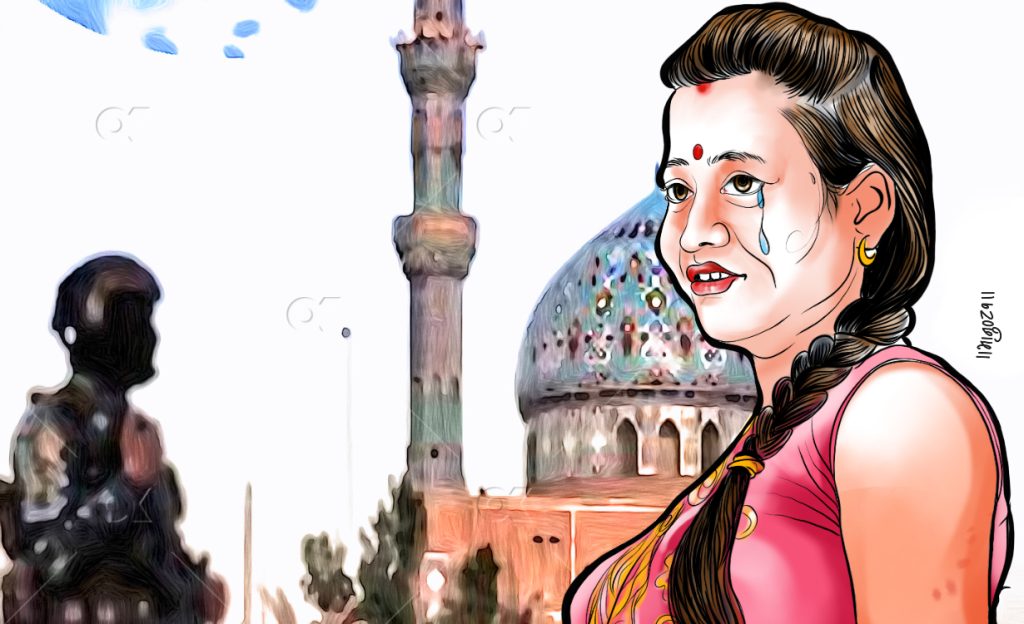

In a diverse country like Nepal that accommodates a large variety of castes, creeds, customs and opinions, the judiciary, being an integral part of the governance system of such a diverse nation, should reflect the diversity in itself too. But, when we talk about gender diversity specifically, we find that the Nepali judiciary is dominated by only a specific gender group.

In Nepali society, the nature of being argumentative is generally associated with men, and the bench which is already dominated by men, perceives female lawyers as being too less argumentative which creates a professional barrier for female lawyers that can lead to alienation of women from the legal profession. Similar kinds of other gender stereotypes and other variables of gender-based discrimination may aid to sustain existing gender apartheid in judiciary.

However, with so many women studying law with a determination to serve the country’s judiciary, it must change. Concerned government agencies need to introduce and implement effective policies to effect this transformation.

Gender justice in the justice system

Participation and diversity are directly proportional to judicial empowerment, impartiality and quality of judgments. Judiciary will not be trusted if it does not reflect the composition of society. According to the 2019 data recorded by the UNDP, women’s representation in the judicial branch of the government in Nepal is only 3.8 per cent; that also includes bailiffs and law clerks.

According to the data of the Judicial Council Secretariat, there are 394 judges in all tiers of the judiciary in Nepal, out of which only 14 are women, which is only 3.55 per cent of the total. The council in its appointments often ignores the principle of inclusiveness prescribed by the constitution of Nepal, 2015, according to which, vulnerable groups like women, Madhesis, Tharus, Janjatis, Muslims and other marginalised groups need to be included in the bodies of the state that also includes the judiciary. But, we have examples where these principles were ignored and judicial appointments were flooded by male appointments.

For example, in 2016, the council recommended names of 80 persons for different designation in courts, out of which only four were women and other marginalised groups covered only 18.5 per cent of the total appointments. However, the legal roster had a considerable number of applications of women, Madhesis, Tharus, Janjatis and other marginalised groups. The irony is that Sushila Karki was the chief justice of Nepal then, the first woman to hold the high office. Statistics clearly show that women are not prioritised for judicial appointment despite their availability.

According to 2011 census, Khas Arya men constitute only 14.44 per cent of the population of Nepal, but they make up more than 85 percent of judges in the country. It is a matter of serious concern that a gender group that is already at the pinnacle of the so-called dominant class is dominating the judiciary of a country whose constitution very scrupulously has made provision for appointments on the basis of principle of inclusion.

Need for reforms

There arises a very relevant question on why we need such kinds of gender-based representation in the judiciary. During a research work performed by the International Commission of Jurists, the researchers talked to female civil litigants and criminal defendants about their experience. They opined that they found women judges with more strong reasoning capacity in the issues of women’s human rights.

The lack of inclusion of women is also directly associated with active reporting of sexual or gender-based offences in which survivors do not feel comfortable while taking their case to the court which is already staffed by male judges. When judges will be from different backgrounds, groups and genders, they will certainly deal with cases from their respective experiences. When a woman comes to the court for the trial, it is obvious that there should be a female judge on a bench to adjudicate the matter as she will be more aware of the hardship that women go through in their daily life.

There could be a whole different perspective in the same judicial decision that was rendered by a male judge as it is illustrated by the Feminist Judgment Project, in which hundreds of female law professors rewrote judicial decisions from a feminist perspective. Therefore, there is a need of women to sit as a judge in a bench to bring resilience in pervasive masculinity in the judiciary. Thus, we need to look for a more inclusive judiciary in all aspects of inclusion and in special reference to gender variables to ensure legitimacy in the eyes of the public, to ensure the quality of judgments and to ensure fairness in overall judicial procedures for each and every citizen, from any sexual group. An inclusive judiciary ultimately paves the way for an empowered judiciary.