On September 25, 2022, the Medical Education Commission conducted the entrance exams for DM (doctorate of medicine) and MCH (master of chirurgiae/superspecialist research degree). On November 2, the final results were announced along with an admission notice. Surprisingly, some positions in DM and MCH classes were not filled.

According to the data of the commission, it received no applications for MCH (heart surgeon), DM nephrology (kidney specialist) and DM hepatology (liver specialist).

The commission had fixed seven seats for cardiac surgeons as it wanted to hire one each of the superspecialist doctors at the BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences and Nobel Teaching Hospital, Biratnagar, three at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital and two at Bir Hospital.

For the DM, eight seats were allocated for kidney specialists. The commission wanted to hire one each at the College of Medical Sciences Teaching Hospital, Chitwan; Kathmandu Medical College, Sinamangal; Nepal Medical College, Jorpati; and Nobel Teaching Hospital, Biratnagar and two each at Manmohan Memorial Medical College and Bir Hospital in Kathmandu. The commission also wanted to hire one liver specialist at Bir Hospital but no one applied.

Similarly, in some other categories, only half of the number of seats have been filled. Out of 10 MCH neurosurgery seats allocated in various institutes and medical colleges, only five seats were filled. The details of the commission show that only four doctors have been admitted out of the 10 seats of the DM critical care medicine class.

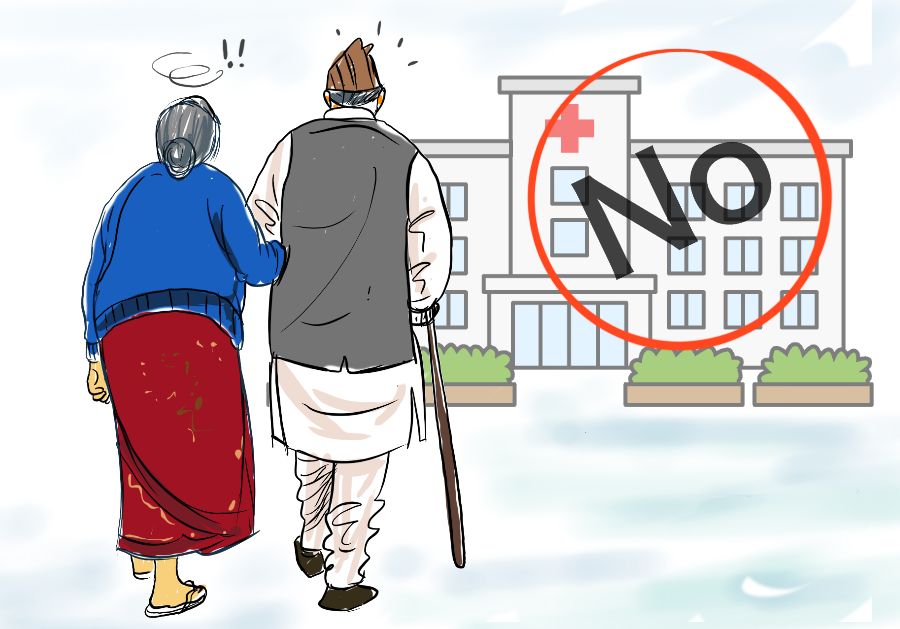

According to the experts, there have been very few doctors who study to become specialists in heart, kidney and liver surgery. The shortage of superspecialist doctors is bad news as heart, kidney and liver patients are on the rise every year.

Hard work doesn’t pay off

The commission’s vice-chairperson Dr Srikrishna Giri says students are not attracted to being specialist doctors in these sectors because of limited employment opportunities in Nepal. He says the lack of development of dedicated hospitals for heart, liver and neuro problems means the chances of students getting a job are low.

“They’ve seen others study hard to become specialists but not get jobs. This has discouraged many,” says Giri.

What is more concerning for Giri is that the government is not studying why medical students no longer want to become specialist doctors in the fields mentioned above.

“Students say they would not get jobs because the number of government positions is low. This is why the government should work on creating centres for certain disciplines of medical science,” says Giri.

The imbalance between time, investment and opportunity is one of the main reasons this is happening, say experts.

Becoming a general doctor takes around five and a half years. Doctors then study for three more years to get their post-graduate degrees. Even after that, a doctor has to spend another three years studying DM or MCH to become a superspecialist.

According to Prof Dr Anil Baral, a senior renal disease specialist at Bir Hospital, the government’s health system and the process of appointing doctors also determine whether medical students want to become specialist doctors.

According to Baral, doctors wanting to be nephrologists has decreased as they do not want to earn a modest income when they have to spend countless hours trying to become a nephrologist. Even after graduating, they still need to dedicate around three years to become specialists. What is worse is even then there are no job guarantees in the future.

“Why will doctors want to do this when they see no future? The private hospitals do not pay well. Government jobs are a rarity. Who would want to suffer knowing they would not get any return,” says Baral.

According to superspecialist doctors, there are some reasons for the lack of interest in studying specialist courses about diseases involving the heart, neurosurgery, kidney, and liver. They say that they have to study very hard and when graduated, they are overworked for very little pay. They also add that the job is risky; they do not get respect and do not have the option to join a private hospital after retiring from a government job.

Global or local problem?

Prof Dr Bhagawan Koirala, a senior heart surgeon working at Manmohan Cardiothoracic Vascular and Transplant Centre, says seating being vacant in complex medical fields is a global problem.

According to Koirala, students do not want to become specialists in heart surgery as it takes a long time to be able to perform surgery by oneself after acquiring the expertise. They also have to spend a long time in surgery and cannot give time to the family. On top of that, a lot of people die during heart surgery and many do not want to deal with the legal procedures and riots that take place due to that.

Some experts say many do not want to become superspecialist doctors because it is just not attractive enough given the lack of infrastructure and overall structure of health sectors in Nepal.

Koirala says that heart surgery is not attractive because there is less possibility to practise it at private hospitals. According to experts, after 2017, the situation is becoming critical in the study and production of heart surgeons in Nepal.

Comparing this situation with India and based on the population size, at least 90 heart surgeons should be working in Nepal to perform heart surgery. But, there are only 26 heart surgery specialist doctors in the country. What is concerning is the number of new students has been zero for two years.

According to Koirala, another reason is that Gangalal National Heart Center and Manmohan Cardiothoracic Vascular and Transplant Centre, which excel in heart surgery, have not advertised for jobs in recent days.

Prof Dr Rajeev Jha, a senior neurosurgeon at Bir Hospital, says that it is unfortunate that there is less interest in neurosurgery. According to the latest data, there are only 110 neurosurgeons in the country, almost all concentrated in the valley.

“There is a need for three times more surgeons,” says Jha.

Two decades ago, neurosurgery was an attractive field in medical science. Many went abroad to become neurosurgeons. According to Jha, this was because there was a lot of competition for government seats in Nepal. However, times have changed. Now, neurosurgery has not become a subject of interest due to the excessive work and lack of returns.

According to Jha, to become a neurosurgeon, a doctor needs two years of experience working in general surgery. After that, one has to study for three more years to get an MS degree. Even after that, to study neurosurgery, two more years of working experience in neurosurgery are required. After that, the MCH course should be done for three more years.

In this way, it takes about 10 to 11 years to become a neurosurgeon.

“In countries other than Nepal, one can become a neurosurgeon in less than a decade. It seems that the interest in this discipline has decreased due to the fact that they study for a long time,” says Jha.

As a neurosurgeon, a doctor has to work day and night. They rarely have a personal life, he says. “Therefore, many people are interested in other fields where the risk and stress are comparatively less and the earning is more,” says Jha.

Specialists on the brink

According to experts, if the government does not take measures to correct them, there may be a shortage of superspecialist doctors of various types within a few years.

This is a serious concern as the problems related to non-communicable diseases are increasing in recent years. According to the doctors involved in the treatment, one of the causes of non-communicable diseases is heart-related problems. Similarly, the burden of cancer, kidney problems, and tuberculosis is also increasing. With fewer specialist doctors in the country, people have to wait a long time to undergo surgeries.

As there are only a few doctors who specialise in kidney-related treatment, it has impacted service throughout the country as many have even died as they could not get their dialysis done on time.

“The current doctors will retire from the government service in a few years and as there is no production now, there will be an extreme shortage of doctors in the next few years,” says Baral.

Giving his own example, Baral says, “It takes three months to complete various checks when a patient gets a kidney transplant. Do I look after that one patient or 100 others who come to the OPD for treatment every day?”

More than 1,000 doctors are produced annually. But, not even 50 of them want to study to become superspecialists.

“The number of graduates in MBBS is very large, but there are few doctors who want to continue to study at the higher level,” says Baral.

So far 33 people have studied to become superspecialists in heart surgery in Nepal. One of them is currently studying in the country and one abroad. Out of 33 people, seven have left heart surgery and are going for vein and lung surgery.

But, according to Dr Raamesh Koirala, senior heart surgeon of Gangalal Hospital, around five to six superspecialist doctors who have returned from Bangladesh after training in heart surgery for five years are currently unemployed. The government has not created additional positions for them, and private hospitals cannot afford them.

Apart from pediatric heart disease and rheumatic heart disease, around 48,000 coronary artery bypass surgeries should be performed annually in Nepal. However, as of now, Nepal can only perform around 500 to 700.

Similarly, according to the Nepalese Society of Critical Care Medicine (NSCM), there are 26 specialist doctors in Nepal with DM in critical care medicine. However, most of them are forced to work in private hospitals due to a lack of vacancies in government-run hospitals.

Surprisingly, government hospitals do not have critical care units (CCUs) as they do not have specialists who can run them, says Prof Dr Subas Acharya, a critical care expert at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital.

According to NSCM standards, an ICU should be headed by a critical care physician. However, in government hospitals other than those in the Kathmandu valley, general surgeons, anesthesiologists and others are handling the responsibility of the ICU.

Neurosurgeon Prof Dr Rajeev Jha says neurosurgery is subject that puts a doctor under mental and physical stress, is more complicated and has an additional mortality rate, due to which neurosurgery has become less attractive.

Currently, only six doctors are working as neurosurgeons in the government service. Due to the lack of human resources, the number of patients in neurosurgery is high across the country.

“Looking at the number of patients here, there is a need for hundreds of neurosurgeons,” says Jha.

Similarly, liver disease specialist Dr Dilip Sharma also says that there is a need for 150 liver specialists in the country as per the current ratio of patients.

An all-time high need

The National Planning Commission formed a committee on June 9, 2022, to study the issue of producing human resources for the highly sensitive health sector, which is in short supply across the country. The committee’s findings have not been made public.

According to senior heart surgeon Bhagawan Koirala, arrangements should be made to prepare a five-year course in specialist services after MBBS to increase the number of specialist doctors needed for the country.

“After doing MS, the attraction of doing MCH is less. Therefore, the attractiveness of MS and MCH programs directly after MBBS will increase,” says Koirala.

Neurosurgeon Jha echoes Koirala’s statement. Stating that there is a five-year course directly after MBBS in other countries including India, he argues that a similar programme should be run in Nepal.

“Nowadays, only doctors who have done MS are able to do MCH. There will be no shortage of specialist doctors if the MCH-level course is taught directly after completing MBBS,” says Jha.

Former Health Secretary Dr Kiran Regmi says the lack of superspecialist doctors in government service is causing long-term damage to the health system.

According to public health expert Dr Kedar Baral, the government should make a long-term plan on how many doctors are needed to provide superspecialist services in the country.

“A plan should be prepared after assessing how much human resources the government needs and how much the market needs. After that every year, the number of seats should be fixed on the same basis,” says Baral.

Public health expert Dr Baburam Marasini says when the attraction of superspecialist doctors in some categories is low, there may be a compulsion to go to India and other countries for treatment in the coming days.

“The government should produce human resources for the superspecialist services. The health system cannot be improved if those who have studied at their own expense are not given job opportunities,” he says.

In the Nepal Health Account 2017 published by the Ministry of Health and Population, it is mentioned that as the state does not invest in specialist doctors, it is losing around Rs 2 billion annually. The report also says that about 17 per cent of citizens become poor due to receiving health services at high costs.

Former Health Secretary Dr Sainendra Raj Upreti fears that there may come a time when everyone might have to leave the country to get expert services.

“The government should make proper investment in the health sector as the number of patients with non-communicable diseases is increasing,” says Upreti.

Dr Krishna Prasad Paudel, head of the Policy and Planning Monitoring Division of the Ministry of Health and Population, says that there is a plan to increase human resources.

“If there are no human resources in any category, the government should create incentives to increase the attraction in such categories,” Paudel says.

This story was translated from the original Nepali version and edited for clarity and length.