Rewati Gurung was well-exposed to the western world during her formative years. She studied English literature in her master’s first and moved to development studies–both courses were dominated by theories and examples from America and Europe. Consequently, her brain was programmed to think that foreigners, whites in particular, were better than Nepalis.

In 2015, Gurung attended a summer school in Finland, during which she learned about the impacts of ‘Finnish Baby Box‘, a cradle along with a package of clothes uniquely designed for newly born infants and their moms after World War II. Three years later, she ordered one such box to be delivered to her in Kathmandu, all the way from Helsinki. Having seen some women-led enterprises in Nepal, Gurung was thinking if any Nepali woman could replicate the Finnish model. It was a part of her personal research.

Gurung’s ‘colonised’ brain was expecting some ‘scientifically-designed’ and ‘real European’ items in the box. “But, I was shocked…,” when the filmmaker-cum-enterprises narrates it after nearly two years, the ‘shock’ is reflected on her face again, “… because that box had something exactly like our bhoto.” [Bhoto is a typically-designed homemade vest for children in Nepal.]

That ‘Finnish bhoto’ brought a paradigm shift in her mind. At first, it compelled her to research why Nepali and Finnish societies have the same kinds of apparel for babies. After completing the research, she decided that she would follow, not replicate, the business model and design a ‘Nepali’ baby box instead. Once the white-is-better thinker, Gurung today owns a startup named Kokroma that manufactures and sells Nepali-design baby clothes.

The science of Nepali baby garments

The findings of Gurung’s informal research were interesting. She got answers to the questions like why a bhoto usually has an inner layer (bhitri), why it has laces (tunas) instead of buttons, and why they fill pillows with mustard seeds.

“From old grannies in my extended family and neighbourhood, I learned that the inner layer of your bhoto has two functions: it absorbs sweat, and it protects the baby’s soft skin from the less soft outer,” she elaborates, “Likewise, the laces were scientific because the kids could swallow buttons.”

She also learned that the Nepali society preferred pure cotton for baby clothing “because it is a natural fibre; it does not cause any harm even if the baby chews and swallows it.” Similarly, mustard seeds are filled in the pillows because they help the baby put the head in a right posture. “You cannot use millet seeds or anything similar because millet easily breaks into dust and it has a certain smell that makes the infant sneezing.”

Having learned the rationale of the old science and seen Europeans following the same, Gurung then decided to produce a ‘Nepali baby box’. She initially thought she would also use cardboards to make the bed/box as it is handier than a kokro, a traditional Nepali bamboo crib. “But, as I began exploring, I found several advantages of the kokro,” she explains, “The flooring in Nepali houses is not as fine as it is in other countries. Cardboards are not much sustainable on such floors.”

Therefore, Gurung not only included a kokro in her production list, but she also made it her brand name. [‘Kokroma’ means inside a kokro.]

Empowering women

Gurung says there is another story behind the establishment of Kokroma, besides her summer school experience.

After attending an all-women filmmaking workshop in 2017, Gurung independently produced a documentary featuring Drichu, a local clothing brand of Bauddha. Building on this experience, Gurung and Finnish filmmaker Gary Wornell applied for a World Bank-assisted project run by the Poverty Alleviation Fund. They were selected and assigned to make documentaries featuring women entrepreneurs from across the country.

“Between December 2017 and February 2018, we travelled from Taplejung to Dailekh and collected stories about Dhaka weaving, Mithila art, hemp clothes and bamboo baskets,” Gurung recalls, “Overall, what these women were doing was impressive, but I was not happy for them because they did not have access to the market. The sustainability of their business was questionable.”

Gurung compared the businesses with Drichu, also led by a woman, and found “it was far successful because it had a market. It was established as a brand.” She then thought about what other enterprises could be appropriate for starting-up women in Nepal. That was the time she remembered the Finnish Baby Box and ordered it.

“Yet, it was clear that I was not going to be an entrepreneur. That was not my cup of tea; I hated maths throughout the school. There was no one in my family from this background,” she says, “I was thinking it for Nepali women in general.” But the ‘shock’ [discussed above] brought her here.

Because the initial idea was empowering women, Gurung says she has been keeping it at the centre. “During my research, I found that many prisoners, including many women, are involved in weaving cotton, but they did not have sufficient market. Hence, I approached the Central Jail in Kathmandu for cooperation and we have become a market for them till today.”

Kokroma employs six tailors, all women, and Gurung claims she pays them a ‘fair wage’.

‘Not a bed of roses’

While Gurung believes in a fair pay policy, it seems her products sold well from day one. “Nope, they didn’t,” Gurung laughs before immediately wearing a sad mask on her face, “The first days were as frustrating as hell. By December 2018, we made 20 sets but no one purchased it. Then I approached my relatives.”

“One afternoon in February this year, I went to a relative with my set. She didn’t like it. I got disappointed.” Gurung went to a coffee shop in Bauddha “just to cool down.” She had the rejected apparel set in her hand.

“At the cafe, beside me appeared a foreign lady who asked me what I was carrying. I explained it to her. She listened to me carefully and gave me her email address, suggesting I could write to her if I would ever need any financial support for the project,” the woman recalls, “I didn’t believe. A five-minute meeting cannot lead you to any fund. Nevertheless, I wrote to her.”

After a few days, she got the response, a commitment to provide USD 15,000 as a grant in different instalments. Cristina Henriquez from the US has provided her USD 6,000 so far. Gurung hired her first staff and purchased seven secondhand sewing machines with Henriquez’ support. So far, in total, Gurung has spent around two million (USD 20,000 approximately) in the business.

In the meantime, Wornell, the Finnish filmmaker, helped her promote the products in the international market. He also designed the brand’s website and other publicity materials. Today, Gurung considers Wornell her mentor and an integral part of the team. The sexagenarian is living in Nepal for the next two years to study Nepali language, and she hopes to ‘exploit’ his expertise during this period for Kokroma’s promotion.

After passing through depressing days, Kokroma has just been a self-sustaining business, Gurung claims, adding her monthly revenue is Rs 200,000 whereas monthly expense amounts to around Rs 100,000 these days.

“But, there are still many challenges for startups,” Gurung says adding Nepali customers think that made-in-Nepal products should be cheaper than the imported ones irrespective of the quality. “The customers do not recognise and respect local brands and we want to change it.”

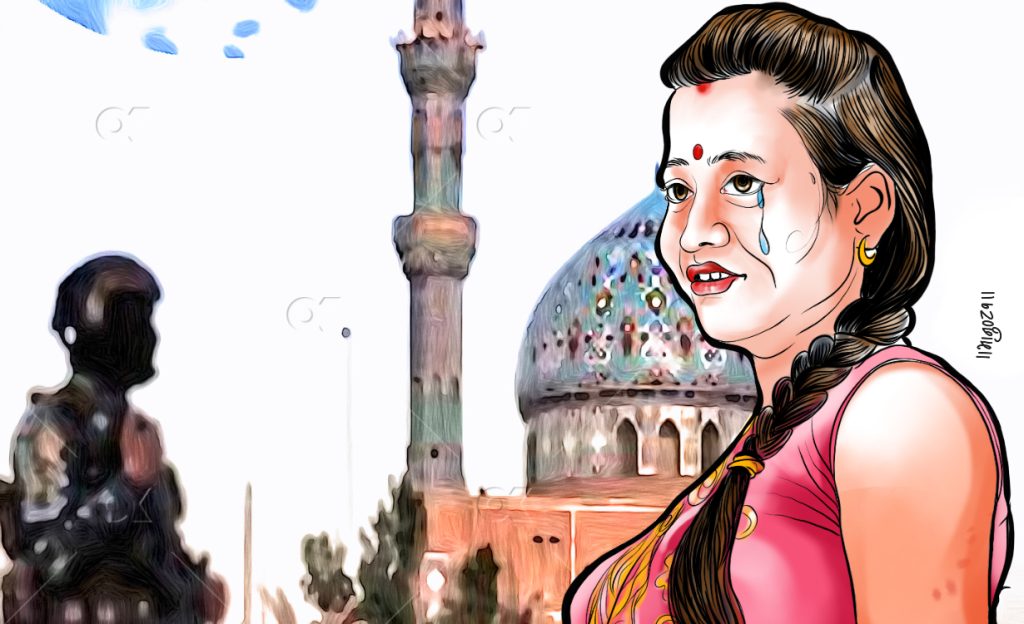

Photos: Courtesy Gary Wornell