ward 10 Chair Nawaraj Bhattarai. “I think the campaign will be more effective if each ward has a unit of Yuwanilakantha to work with them,” Bhattarai, the youngest among 13 ward leaders, says.

“We want this campaign to aim at making youth responsible for the development of their communities. They should promote community-based development,” he adds, assuring the support of ward committees.

The way forward

As suggested by Bhattarai, the campaign wants to expand all over the city, according to campaigner Ashok Thapa. “Our target is to produce 500 active community youth leaders within five years,” he says, adding, “We will call for applications for the second cohort within next four to five months.”

“In the meantime, neighbouring Tokha Municipality’s Mayor invited us to his office to share our ideas,” Thapa informs, “After the meeting, he said he wanted to introduce a similar programme in the municipality.”

“Yuwanilakantha was an experiment and it proved successful,” Mayor Kharel says, “This campaign addresses two critical problems at once—whereas the local government has turned inefficient for the want of skilled human resources, many qualified people are wandering jobless. This campaign mobilises youth to work for the local government.”

Kharel says his team will support the campaign as much as possible. “We will continue this campaign and make sure that youth participate in the policy formulation process of our municipality.”