Over the course of the past few months, banks and financial institutions have been hit with a liquidity crunch. Even though there is a demand for loans, almost all banks and financial institutions in Nepal have not been able to provide loans to people and businesses as they themselves are out of cash.

As of now, banks and other financial institutions in Nepal have issued loans of Rs 4.5 trillion. In the past four months alone, loans up to Rs 300 billion have been issued. But, despite this, there is a liquidity crunch in the country. This issue has resulted in the government now trying to stop the trade.

But, a key question remains: where is the money?

Easy question, difficult answers

Experts say while the answer is not as simple, the main reason for the liquidity crunch is the lack of deposits compared to loans. Nepal Rastra Bank governor Maha Prasad Adhikari blames the Covid-19 pandemic for the liquidity crunch.

“The economy is making a comeback post-Covid-19, and things like these are expected to happen,” says Adhikari.

That is understandable, but most of the loans that banks have issued have not been in the productive sectors. According to data, most loans have been issued for the procurement of consumable commodities.

According to the Banks and Financial Institution Regulation Department of the central bank, loans issued to procure consumable commodities have increased by 47 per cent in the past year. It means the liquidity crunch has also gone up significantly.

The department says that the commodity loan that was Rs 158 billion in 2019-20 increased to Rs 233 billion in 2020-21. The department says that the number is increasing even today, and so is the liquidity crunch.

Around six months ago, bank deposits were quite high, but lately, as deposits have gone down, issuing loans has been a huge problem. These loans were mostly investments in certain projects, which is good for the country, but with a lack of deposits, banks are running out of money.

The Bank Supervision Department’s director Gunakar Bhatta says the demand for loans increased at the end of June. This trend continues in the first months of the current fiscal year as banks kept on issuing loans to people and businesses, resulting in the liquidity crunch.

So, where is it being invested?

Two years ago, banks hardly issued loans on businesses that dealt with agriculture. Even though banks and financial institutions were told to issue 10 per cent of total farmers or farming businesses, banks found it really hard to do so. This resulted in many banks having to pay fines to the central bank.

But recently, almost all banks have started to invest in the agriculture sector by issuing loans to people and businesses. As the country wants to be self-reliant on agriculture, it wants more and more investments to be made in the agriculture sector. The government is so serious that it has put this in the monetary policy also.

In the past four months, agriculture-related loans have gone up by Rs 33 billion as it currently stands at Rs 357 billion. This is one of the major factors why the liquidity crunch is so sharp currently. Bhatta says as the government has prioritised the agriculture sector, farmers have been going to banks and taking loans to either start or expand their businesses. As banks offer concessions on loans for the agriculture sector, many people are taking these loans, says Bhatta.

“As the agriculture sector is commercialising itself, they require more investments and banks are providing that,” says Anil Upadhyay, the president of the Bankers’ Association.

While loan investment on agriculture has increased, the past few months have seen a drop in loans issued on behalf of shares. The loan amount on shares stood at Rs 106 billion in June. But now, the amount has gone down to Rs 102 billion. This is mainly due to the share market showing a bearish trend in recent months. The bearish trend and the NRB decision to put a stop on margin lending has been cited as the main reason for this dip.

Import issues

Consumable loans have also gone up, intensifying the liquidity crunch. These loans include personal loans, loans against fixed deposits, and business loans. Apart from these, credit card loans have also gone up as people have been using credit cards to pay for commodities, food and shopping. In the four months, credit card expenses have gone up by 35 per cent.

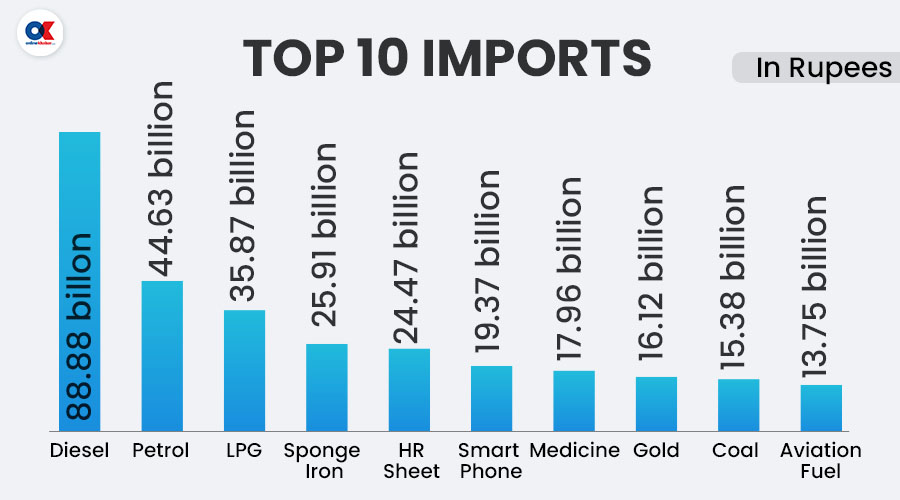

Another loan that has gone up in recent times is import loans. Experts say one of the main reasons for banks to be out of cash is due to the rise in imports. Almost all businesses offer loans to imports to bring things to Nepal. They give these importers around two months to pay up and that is one of the main reasons why banks are out of cash, experts say. An increase in imports has also led to a decline in the country’s foreign exchange reserves, which, in the long run, could be detrimental as remittance, since the start of the pandemic, has gone down.

To curb the liquidity crunch, the NRB, on Monday, introduced a new policy to control imports. While importers only needed to deposit 10 per cent of the LC amount in the past, now, they have to deposit the entire amount before they are allowed to bring anything into the country.

“Things will get back to normal once import decreases,” says Upadhyay. “Consumption loans have gone up due to excess imports. Once this is under control, things will go back to normal.”